Endocarditis

Introduction

Endocarditis is defined as an inflammation of the cardiac endocardium. The infection can affect the valves (valvular endocarditis) and then spread to the heart wall (mural endocarditis). It is usually a result of a bacteraemia or pyaemia, spread from adjacent myocardium is rare. It occurs in all species and is more common in cattle, pigs and sheep than dogs and cats.

Organisms commonly isolated include:

- Cattle: Actinomyces pyogenes

- Pigs: Erysipelothrix spp.

- Sheep: Streptococci

- Dogs: Streptococci, Staphylococci and E. coli

Pathophysiology

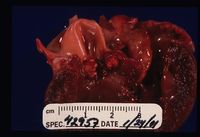

Vegetative Endocarditis

It is predisposed by valvular damage as thrombi occur on the surface of the valves exposed to blood flow. Mechanical trauma can cause such damage, such as jet lesions from turbulent blood flow or endocardial injury from a catheter extending into the heart. Highly virulent bacteria or a heavy bacterial load increase the risk of cardiac infection, and normal valves can be invaded by virulent bacteria. Bacteremia is essential for the development of endocarditis. Diseases that impair immune responses or cause hypercoagulability or endothelial disruption are thought to increase the endocarditis risk. Once bacteria colonise the valvular endocardium, vegetative lesions composed of platelets and fibrin are formed on the valves. Progression to rupture of the chordae tendinae is possible, along with spread of the infection to the adjacent mural endocardium. Valves may become stenotic, incompetent or both. Congestive heart failure commonly results from valvular insufficiency and volume overload. Because the mitral and aortic valves are typically affected, pulmonary oedema is the usual manifestation. Death usually results from either embolisation of the vegetative material or congestive heart failure due to significant valvular damage. Metastatic infection of other body sites commonly occurs.

Ulcerative Endocarditis

Commonly seen along with renal failure in dogs. Uraemia irritates and damages the endocarium, particularly in the left atrium. Oedema is seen in the subendocardial tissue with deposition of glycosaminoglycans. This may progress to a necrotising endocarditis and, in extreme cases, left atrial rupture. If renal sufficiency is re-established then healing of the endocardial lesion is possible.

Species differences

Cattle: the disease predominantly affects the tricuspid valve, perhaps due to bacteria arising in the GI tract and liver. Common underlying causes include liver abscesses, traumatic reticulitis, metritis, mastitis, navel abscesses and 'joint ill'. Congestive right sided failure is manifested as ascites (including bottle jaw) and embolisation to the lungs. Anaemia is often present as the red blood cells are damaged as they pass through the vegetation.

Horse: Lesions occur mainly on the mitral valve. The site of sepsis is often not identified but may be a sequale to septic jugular thrombophlembitis.

Pig and Dog: Lesions occur particularly on the mitral valve (71% of cases in dogs), perhaps due to the higher pressure blood flow on the left side of the heart leading to more valvular damage. Left sided heart failure and pulmonary oedema are seen clinically, as are emboli in various organs, particularly the kidney.

Signalment

Endocarditis is rare in dogs but males and large breeds (e.g. German Shepherds) are most affected. Dogs with subaortic stenosis are more at risk of developing the disease. It is very rare in cats. The disease mainly affects adult cattle and young pigs. In horses, males are more commonly affected than females.

History & Clinical Signs

Clinical signs are often vague and rarely referable to congestive heart failure. The following clinical signs are seen related to sepsis:

- Pyrexia

- Lameness

- Neck Pain

- Lethargy/Anorexia

- Weight loss

- Epistaxis

Signs of embolisation to other organs may also be seen and those of congestive heart failure (dyspnoea, poor pulses, pale mucous membranes, tacchycardia, pulmonary crackles)

Physical examination

A variable murmur depending upon the valve affected. It may be noted that murmur has recently arisen or changed. Other clinical examination findings include joint effusions, lymphadenopathy, pyrexia and in advanced cases signs associated with disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (D.I.C) such as bleeding diathesis and petechiation.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis can be difficult but a presumptive diagnosis is made on two or more positive blood cultures in addition to either echocardiographic evidence of vegetations or valve destruction, or the documented recent onset of a regurgitant murmur.

Laboratory findings

Blood profiles: Not all cases will have altered blood changes. Possible changes include:

- Haematology - Neutrophilia, left shift, monocytosis, thrombocytopaenia and prolonged clotting times if developing D.I.C.

- Biochemistry - Hypoalbuminaemia and hypoglycaemia.

Urinalysis : may have proteinuria, casts, pyuria. A urinary tract infection may be present with the same organism as is responsible for the endocarditis.

Blood cultures : Requires 3-4 sterile samples collected from the jugular vein at least 1 hour apart over a 24 hour period. Negative cultures do not rule out the possibility of bacterial endocarditis.

Echocardiography

Structural abnormalities and vegetations may be visible on the valves although it is difficult to differentiate from endocardiosis.

Radiography

Radiography is often unremarkable. There may be evidence of cardiomegaly or congestive heart failure if valvular damage is chronic or severe. Evidence of a focus of infection such as discospondylitis may be visible.

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

ECG may be normal. Arrhythmias detectected are often ventricular in origin (e.g. ventricular premature complexes) and represent extension of the inflammatory focus to involve the myocardium. 3rd degree heart block may be present if the AV node is affected.

Treatment

Antibiotic treatment with either a broad spectrum antibiotic or an appropriate antibiotic based on culture and sensitivity results. Antibiotics should be administered intravenously for the first 5 days of therapy followed by a prolonged course (>4 weeks) of oral medication.

Common Protocols use Ampicillin in combination with a Fluoroquinolone such as Enrofloxacin or an aminoglycoside.

Secondary problems such as septic shock, D.I.C., congestive heart failure and embolisation need to be managed. Treatments commonly include diuretics or vasodilators to control the oedema, reduce valvular regurgitation and improve cardiac output.

Prognosis

Long term prognosis is guarded to poor. Possible complications include septic shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, congestive heart failure and embolisation to other organs.

| Endocarditis Learning Resources | |

|---|---|

Test your knowledge using flashcard type questions |

Small Animal Emergency and Critical Care Medicine Q&A 01 |

Search for recent publications via CAB Abstract (CABI log in required) |

Endocarditis publications |

References

Merck & Co (2008) The Merck Veterinary Manual (Eighth Edition) Merial

Nelson, R.W. and Couto, C.G. (2009) Small Animal Internal Medicine (Fourth Edition) Mosby Elsevier.

Tilley,L.P., Smith, F.W.K, Oyama, M., Sleeper, M. (2007) Manual of Canine and Feline Cardiology Saunders.

Elwood, C.M., Cobb, M.A., Stepien, R.L., (1993) Clinical and echocardiographic findings in 10 dogs with vegetative bacteria endcarditis. Journal of small animal practice. 34, pp420-427.

| This article has been peer reviewed but is awaiting expert review. If you would like to help with this, please see more information about expert reviewing. |

Webinars

Failed to load RSS feed from https://www.thewebinarvet.com/cardiology/webinars/feed: Error parsing XML for RSS