Difference between revisions of "Pulpy Kidney"

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

Enterotoxaemia due to ''Clostridium perfringens'' type B causes severe enteritis and dysentery with a high mortality in young lambs (lamb dysentery), but also affects calves, pigs, and foals. The β toxin it produces is highly necrotising and is responsible for severe intestinal damage. ε toxin also plays a part in pathogenesis. The incidence of lamb dysentery declined over the past 20 years or so, due to the widespread use of clostridial vaccines<sup>3</sup>, but the condition is now becoming a problem again as complacency reduces the use of vaccination. Outbreaks of lamb dysentery typically occur during cold, wet lambing periods when lambing ewes are confined to small areas of shelter which rapidly become unhygienic. Most cases are seen in stronger, single lambs<sup>3</sup> because these animals consume the largest quantities of milk, which functions as a growth medium for ''C. perfringens''. | Enterotoxaemia due to ''Clostridium perfringens'' type B causes severe enteritis and dysentery with a high mortality in young lambs (lamb dysentery), but also affects calves, pigs, and foals. The β toxin it produces is highly necrotising and is responsible for severe intestinal damage. ε toxin also plays a part in pathogenesis. The incidence of lamb dysentery declined over the past 20 years or so, due to the widespread use of clostridial vaccines<sup>3</sup>, but the condition is now becoming a problem again as complacency reduces the use of vaccination. Outbreaks of lamb dysentery typically occur during cold, wet lambing periods when lambing ewes are confined to small areas of shelter which rapidly become unhygienic. Most cases are seen in stronger, single lambs<sup>3</sup> because these animals consume the largest quantities of milk, which functions as a growth medium for ''C. perfringens''. | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | Pulpy kidney disease, which is caused by C perfringens | ||

| + | type D, is by far the commonest of the enterotoxaemias. | ||

| + | It is usually encountered in growing lambs of four to 10 | ||

| + | weeks of age, and in finishing lambs of six months of | ||

| + | age and above. However, it is not unusual for adults to | ||

| + | be sporadically affected. Rams, in particular, appear to | ||

| + | be susceptible when they are on a rising plane of nutrition | ||

| + | in preparation for mating. | ||

| + | C perfringens elaborates a non-toxic protoxin, which | ||

| + | is converted to the lethal epsilon toxin by the action of | ||

| + | Very congested small intestine and ecchymosal | ||

| + | haemorrhages on the abomasum of a three-month-old lamb | ||

| + | with acute pulpy kidney disease (Picture, Shrewsbury VIC) | ||

| + | Congested small intestine in | ||

| + | a lamb under 14 days of age | ||

| + | with lamb dysentery | ||

| + | (Picture, Carmarthen VIC) | ||

| + | trypsin. The disease is peracute and the majority of cases | ||

| + | are found dead. In the rare instances that animals survive | ||

| + | for a short time, diarrhoea is a feature, as are CNS signs | ||

| + | due to the development of focal symmetrical encephalomalacia; | ||

| + | typcially, there is ataxia, progressing to | ||

| + | recumbency, opisthotonos, convulsions with or without | ||

| + | nystagmus, and death. | ||

| + | |||

Clostridium perfringens type D causes enterotoxemia in small ruminants of all ages; [1,10] disease in cattle appears to be very rare [27]. Clostridium perfringens type D is not considered to be a common inhabitant of the gastrointestinal tract of normal ruminants, although it can be carried sporadically by healthy animals [10]. As for type C enterotoxemia, passage of soluble carbohydrates or protein into the small intestine is thought to induce rapid replication and elaboration of epsilon toxin from this organism [24]. Unlike beta toxin, however, epsilon toxin is activated by intestinal and pancreatic proteases [1]. Once absorbed into the bloodstream, epsilon toxin causes loss of endothelial integrity, increased capillary permeability, and edema formation in multiple tissues [28]. | Clostridium perfringens type D causes enterotoxemia in small ruminants of all ages; [1,10] disease in cattle appears to be very rare [27]. Clostridium perfringens type D is not considered to be a common inhabitant of the gastrointestinal tract of normal ruminants, although it can be carried sporadically by healthy animals [10]. As for type C enterotoxemia, passage of soluble carbohydrates or protein into the small intestine is thought to induce rapid replication and elaboration of epsilon toxin from this organism [24]. Unlike beta toxin, however, epsilon toxin is activated by intestinal and pancreatic proteases [1]. Once absorbed into the bloodstream, epsilon toxin causes loss of endothelial integrity, increased capillary permeability, and edema formation in multiple tissues [28]. | ||

Revision as of 19:57, 24 August 2010

| This article is still under construction. |

Description

Lamb dysentery is a peracute and fatal enterotoxaemia of young lambs caused by the beta and epsilon toxins of Clostridium perfringens type B. C. perfringens is a large, gram positive, anaerobic bacillus that is ubiquitous in the environment and commensalises the gastrointestinal tract of most mammals1. Five genotypes of Clostridium perfringens exist, named A-E, and all genotypes produce potent exotoxins. There are 12 exotoxins in total, some of which are lethal and others which are of minor significance2. These are produced as pro-toxins, and are converted to their toxic froms by digestive enzymes. The enterotoxaemias are a group of diseases caused by proliferation of C. perfringens in the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract and excessive production of exotoxin.

In healthy animals, there is a balance between multiplication of Clostridium perfringens and its passage in the faeces. This ensures that infection is maintained at a low level. However, C. perfringens is saccharolytic and is therefore able to multiply rapidly when large quantities of fermentable carbohydrate are introduced to the anaerobic conditions of the abomasum and small intestine, leading to build-up of exotoxin. Gut statis, for example due to insufficient dietray fibre or a high gastrointestinal parasite burden, can also contribute to the accumulation of toxins.

Enterotoxaemia due to Clostridium perfringens type B causes severe enteritis and dysentery with a high mortality in young lambs (lamb dysentery), but also affects calves, pigs, and foals. The β toxin it produces is highly necrotising and is responsible for severe intestinal damage. ε toxin also plays a part in pathogenesis. The incidence of lamb dysentery declined over the past 20 years or so, due to the widespread use of clostridial vaccines3, but the condition is now becoming a problem again as complacency reduces the use of vaccination. Outbreaks of lamb dysentery typically occur during cold, wet lambing periods when lambing ewes are confined to small areas of shelter which rapidly become unhygienic. Most cases are seen in stronger, single lambs3 because these animals consume the largest quantities of milk, which functions as a growth medium for C. perfringens.

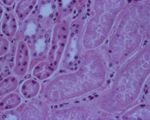

Pulpy kidney disease, which is caused by C perfringens type D, is by far the commonest of the enterotoxaemias. It is usually encountered in growing lambs of four to 10 weeks of age, and in finishing lambs of six months of age and above. However, it is not unusual for adults to be sporadically affected. Rams, in particular, appear to be susceptible when they are on a rising plane of nutrition in preparation for mating. C perfringens elaborates a non-toxic protoxin, which is converted to the lethal epsilon toxin by the action of Very congested small intestine and ecchymosal haemorrhages on the abomasum of a three-month-old lamb with acute pulpy kidney disease (Picture, Shrewsbury VIC) Congested small intestine in a lamb under 14 days of age with lamb dysentery (Picture, Carmarthen VIC) trypsin. The disease is peracute and the majority of cases are found dead. In the rare instances that animals survive for a short time, diarrhoea is a feature, as are CNS signs due to the development of focal symmetrical encephalomalacia; typcially, there is ataxia, progressing to recumbency, opisthotonos, convulsions with or without nystagmus, and death.

Clostridium perfringens type D causes enterotoxemia in small ruminants of all ages; [1,10] disease in cattle appears to be very rare [27]. Clostridium perfringens type D is not considered to be a common inhabitant of the gastrointestinal tract of normal ruminants, although it can be carried sporadically by healthy animals [10]. As for type C enterotoxemia, passage of soluble carbohydrates or protein into the small intestine is thought to induce rapid replication and elaboration of epsilon toxin from this organism [24]. Unlike beta toxin, however, epsilon toxin is activated by intestinal and pancreatic proteases [1]. Once absorbed into the bloodstream, epsilon toxin causes loss of endothelial integrity, increased capillary permeability, and edema formation in multiple tissues [28].

Type D enterotoxemia in sheep is typically a peracute illness, with many cases simply being found dead. If a live ovine case is detected, neurologic signs predominate. Lethargy and ataxia are evident early on, with collapse, hyperesthesia, lateral recumbency, convulsive paddling, and opisthotonus following within hours. Diarrhea is inconsistently seen. Glucosuria is frequently present [29].

- Pulpy kidney disease in well-fed 3-10 week-old lambs

- Caused by Clostridium perfringens type D

- Follows overeating high grain diet or luchious pasture

- Starch from partially digested food enterering the intestine from the rumen allows rapid clostridial proliferation

- Epsilon toxin activated by proteolytic enzymes causes toxaemia

- Epsilon toxin increases intestinal and capillary permeability; also alpha toxin

- Lambs found dead or with opisthotonos, convulsions, coma in acute phases

- Blindness and head pressing in subacute disease; bloat in later stages

- Hyperglycaemia, glycosuria

- Post mortem: hyperaemia in intestine; fluid in pericardial sac; kidney autolysis with pulpy cortical softening (acute death)

- Subacute death causes symmetrical encephalomalacia and haemorrhage in basal ganglia and midbrain

- Enterotoxaemia in kids and adult goats

Signalment

Diagnosis

- Location of the organism in the gut contents is not helpful, since it is always present (as a commensal).

- Therefore, diagnosis is by location of the toxin in the gut contents.

- Toxin is tested for by administering filtered intestinal fluid intravenously to a mouse (mouse protection test).

- If the toxin is present, the mouse should die within minutes or hours.

- Another mouse can be protected from the effect of the toxin with a specific antibody.

- An ELISA test is also possible.

- However, an ELISA is often too sensitive as the toxin can be present in the normal sheep gut and the ELISA can pick this up.

Clinical Signs

The time course from onset to death is only a few hours, so sheep are normally found dead and only occasionally seen alive.

- Nervous signs, such as head pressing, may be seen.

- Paralysis of the oesophagus may result in severe bloat.

- Profuse greenish diarrhoea is seen occasionally just before death.

- Only mild catarrhal enteritis is seen in the gut.

Laboratory Tests

Pathology

At necropsy examination, the peritoneal, pleural, and / or pericardial spaces are filled with variable volumes of straw- or red-colored fluid that may contain fibrin clots. Petechial hemorrhages are often visible on the visceral surfaces. Pulmonary and mesenteric edema may be evident. Gross lesions of the intestinal tract are frequently absent in affected sheep. Dipstick analysis of urine collected from the bladder frequently reveals the presence of glucose. The renal cortex may be softened (hence the term "pulpy kidney"), although this is a nonspecific autolytic change seen on occasion in small ruminant cadavers. The thalamus and cerebellum may be appreciably soft, with scattered hemorrhages therein. Occasionally, no gross lesions are seen in ovine cases of type D enterotoxemia [24].

- Animals are very bloated.

- Often lack lesions.

- Guts appear slightly flaccid, and a bit hyperaemic.

- The toxaemic carcase has petechial and echymotic haemorrhages, and hydropericardium.

- The kidneys are characteristically affected.

- Become oedematous, mushy and red within about 1 hour of death.

- A stream of water on cut surface of the kidney washes away the epithelium (since it is necrotic) and leaves fronds of tissue (This is the case with any kidney if the post mortem is more than a few hours after death).

- This accelerated post mortem change is a characteristic of the disease.

- Glycosuria is a feature

- The toxin affects the epithelium of the proximal part of nephron, stopping resorption of glucose.

- Note: the swelling of cells in the kidney means that anuria occurs, meaning there is no urine avaialable to rest for glucose.

- It is sometimes possible to get a positive reaction to a stick test by wiping it on the inside of the bladder.

- Periportal hepatic fatty change occurs.

- This is only really seen histologically.

- Grossly, the liver looks "half cooked", but this is true of many bacterial diseases.

- Histopathology is often not helpful.

- Necrosis of cells in proximal convoluted tubules.

- There is also a characteristic degeneration in parts of the brain - focal symmetrical encephalomalacia

- Lesions due to effect of epsilon toxin on blood vessels.