Feline infectious disease

Chlamydia felis (formerly Chlamydophila felis)

Chlamydia felis (formerly Chlamydophila felis and C. psittaci var. felis) predominantly causes conjunctivitis in affected cats but may be involved in upper respiratory tract disease. Infection can become endemic in some cat colonies and recurrent signs are common. An antigen ELISA test and PCR are available for diagnosis. PCR is more sensitive. Conjunctival, nasal or pharyngeal swabs (plain) may be submitted but the organism is reportedly shed predominantly in conjunctival secretions. Samples are collected by reflecting the eyelid and rolling the swab vigorously across the conjunctiva to harvest cells. If necessary, the swab can be moistened with sterile saline prior to sampling. If submission is delayed, then samples may be stored at 2-8°C for up to 48 hours.

Feline leukaemia virus

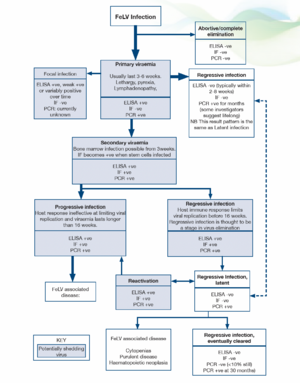

General. The prevalence of FeLV is not clear, but has probably fallen to <1% (Gruffyd Jones 2006). With the introduction of PCR testing our understanding of the pathogenesis and outcomes of infection has been challenged. More recent proposals have suggested the following stages in infection and FeLV status categories (Greene 2012):

Abortive/complete elimination. Virus replicates in local oropharyngeal lymphoid tissue but systemic spread is prevented by humoral and cell-mediated responses. Exposure to infection is indicated by the presence of antibodies but cats are negative for antigen and proviral DNA. It is unclear how often this occurs in natural infection but it is likely to be very uncommon. Studies using newer, sensitive PCR techniques indicate that proviral DNA may be detected at a later date in many patients previously believed to have eliminated the virus. However, the clinical significance of persistence of proviral DNA is unclear since the life expectancy is the same as for cats which have never been infected.

Regressive infection (transient viraemia). Infected cats become viraemic (primary viraemia) but an effective antibody response is mounted and virus replication/viraemia is terminated before or shortly after bone marrow infection (around 3 weeks post infection). In most cats the primary viraemia lasts 3-6 weeks (maximum 16 weeks) during which time, FeLV p27 antigen (ELISA) is detected in the plasma and cats are infectious. Previously, it was thought that termination of the viraemia was accompanied by rapid, total elimination of the virus from all cells (based on negative ELISA results within 2-8 weeks). However, recent studies suggest that FeLV becomes integrated into the cat’s genome and thus can be detected by qPCR for months after the initial viraemia. It has been proposed that integration of proviral DNA is essential for solid protective immunity and some investigators propose that small quantities of proviral DNA may actually persist for life.

The clinical significance of an antigen negative/proviral DNA positive pattern is unclear but cats with this outcome of infection have effective immunity, are likely protected against new exposure and have a low risk of developing FeLV associated diseases. They are unlikely to shed virus via oronasal secretions but may pose a risk to other cats via blood transfusion.

Some cats do not clear the primary viraemia prior to infection of the bone marrow precursors (secondary viraemia) and in these patients viral antigen is detected within platelets and granulocytes by immunofluorescence testing (IF). Once infection is established in the stem cells the virus cannot be eliminated from the bone marrow by the host immune response and most of these patients go on to develop progressive infection (see below). Progressive infection is more likely when viraemia persists for more than 16 weeks. However, in a small number of cats the immune response does limit systemic replication of the virus shortly after bone marrow infection. Although proviral DNA persists in the stem cells of these cats, it is not translated into proteins and affected individuals do not produce virus, become negative for FeLV antigen (ELISA, IF) and are not infectious to other cats. This is termed latency and may be a permanent state but it appears that the majority of cats lose functional viral material for example, through gene reading errors during cell division by 16 months after infection, with only 10% still affected at 30 months.

Regressive (latent) infections may reactivate if the host immunity wanes for example, during pregnancy, periods of stress or after high doses of glucocorticoids. Reactivation is more likely if the stressful event occurs shortly after the initial viraemia and is considered unlikely to occur after 2 years.

Regressive infections are likely to be a stage in the elimination of the virus. Most regressive infections are not clinically significant (reactivation is uncommon under non-experimental conditions) but clinical signs may occur and include cytopaenias, suppurative inflammatory conditions and haematopoietic neoplasia.

Progressive infection

In progressive infections there is an ineffective immune response allowing extensive viral replication in lymphoid tissues, bone marrow and mucosal/glandular tissue, accompanied by virus shedding. If the viraemia persists unchecked for 16 weeks then cats remain persistently viraemic and infectious and most develop FeLV related diseases, often within 3 years. FeLV DNA provirus is detected in both regressive and progressive infections and these can only be differentiated by repeat antigen tests, which in regressive infections become negative after 2-8 weeks, or occasionally, after some months.

Focal Infections

Focal infections of specific tissues (mammary gland, spleen, lymphoid tissue, small intestine) can lead to low grade or intermittent virus production and affected cats may have weak positive or discordant results (ELISA, IF) or variable results over time. They should be considered a potential source of infection to other cats.

Tests for FeLV

ELISA (Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay)

ELISA and rapid immunomigration methodologies are commonly employed in in-clinic tests. They detect free viral protein (p27) in plasma, tears or saliva. Testing serum or plasma is preferred and the use of saliva or tears is not recommended. The specificity of many of these tests is 98-99%, but because of the very low incidence of FeLV, approximately half of the positive tests will be false positives. True positive results could reflect transient or persistent viraemia and further testing (by immunofluorescence) is recommended initially. If immunofluorescence (IF) is initially negative repeat testing 6 and 16 weeks after the initial test is indicated to determine whether the patient has a regressive infection (transient viraemia) or progressive infection. Cats with a persistent ELISA positive, IF negative pattern may have a focal infection.

IF (Immunofluorescence)

IF detects viral protein (p27) in the cytoplasm of leucocytes (predominantly neutrophils) and platelets. Positive results are highly likely to reflect persistent infection, <10% of cats with positive IF result have regressive infections (transient viraemia). IF is a suitable staging test for positive results obtained using ELISA, but is not recommended as an initial screening test because cats with primary viraemia (which may be infectious to other cats) are not detected. False negative IF results may be noted in cats with neutropaenia and/or thrombocytopenia.

FeLV DNA (provirus)

FeLV proviral DNA qPCR allows quantification of FeLV DNA in the blood or bone marrow. High levels are found in ELISA and IF positive cats, low levels are found in cats which are negative using antigen methods. These cats may have latent infections and qPCR is recommended where there is a strong clinical suspicion of FeLV-related disease but negative antigen tests. Cats with regressive and progressive infections are expected to be positive for FeLV proviral DNA thus qPCR will not allow differentiation in ELISA positive patients, particularly in acute infection. In the future, quantification of the viral load in leucocyte subsets may allow differentiation later in the infection, when most cats with virus in the granulocytes have progressive infection while cats with regressive infection appear to possess only a small quantity of proviral DNA in lymphocytes.

As a retrovirus, FeLV mutates naturally and a mutated viral strain may not be detected using specific primers. A negative result does not, therefore, exclude infection.

FeLV infection status

The likely FeLV status of a cat can be determined using the results of ELISA, IF and proviral DNA. However, collection of multiple samples over weeks/months may be required for clarification, particularly for differentiation between regressive infection (transient viraemia) and progressive infection (persistent viraemia). Most cats (>90%) with a positive IF result have progressive infection.

Cats with discordant results (ELISA positive, IF negative) may have a false positive ELISA result, a primary viraemia or focal infection. Isolation of the patient, followed by retesting in 6 weeks and 16 weeks is recommended and provides clarification of the status in many patients. A positive qPCR test would indicate infection and allows confirmation of the infection status (false positive ELISA versus infection). However, a negative qPCR result does not completely exclude infection. Further testing may be required for some individuals.

| Status | ELISA | IF | FeLV DNA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not infected | - | - | - |

| Abortive/complete elimination | - | - | - |

| Regressive (primary viraemia; no secondary viraemia | + | - | + |

| Regressive (with secondary viraemia)* | + | + | + |

| Regressive; latent | - | - | +** |

| Progressive | + | + | + |

| Focal | +/- | - | Currently unknown |

*Most cats with this pattern have progressive disease

**Positive more likely in bone marrow than peripheral blood

When to test for FeLV

Testing is recommended when:

- Cats present with clinical illness (irrespective of previous test results)

- Cats are to be re-homed (even if there are no cats currently in the household). Cats with negative results should be re-tested after at least 4 weeks. Kittens may be tested at anyage but kittens which have been infected by maternal transmission may not be positive for to months after birth (once the virus starts replicating)

- There has been potential exposure to FeLV. If testing is negative then it should be repeated after at least 4 weeks (ideally also after 12 weeks). In a cat with a single exposure the risk of developing progressive infection averages 3% (Greene 2012)

- Cats with high risk lifestyles or living in households with infected cats should be tested on a regular basis. Introduction of an FeLV shedding cat into a group of naive cats for an extended period increases the risk of naive cats developing progressive infection to 30% (Greene 2012)

- Prior to FeLV vaccination. FeLV vaccination does not affect the test result but samples should not be collected shortly after vaccination since some investigators report the risk of detecting vaccine antigens. The duration of this phenomenon is unclear

- Screening of blood donors, using antigen detection methods and qPCR