Behavioural Consultation and History Taking

Introduction

The majority of behavioural cases presented in veterinary practice are related to normal feline behaviour that is expressed in an inappropriate or undesirable manner.

Physical health

It is important to be aware that health problems are a common causal or underlying factor in behavioural problems in cats. For example, lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) and housesoiling and indoor urine marking are commonly linked. A full physical and clinical examination should be completed before any type of behavioural therapy is implemented. Behavioural changes may precede clinical signs, and also persist after an illness is apparently resolved.

The main ways in which health problems can affect behaviour include:

- Altered motivation: Polyphagia and polydipsia (e.g. due to diabetes mellitus or hyperthyroidism) can lead to competition over resources, pain can cause increased defensive behaviour

- Altered perception or cognition: Decreased awareness of signalling can lead to interact conflict (e.g. visual impairment), and cognitive dysfunction can lead to confusion, anxiety and irritability. Focal epilepsy can produce confusion, sensory disturbances and mood changes.

- General response to illness: Inflammatory cytokines activate a pattern of decreased activity, social withdrawal and avoidance that is called sickness behaviour (due to the effect of inflammatory cystokines).

Additionally, high levels of stress can cause alterations in behavioural, physiological and immune responses. Stress-linked alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary axis may be linked to effects on levels of dopamine, serotonin, noradrenaline and prolactin. In animals, stress is a contributing factor to gastrointestinal disturbances, skin conditions, feline interstitial cystitis as well as compulsive disorders and increased fear responses.

History Taking

Detailed history taking is the most important aspect of reaching a diagnosis in behavioural medicine. This should include information about:

- The problem from the client's perspective and their expectations of treatment.

- Individual cats (origin, development, influential experiences, personality traits, history of sociability with other cats and people, current and past health, current and past drug treatments).

- The physical environment (including resource availability and distribution, opportunities to perform normal behaviour and avoidance and escape responses).

- Important changes; for example the introduction of a cat, arrival of a new baby, house move, building work, or a change of owner employment/health.

- The social environment (relationship with other resident cats, people and other animals).

- The relationship with the owner.

- Methods of treatment already used by the owner (including punishment)

- The owner's level of knowledge of normal cat behaviour

- Detailed description of specific events (including context, triggering events/stimuli, and the individual's response).

It is also often helpful to place key information onto a timeline, as this can make it easier to visualise the connnection between events in the cat's life.

Prognosis is considerably affected by owner expectation; it may not be possible to achieve complete harmony between a group of cats, but if this is the only acceptable outcome for an owner then the prognosis will be poor.

Historical information and observation may be supplemented with videos or visits to the animals normal environment.

Social Structure within the Home

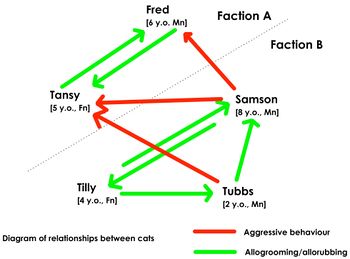

If more than one cat resides within the same home, it is important to establish their relationship. An interaction, similar to the one in the figure 1., can be used to show the pattern of interaction between cats. During the consultation, the clinician questions the owner about a range of affiliative and aggressive behaviours, and annotates the diagram.

- Friendly: e.g. grooming, rubbing against, tail-up greeting

- Aggressive: e.g. chasing, growling, hissing, spitting, fighting

It is possible to have no affiliative behaviour at all between members of a group of cats, or a to find that there is a a cohesive group with single outsider. Factions are also often found to exist with a household. Understanding the social relationships between cats provides a basis for resource distribution, reduce inter-cat conflict and and finding ways to re-integrate the group.

Resource availability and distribution

The correct distribution and availability of resources is critical to preventing and treating inter-cat conflict. Information should be collected that enables the clinician to identify sources of stress, such as competition for food.

House Layout

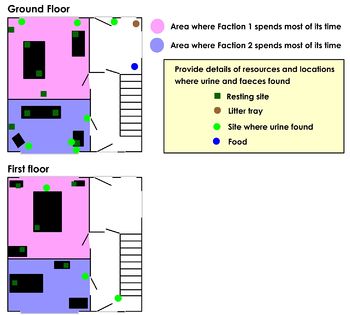

Draw a diagram of the house to show where the cats have food, water, litter trays and cat flap (similar to the figure 2. image). Also mark on this where urine or faeces have been found and which cat left them, if relevant. This is particularly important in cases of housesoiling but is useful in other cases too as it helps to establish the appropriate allocation of resources. This layout can be supplemented with images.

Feeding

Food is the resource that is at the centre of most conflict between resident cats.

- Food type (wet, dry etc)

- Access type (ad-lib, meal fed, on demand, simulated foraging)

- Number of locations

The preference is for ad-lib access in more than one location with food being available at all times, ideally using simulated foraging (activity feeding).

Latrine sites

Cat show strong latrine preferences, and information should be collected to identify any problems with latrine provision:

- Litter type.

- Litter depth.

- Type of tray (size, covered/uncovered).

- Location (and level of privacy afforded by this locate).

- Number of litter trays.

- Presence of latrine locations in the garden.

The preference is for mineral based, unscented litter filled to a depth of 2-3cm. Facies should be removed daily, along with significant urine contamination. Separate latrines should be provided for urine and faeces, and the formula generally quoted for the optimum number of trays is 1 per cat plus 1. Latrines should be in locations that offer the cat privacy, and should be well away from feeding and resting areas.

Environmental quality

Cats need opportunities to perform normal behaviours, and to be able to avoid, or withdraw from, social contact. This means that owners should provide opportunities for play, climbing and resting in the home. The requirement for a stimulating environment is increased if cats do not have outdoor access.

The outdoor environment should provide opportunities to explore, leave scent marks, hide shelter. It should also provide latrine sites and be planted to provide cover for the cat whilst moving around the garden (shrubs, tree etc). Gardens that encourage insects are also likely to be more stimulating for cats, since insects form part of the cat's diet and are a potential hunting stimulus.

Outdoor Access

- Access level/frequency: none, free access, permissive, on demand, etc.

- Access type: e.g. cat door, window.

- Access security: e.g. insecure cat floor, security coded cat door.

The preference is for free access Information about access to the outdoors also plays a vital part of a feline behavioural consultation. The main question is whether the cat has any outdoor access at all, then to what extent and whether it can control its own access. The questions asked should be similar to: Can the cats go outdoors? Does the owner have to let them in and out? Is there a cat flap? If so, is it open at all times? Is it an electronic/magnetic coded one? Do the cats have other ways in and out of the house [windows etc]? Are any of the cats reluctant to go out? Is there a reason the owner is aware of why they won’t go out? Do any of the cats go to the toilet in the garden?

More detailed information is then obtained depending on the main problem:

References

- Heath, S. Chapter 5, Common Feline Behavioural Problems – Feline Medicine and Therapeutics. 2004 British Small Animal Veterinary Association.

- Merck Veterinary Manual (10th Edition) - Behaviour. 2011 The Merck Publishing Group.

| This article is still under construction. |