Innate Immunity Barriers

Physical Barriers

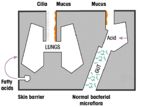

Skin

The simplest way to avoid infection is to prevent microorganisms gaining access to the body. The skin has an external coating of dead cells (cuticle) that, when intact, is impermeable to most infectious agents as very few pathogens are capable of penetrating the thick stratified squamous epithelium of the skin (and lower urinary tract).

- However, infection becomes a problem when there is:

- Skin loss: e.g. burns

- A break in the skin: e.g. wounds

Mucous Membranes

Thin epithelial surfaces are necessary for the normal physiological functions of the body's mucus membranes (ie absorption and gas exchange).They are therefore more susceptible to infection. But it's ok as the body uses alternative protective mechanisms in these areas:

- The mucociliary escalator of the respiratory tract (assisted by coughing and sneezing)

- Peristalsis, vomiting & diarrhoea when necessary removes microorganisms from the Gastro-Intestinal Tract

Biochemical Barriers

Where there are breaks in the skin that are open to the outside environment the body has an armoury of biochemical barrieres that can stop infection. These are:

- Lactic and fatty acids in sweat and sebaceous secretions are directly bacteriocidal

- Enzymes e.g. lysozyme in saliva, sweat & tears and Gastric acid denature microorganisms

- Mucous itself is acidic, indigestible and traps microorganisms

Commensal Organisms

- Out-compete pathogens at mucosal and epithelial surfaces and produce natural antibiotics

- When commensals are disturbed, for example with continual antibiotic use, infection with opportunistic organisms is increased

- E.g. Candida (thrush) or Clostridium difficile (infectious diarrhoea)

| Originally funded by the RVC Jim Bee Award 2007 |