Coccidiosis - Poultry

Introduction

Coccidiosis is a disease of poultry which is of worldwide importance, both economically and for animal welfare reasons. It is a disease of over-crowding and poor hygiene, hence it is prevalent in intensive chicken farming globally, however, it can affect birds in any facilities. Although outbreaks of the disease are not common, coccidia remains in most flocks as a subclinical disease, which in times of stress can establish into a clinical disease. Many commercial units now use prophylactic drugs in order to try to control the disease.

Domestic poultry and birds are affected by coccidia called Eimeria. Different species of Eimeria that effect poultry are host-specific – meaning that a species that infects chickens does not infect turkeys and vice versa.

Nine species of Eimeria infect chickens. The most important species in broiler production include Eimeria tenella (90%), E. maxima, E. acervulina, and E. mivati; the species important in breeder and egg-layers are E. burnetti and E. necatrix. There are 4 malabsorptive species, which range from low to moderate pathogenicity and 3 haemorrhagic species, which are all highly pathogenic. All seven species have different predilection sites in the alimentary system and cause unique pathological changes.

Seven species infect turkeys – the big three of concern are Eimeria meleagrimitis, E. adenoeides, and E. gallapovonis.

Currently 13 species of coccidia have been reported in ducks but only certain species have been researched. Eimeria, Wenyonella or Tyzzeria genuses are found in wild and farmed birds.

There are three main species of coccidia in pheasants, all three of which fall into the Eimeria genus.

In Geese, there are two strains Eimeria truncata and E. anseris, which are of most pathogenic importance, with the latter causing intestinal disease and E. truncata causing renal coccidiosis.

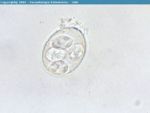

Coccidia have a direct life cycle, with a one week prepatent period. After oocysts are ingested, sporozoites are released which penetrate the intestinal epithelium and 2 asexual phases of multiplication called schizogony occur followed by a phase of sexual multiplication called gametogony. The zygote develops into an oocyst which is then shed in the faeces. An oocyst measures around 20-30μm and for each oocyst ingested, thousands are shed. The life cycle is self-limiting and organisms from a single infection go through the sequence of developmental stages synchronously. Organisms leave the body simultaneously as oocysts. Oocysts are only infective once they have sporulated and sporulation requires warmth, moisture and oxygen; this will take around 2-3 days in broiler houses.

Epidemiology

Oocysts are ubiquitous and robust and can survive several months to several years in the environment, meaning it is almost impossible to keep buildings free from infection. Even with strong disinfection after every batch has gone, the new chicks will become infected by pecking the ground shortly after being placed in the poultry house.

The biotic potential is enormous and generation time is short, meaning infections can build up rapidly. Immunity however, develops slowly and certain species of Eimeria will inflict a faster immune response and longer lasting immunity than others.

Clinical Signs

Depends on the pathogenicity of the coccidia involved and the concurrent health status of the chicken.

In most poultry animals, severe enteritis is the main clinical symptom. Haemorrhagic diarrhoea is seen with the most pathological strains of the disease along with mucoid discharge. Weight loss, general malaise, reduced appetite and depression are other common signs. Sudden death can occur, often in younger birds. Morbidity is usually very high but mortality is variable. In geese, renal coccidiosis can occur and signs include severe depression such as reduced appetite and huddling, emaciation and diarrhoea. Mortality rates are high, however, birds that recover from the infection remain strongly resistant to it for life.

Diagnosis

Clinical signs and history are usually enough to make a presumptive diagnosis. However, as clinical signs can vary, the most useful diagnostic tool is a necropsy on a recently dead bird that has been sacrificed for this purpose. A bird that has died naturally and has been dead for over one hour will make post mortem examination difficult due to post mortem changes in the intestinal mucosa. Observation of caseous core lesions in the caecum and sloughing of the intestinal walls will strengthen a presumptive diagnosis. A sample of mucosa should be taken for examination under the microscope in order to identify oocysts, which will confirm the diagnosis. Specific identification of genus of coccidia is not required as treatment is the same for all.

The presence of coccidia and mild lesions are present in most young birds between the age of 3 - 6 weeks of age but do not mean the bird has clinical coccidiosis. The severity of the lesions should determine a diagnosis of coccidiosis being made.

Lesions and their location vary depending on which Eimeria genus is causing the disease:

- Eimeria acervulina: proximal gut, thickened walls, 'white ladder lesions' produced by dense foci of gamonts and oocysts and a watery exudate are likely to be found in this case.

- Eimeria maxima: mid-gut, thickened walls and a pink exudate with this coccidia.

- Eimeria tenella: swollen caeca, thickened intestinal walls, dark colouring of damaged intestine containing a core of necrotic tissue and blood.

- Eimeria necatrix: mid-gut, the wall will show 'ballooning', white spots and petechiae form characteristic 'salt and pepper' lesions and there will be haemorrhage into the lumen.

As well is post mortem examination of gross lesions, scrapings of the mucosa should be taken for examination under the microscope. The number of oocysts should be counted and examined for shape and size to aid identification.

Treatment and Control

Control is dependent on hygiene and good husbandry, such as disinfection of housing and good ventilation. It is important to prevent wild birds entering the housing or defaecating in the housing as this is a common cause of spread of the disease.

If an outbreak does occur, treatment is usually with sulphonamides. Other anit-coccidial drugs have varying degrees of safety and efficacy in different poultry species.

Prevention of this disease is much more valuable than treatment should an outbreak occur. In commercial poultry farms, many measures are undertaken to control the disease. Intensive poultry production is largely dependent on the use of anticoccidial drugs, as well as strict hygiene controls.

For more information see antiprotozoal drugs.

Layers:

[Vaccines|Vaccines]] are used for laying hens as these have a longer life span than broilers so will develop an immunity. Paracox 7 vaccine is a multivalent attenuated live vaccine for replacement layers, which contains 7 live strains of Eimeria. These live strains lack the most pathogenic life cycle stage making the prepatent period shorter. These are known as precocious strains.

Chicks are vaccinated on a single occasion when they are 1-9 days old through oocyst suspension in the feed or water. For a short period, vaccinated birds have sub-optimal growth rates so this is why they are not used for broilers.

Broilers:

As broilers have a much shorted life span than laying hens, vaccination is not the most economical option in this case.

The continuous use of a single anti-coccidial drug from day one of life through to slaughter is used. As the broiler does not live for long, immunity would not have time to develop so providing anti-coccidial drugs on a constant basis controls the disease well.

Some producers will use the 'dual' or 'shuttle' method, which follows the same basis of using anti-coccidials constantly, but two or three different drugs are given throughout the chickens' life; e.g. one drug in the starter, a different one in the grower and another in the finisher. This is thought to control coccidia more efficiently as it will reduce the resistance build up to one drug.

A vaccine called Paracox 5, which contains 5 strains of the most pathogenic Eimeria can be used for broilers. It is sprayed onto the first feed offered to new batches of chicks and will provide integrated control. Careful management throughout is required so in-feed prophylaxis and vaccination do not fail.

Strict hygiene measures in both layers and broilers is needed to control coccidia. Litter should be removed and the housing thoroughly disinfected between crops. The ideal turnaround should be no less than 10 days, but this often is impracticable for economic reasons. Over-crowding exacerbates coccidiosis, so the lowest stocking density which is compatible with economic production should be used.

Water bowls, roofs and walls should be well maintained to prevent litter becoming damp and stress factors should be avoided and adequate nutrition provided.

Should an outbreak occur, treatment with anti-coccidial drugs, such as sulphonamides, diclazuril, decoquinate and monensin should be administered into the drinking water with immediate effect. The farm's control measures should then be examined and reviewed.

| Coccidiosis - Poultry Learning Resources | |

|---|---|

Test your knowledge using flashcard type questions |

Coccidia Flashcards |

Selection of relevant videos |

Chicken Caeca Infected with Eimeria tenella potcast |

Full text articles available from CAB Abstract (CABI log in required) |

Coccidiosis in poultry: review on diagnosis, control, prevention and interaction with overall gut health. Gussem, M. de; World's Poultry Science Association (WPSA), Beekbergen, Netherlands, World Poultry Science Association, Proceedings of the 16th European Symposium on Poultry Nutrition, Strasbourg, France, 26-30 August, 2007, 2007, pp 253-261, 36 ref. |

References

Fox, M and Jacobs, D. (2007) Parasitology Study Guide Part 1: Ectoparasites Royal Veterinary College

Merck & Co (2008) The Merck Veterinary Manual (Eighth Edition) Merial

Jordan, F, Pattison, M, Alexander, D, Faragher, T, (1999) Poultry Diesease (Fifth edition) W.B. Saunders

Randell, C.J, (1985) Disease of the Domestic Fowl and Turkey, Wolfe Medical Publication Ltd

Saif, Y.M, (2008) Disease of Poultry (Twelfth edition) Blackwell Publishing

| This article has been peer reviewed but is awaiting expert review. If you would like to help with this, please see more information about expert reviewing. |

Error in widget FBRecommend: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt6620f2d24edc08_75760230 Error in widget google+: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt6620f2d2588a91_40292486 Error in widget TwitterTweet: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt6620f2d25eed40_88533706

|

| WikiVet® Introduction - Help WikiVet - Report a Problem |