Periodontal Disease

Includes: Gingivitis — Periodontitis — Periodontal Pockets

Introduction

Periodontal disease is essentially an inflammatory response by the supporting structures of the teeth known as the periodontium. These structures include the gingiva, periodontal ligaments, cementum and alveolar bone. It is the most common dental disease in dogs and cats and the major cause of tooth loss in both species. There are numerous factors that contribute to the formation of the disease but the primary agent is dental plaque. Plaque accumulates at the gingival margin, partly due to insufficient oral hygiene.

Periodontal disease is the result of the inflammatory response to dental plaque, i.e. oral bacteria, and is limited to the periodontium. It is probably the most common disease seen in small animal practice, with the great majority of dogs and cats over the age of 3 years having a degree of disease that warrants intervention.

Periodontal disease is a collective term for a number of plaque-induced inflammatory lesions that affect the periodontium. It is a unique infection in that it is not associated with a massive bacterial invasion of the tissues. Gingivitis is inflammation of the gingiva and is the earliest sign of disease. Individuals with untreated gingivitis may develop periodontitis. The inflammatory reactions in periodontitis result in destruction of the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone. The result of untreated periodontitis is ultimately exfoliation of the affected tooth. Thus, gingivitis is inflammation that is not associated with destruction (loss) of supporting tissue – it is reversible. In contrast, periodontitis is inflammation where the tooth has lost a variable degree of its support (attachment) – it is irreversible. Infection of the periodontium may cause discomfort to the affected animal. There is also strong evidence that a focus of infection in the oral cavity has been associated with disease of distant organs. Consequently, prevention and treatment of periodontal diseases is, contrary to common belief, not a cosmetic issue, but a general health and welfare issue.

Recent research into dog periodontitis has shown that the bacteria present in healthy canine mouths differ significantly from those found in healthy human mouths. Dogs lack significant numbers of streptococcal species which helps to explain why the incidence of Dental Caries is so much lower in dogs than humans. Instead, healthy canine plaque is dominated by aerobic gram negative bacteria including several Neisseria species along with Bergeyella zoohelcum and a canine Moraxella species. These differences between dog and human oral microbiology are important as they indicate that products or treatments developed for human oral care may not automatically be suitable for dog oral care. Treatments targeted at Streptococcus mutans are a case in point as we now know that dogs do not have this bacterium in their mouths. As periodontal disease progresses, the oral bacterial population shifts towards a more gram positive distribution with anaerobic species becoming more prevalent as the supply of oxygen is depleted, especially in periodontal pockets. Members of the genus Peptostreptococcae become much more prevalent, although the role of these bacteria is not yet known. Whether specific bacteria cause the onset of periodontitis has not yet been proven in either dog or human and it may be that the transition to the disease state might be facilitated by multiple different combinations of bacteria working together.

Dental calculus (tartar) forms when plaque is left undisturbed for a number of days. Calcium salts from saliva start to become deposited in the plaque causing it to harden and become resistant to removal. Diets high in minerals and diets consisting of soft rather than hard crunchy food exacerbate the problem. As dental plaque becomes calcified and the whole crown may become covered in brown chalky material. Calculus forms a brittle dirty brown covering to the tooth which may not affect the enamel at all but may produce mild gingivitis around the edge and the gum may start to recede. This exposes more of the crown, and may subsequently reach the level of the dentine and infection may enter the alveolus and loosen the ligaments holding tooth in and ultimately the tooth will become loose and fall out.

Gingivitis - Reversible inflammation of the marginal gingival tissues that does not affect the periodontal ligament or the alveolar bone.

Periodontitis - Inflammation and irreversible destruction of the tooth's supporting structures that includes the gingiva, periodontal ligament, alveolar bone and root cementum. It usually occurs after years of plaque accumulation and gingivitis. The epithelial attachments of the tooth regress apically and there is absorption of the associated alveolar bone, resulting in permanent loss of tooth support.

Periodontal pocket - this describes the area of tissue destruction left by periodontitis. It is an attachment loss due to destruction of the fibres and bone that support the tooth which results in a pathological deepening of the gingival sulcus.

Aetiology

The primary cause of gingivitis and periodontitis is accumulation of dental plaque on the tooth surface. Calculus (tartar) is only a secondary aetiological factor.

Dental plaque is a biofilm composed of aggregates of bacteria and their by-products, salivary components, oral debris, and occasional epithelial and inflammatory cells. Plaque accumulation starts within minutes on a clean tooth surface. The initial accumulation of plaque occurs supragingivally but will extend into the sulcus and populate the subgingival region if left undisturbed. The formation of plaque involves two processes, namely the initial adherence of bacteria and then the continued accumulation of bacteria due to a combination of bacterial multiplication and further aggregation of bacteria to those cells that are already attached.

As soon as a tooth becomes exposed to the oral cavity, its surfaces are covered by the pellicle (an amorphous coating of salivary proteins and glycoproteins). The pellicle alters the charge and free energy of the tooth surfaces, which increases the efficiency of bacterial adhesion. Certain specific bacteria can adhere directly to the pellicle. These have recently been shown to be mostly members of the genus Neisseria in dog plaque. These bacteria facilitate the recruitment of secondary bacterial species to the developing plaque biofilm. The plaque associated with healthy gingiva has a higher proportion of aerobic and facultative anaerobic bacteria. As gingivitis develops, plaque extends subgingivally. Aerobes consume oxygen and a low redox potential is created, which makes the environment more suitable for the growth of anaerobic species. The aerobic population does not decrease, but with increasing numbers of anaerobes, the aerobic/anaerobic ratio decreases. The subgingival florae associated with periodontitis are predominantly anaerobic bacteria.

Dental calculus (tartar) is mineralized plaque. However, a layer of plaque always covers calculus. Both supragingival and subgingival plaque becomes mineralized. Supragingival calculus per se does not exert an irritant effect on the gingival tissues. The main importance of calculus in periodontal disease seems to be its role as a plaque-retentive surface. This is supported by well-controlled animal and clinical studies that have shown that the removal of subgingival plaque on top of subgingival calculus will result in healing of periodontal lesions and the maintenance of healthy periodontal tissues.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenic mechanisms involved in periodontal disease include:

- Direct injury by plaque microorganisms

- Indirect injury by plaque microorganisms via inflammation

The microbiota in periodontal pockets is in a continual state of flux; periodontitis is a dynamic infection caused by a combination of bacterial vectors that change over time. As a result, the molecular events that trigger and sustain the inflammatory reactions constantly change. Many microbial products have little or no direct toxic effect on the host. However, they possess the potential to activate inflammatory reactions that cause the tissue damage. It is now well accepted that it is the host’s response to the plaque bacteria, rather than microbial virulence per se, that directly causes the tissue damage. In gingivitis, the plaque-induced inflammation is limited to the soft tissue of the gingiva. As periodontitis occurs, the inflammatory destruction of the coronal part of the periodontal ligament allows apical migration of the epithelial attachment and the formation of a pathological periodontal pocket (i.e. periodontal probing depths around the tooth increase). If the inflammatory disease is permitted to progress, the crestal portion of the alveolar process begins to resorb. Alveolar bone destruction type and extent are diagnosed radiographically.

Disease progression is generally an episodic occurrence rather than a continuous process. Tissue destruction occurs as acute bursts of disease activity followed by relatively quiescent periods. The acute burst is clinically characterized by rapid deepening of the periodontal pocket as periodontal ligament fibres and alveolar bone are destroyed by the inflammatory reactions. The quiescent phase is not associated with clinical or radiographic evidence of disease progression. However, complete healing does not occur during this quiescent phase, because subgingival plaque remains on the root surfaces and inflammation persists in the connective tissue. The inactive phase can last for extended periods. Other conditions, such as physical or psychological stress and malnutrition, may impair protective responses, such as the production of antioxidants and acute phase proteins, and can aggravate periodontitis, but do not actually cause destructive tissue inflammation.

A genetic predisposition to destructive inflammation of the periodontium may be important in some individuals.

Signalment

Pure bred cats are particularly susceptible and include: Burmese, Persian, Siamese and Maine Coon. The disease affects the majority of cats over two years of age.

Certain breeds of dogs are thought to be susceptible to an aggressive form of the disease and include: Greyhound and Maltese. Small breed dogs are more prone to periodontitis. This may be a result of tooth crowding predisposing the animal to the initiation and rapid progression of the disease.

Clinical Signs

Clinical signs include fetid breath odour (halitosis), excessive salivation, blood in saliva, dysphagia, pain on mastication and difficulty eating. There may also be loose teeth. The animal may be lethargic and show signs of weight loss and poor grooming (cats).

Diagnosis

An oral examination should be performed. This is the most important part of the diagnostic procedure and should include inspection of extraoral structures (looking for swelling, atrophy or asymmetry), such as face, lips, muscles of mastication, temporomandibular joints, salivary glands, lymph nodes, maxillae and mandibles. Intraoral structures such as the dentition, gingiva, mucosa, tongue, tonsils and dental occlusion should also be thoroughly examined. On visual inspection of the intraoral structures, an animal with periodontitis may demonstrate oral mucosal ulceration, inflammed and bleeding gingiva, loss of normal gingival contour, purulent discharge from the periodontal pocket, gingival recession, loose teeth and presence of variable quantities of plaque and calculus on the tooth surface.

Periodontal disease is associated with loss of the attachment apparatus of the tooth. Clinically this is hard to detect and there is no correlation between the amount of calculus seen on the tooth and the degree of destruction. Loss of attachment usually involves the periodontal ligament, bone, root cementum and gingiva. Clinically, mobile teeth may be evident and some teeth may have evidence of gingival recession and root exposure indicating that there is periodontal disease but for a full assessment, an examination has to be performed under general anaesthesia. A periodontal probe is used to assess the depth of the gingival sulcus and whether there is loss of bone or periodontal ligament. A probing depth greater than 3mm in most dogs would be considered abnormal. This does vary based on the tooth and the size of the dog. Any depth over 0.5mm in cats would be considered abnormal. The periodontal probe is used to assess the degree of gingivitis, measure the pocket depth, check whether the tooth is mobile, whether there is bone loss between the roots (furcation exposure) and measure the amount of gingival recession. The whole circumference of the tooth needs to be evaluated.

There are a number of methods that grade the severity of periodontal disease. It must be remembered though that different teeth in the mouth may be affected by different severities of the disease and even around each tooth, the degree of attachment loss may vary. Grading is based on the extent of attachment loss as this is indicative of periodontal destruction.

- Grade 0 = Healthy Gingiva

- Grade 1 = Established gingivitis

- Grade 2 = Mild periodontitis (<25% attachment loss based on radiographs)

- Grade 3 = Moderate periodontitis (25-50% attachment loss based on radiographs)

- Grade 4 = Severe periodontitis (>50% attachment loss)

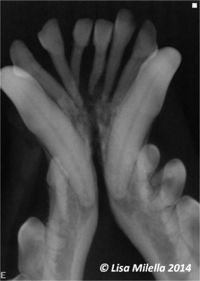

Oral radiography should be used to assess periodontal disease. Cases of periodontitis will show generalised horizontal and vertical alveolar bone loss in focal areas. Radiographic signs of periodontal disease include resorption/rounding of the alveolar margin, widening of the periodontal space, loss of the lamina dura (cortical bone of the alveolus) and alveolar bone destruction. Find more information about radiographic interpretation of periodontal disease.

Treatment

Treatment of periodontitis is two stage – periodontal therapy performed under general anaesthesia, and the most important stage is then follow up home care following an oral hygiene program.

Gingivitis

Treatment of gingivitis relies heavily on owner compliance. It is important to stress to the owner that the disease is reversible and treatment and control may prevent this disease from becoming peridontitis, which is a lot more severe.

The owner should receive information on good daily dental home care such as tooth brushing, diet and oral care chews.

Treatment involves performing a dental scale and polish and ensuring the owner is aware that regular examinations to assess the condition of the teeth will be required from now on.

Periodontitis

Educate the owner about the disease process and also on good daily dental home care such as tooth brushing, diet and oral care chews.

Perform a dental scale and polish and root surface debridement. Teeth with severe periodontitis will need to be extracted and periodontal surgery may be necessary.

Regular examinations to assess the condition of the teeth are vital and the owner needs to be made aware of this.

Periodontal Pockets

With pocket depths below 5mm, dental scaling and polishing should be performed, and then subgingival curettage and the placement of an antibiotic gel in the pocket may help rejuvenate the periodontal tissues and reduce pocket depth.

With pocket depths greater that 5mm, surgery is needed to either expose the root for treatment or extraction. Gingival flaps or bony replacement procedures for infrabony pockets can be used to decrease pocket depths in areas of alveolar bone loss.

| Periodontal Disease Learning Resources | |

|---|---|

To reach the Vetstream content, please select |

Canis, Felis, Lapis or Equis |

Test your knowledge using flashcard type questions |

Veterinary Dentistry Q&A 11 |

Selection of relevant videos |

Webinar:Oral homecare |

References

- Davis I, Wallis C, Deusch O, Colyer A, Milella L, Loman N and Harris S (2013). A cross-sectional survey of bacterial species in plaque from client owned dogs with healthy gingiva, gingivitis or mild periodontitis. PLOS ONE 8: e83158.

- Lobprise, H. (2007) Blackwell's five minute consult clinical companion: small animal dentistry Wiley-Blackwell

- Merck & Co (2008) The Merck Veterinary Manual Merial

- Tutt, C., Deeprose, J. and Crossley, D. (2007) BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Dentistry (3rd Edition) BSAVA

| This article was expert reviewed by Lisa Milella BVSc DipEVDC MRCVS. Date reviewed: 3 October 2014 |

| Endorsed by WALTHAM®, a leading authority in companion animal nutrition and wellbeing for over 50 years and the science institute for Mars Petcare. |

Error in widget FBRecommend: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt66299be597aa78_06685139 Error in widget google+: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt66299be59c40b6_58399795 Error in widget TwitterTweet: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt66299be59f6830_96925324

|

| WikiVet® Introduction - Help WikiVet - Report a Problem |