| This article is still under construction. |

Hydatid Disease (Echinococcus granulosus)

Echinococcus granulosus is an important zoonosis as its metacestode, the hydatid cyst, can develop in humans, as well as in many other animals. The hydatid cyst can grow to the size of a ping-pong ball in sheep, a tennis ball in horses, and a football in man. The metacestode of the related Echinococcus multilocularis (the alveolar cyst) is even more dangerous, but fortunately does not occur in the UK.

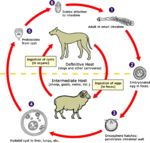

Life-Cycle

The final host of E. granulosus is the dog, fox or other canid. There may be several thousand adult tapeworms in an infected animal. Each adult is less than 0.5cm long with only 3 or 4 segments. The scolex is deeply buried in an intestinal crypt, so microscopic inspection of a mucosal scraping is necessary to detect infection. The prepatent period of E. granulosus is 6-7weeks. No more than one gravid segment is passed by each tapeworm each week. This species therefore has a low biotic potential. The intermediate host is infected by swallowing the eggs. These are half the size of a strongyle egg, and are morphologically indistinguishable from other taeniid eggs.

The metacestode of E. granulosus is the hydatid cyst. These can develop anywhere in the body, but are most frequently found:

- sheep: liver and lungs

- cattle: lungs

- horse: liver

- human: 70% liver, 20% lungs, 10% other sites

Prevalence in the UK:

- human: about 100 new cases of hydatidosis are diagnosed in Britain each year, with 5-10 fatalities occurring. Somw cases are contracted overseas, but endemic “hotspots” occur in Britain, particularly in parts of Wales and some Scottish islands.

- sheep: there is great regional variation. Up to 98% of slaughtered ewes are infected in some localities.

- horses and cattle: up to 10% are infected in some areas.

Epidemiology

E. granulosus has a wide host range and displays great evolutionary plasticity – that is, strains with different biological properties develop readily, each adapted to a particular ecological niche. Extreme examples include dingo-wallaby, wolf-moose and hyena-human cycles. Two strains are recognised in Britain:

1) Dog-sheep strain: infective for cattle and human (not found in Ireland). Dogs become infected if a) fed infected offal, or b) by scavenging dead sheep in hills or on road-side. Sheep dogs are most likely to defaecate in fields around homestead – eggs deposited in faeces and spread across pasture by rain splash, insect activity etc. = sheep become infected when flock brought down for lambing, dipping etc. Humans are infected when eggs from dogs are accidentally ingested (this is normally the only route of infection for humans.

2) Dog-horse strain: more host-specific (in intermediate host) than sheep strain. The horse strain does occur in Ireland, but no human cases reported there – this provides circumstantial evidence that this strain may not be infective for humans. Hunt kennels have been particularly important in dissemination of the horse strain.

Principles of Control

E. granulosus has been eradicated from New Zealand, but this took greater than 20years of intensive effort. Schemes are well advanced in several other countries, but not the UK. To make progress, the following steps must be implemented:

1) Define local epidemiology and collect base-line statistics

2) Registration of all dogs

3) Regular treatment of all dogs (initially at 6week intervals; praziquantel is currently the only suitable drug available – because it is the only drug that kills both adult and immature Echinococcus)

4) Intensive educational programme aimed at farmer and dog owner

5) Regular testing of all dogs to monitor progress and identify non-compliance (the old arecoline purge technique is being replaced by serology or copro-antigen detection)

6) Ensure dogs do not get access to raw offal: meat inspection; burial of carcasses

7) Boiling or freezing offal used for dog food

8) Legislation to enforce compliance

Alveolar Hydatid Disease (E. multilocularis)

This parasite does not occur in the UK. It is largely restricted to forest areas of central Europe (including Switzerland where urban foxes are also infected) and North America. It is a significant public health problem and is spreading across Europe, where 12 countries are now affected compared with four in the 1980’s. The metacestode is the alveolar (or multilocular) cyst. Human infections are particularly dangerous as daughter cysts bud off externally as well as internally from the germinal layer so that the cyst rapidly infiltrates the liver like an invasive tumour, and is inoperable. Dogs, and to a lesser extent cats, can become infected with the adult tapeworm, but the main epidemiological cycle involves the fox as the final host and microtine rodents (particularly voles) as intermediate hosts. The latter have a very short life-span – hence the rapid growth-rate of the alveolar cyst in intermediate hosts, including humans. The anti-rabies campaign in Europe has led to a large increase in the number of foxes and, consequently, of infected rodents.

Echinococcus granulosus in Peritoneal Cavity Parasitic and muscles