Difference between revisions of "Toxoplasmosis - Sheep"

| (52 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{unfinished}} |

| − | == | + | |

| − | Toxoplasmosis is the disease caused by '' | + | ==Description== |

| + | |||

| + | Toxoplasmosis is the disease caused by ''Toxoplasma gondii'', an intracelluler protozoan parasite. Although the definitive host is the cat, ''T. gondii'' can infect all mammals including man and is a significant cause of abortion in sheep and goats. Toxoplasmosis does not seem to cause disease in cattle. | ||

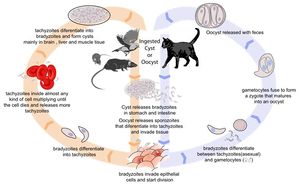

[[Image:Toxoplasmosis Life Cycle.jpg|thumb|right|300px| Life cycle of ''Toxoplasma gondii''. Source: Wikimedia Commons; Author: LadyofHats (2010)]] | [[Image:Toxoplasmosis Life Cycle.jpg|thumb|right|300px| Life cycle of ''Toxoplasma gondii''. Source: Wikimedia Commons; Author: LadyofHats (2010)]] | ||

| − | == | + | ===Life Cycle=== |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | There are three infectious stages of ''Toxoplasma gondii'': 1) sporozoites; 2) actively reproducing tachyzoites; and 3) slowly multiplying bradyzoites. Tachyzoites and bradyzoites are found in tissue cysts, whereas sporozoites are containted within oocysts, which are excreted in the faeces. This means that the protozoa can be transmitted by ingestion of oocyst-contaminated food or water, or by consumption of infected tissue. | |

| + | |||

| + | In naive cats, ''Toxoplasma gondii'' undergoes an enteroepithelial life cycle. Cats ingests intermediate hosts containing tissue cysts, which release bradyzoites in the gastrointestinal tract. The bradyzoites penetrate the small intestinal epithelium and sexual reproductio ensues, eventually resulting the production of oocysts. Oocysts are passed in the cat's faeces and sporulate to become infectious once in the environment. These can then be ingested by other mammals, including sheep. | ||

| + | |||

| + | When sheep ingest oocysts, ''T.gondii'' intiates extraintestinal replication. This process is the same for all hosts, and also occurs when carnivores ingest tissue cysts in other animals. Sporozoites (or bradyzoites, if cysts are consumed) are released in the intestine to infect the intestinal epithelium where they replicate. This produces tachyzoites, which reproduce asexually within the infected cell. When the infected cell ruptures, tachyzoites are released and disseminate via blood and lymph to infect other tissues. Tachyzoites then replicate intracellularly again and the process continues until the host becomes immune or dies. If the infected cell does not burst, tachyzoites eventually encyst as bradyzoites and persist for the life of the host. Cyst are most commonly found in the brain or skeletal muscle, and are a source of infection for carnivorous hosts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Transmission to Sheep=== | ||

| − | + | The ingestion of tissue cysts by cats is of great | |

| − | + | significance, in terms of spread of infection to other | |

| + | animals (Figure 2). Oocysts may be shed continuously | ||

| + | in the faeces from 4 until 14 days after infection, | ||

| + | with an expected peak output of tens of millions at | ||

| + | 6-8 days9. Recrudescence of infection may occur if | ||

| + | the cat is experimentally stressed'0 and perhaps also | ||

| + | through unrelated illness. This can result in the | ||

| + | re-excretion of oocysts in smaller numbers for a | ||

| + | shorter time than in a primary infection. | ||

| + | Cats acquire infection as a result of hunting so that | ||

| + | many will have seroconverted by adulthood. Although | ||

| + | less than 1% may be shedding oocysts at any one | ||

| + | time5, infection may be more prevalent in young cats | ||

| + | taking up hunting for the first time. | ||

| + | Female feral cats can produce two to three litters | ||

| + | a year, each ofup to eight kittens, and may rear their | ||

| + | young communally". Numbers of young cats are | ||

| + | also dependent upon the density of breeding adults. | ||

| + | In rural areas male cats may have territories of 60-80 | ||

| + | hectares (250-200 acres) while females usually only | ||

| + | occupy a 10th of this area"1. In an urban environment | ||

| + | these territories are considerably smaller'2. The area | ||

| + | occupied by feral cats is influenced by the supply | ||

| + | of food, which includes mice, voles, shrews, rats, | ||

| + | rabbits and small birds". | ||

| + | Ingestion | ||

| + | small animals I CATS | ||

| + | INFECTED | ||

| + | WARM-BLOODED | ||

| + | HOSTS | ||

| + | pregnant sheep | ||

| + | ingestion | ||

| + | OOCYSTS contaminate | ||

| + | environment | ||

| + | (e.g. livestock feed and | ||

| + | pasture) | ||

| + | abortion | ||

| + | Figure 2. The spread ofToxoplasma infection to susceptible | ||

| + | pregnant sheep from infected cat faeces deposited in the | ||

| + | environment I | ||

| + | 0141-0768/90/ | ||

| + | 080509-03402.00/0 | ||

| + | 0 1990 | ||

| + | The Royal | ||

| + | Society of | ||

| + | Medicine | ||

| + | 510 Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine Volume 83 August 1990 | ||

| + | The most important sources of feline infection are | ||

| + | chronically-infected birds and rodents6"13, particularly | ||

| + | the latter because they can pass T. gondii infection | ||

| + | from generation to generation without causing | ||

| + | overt clinical disease14'16. In this way a reservoir of | ||

| + | T. gondii tissue cyst infection can exist in a particular | ||

| + | location for a long time, with the potential for | ||

| + | infecting cats and triggering massive oocyst excretion. | ||

| + | The available epidemiological and experimental | ||

| + | evidence suggests that, in the UK, sheep are | ||

| + | frequently maintained in an environment significantly | ||

| + | contaminated with oocysts and that infection follows | ||

| + | ingestion of infected food17"8. Perhaps the most | ||

| + | common source of infection is contaminated pasture. | ||

| + | Certainly, fields treated with manure and bedding | ||

| + | from farm buildings where cats live can cause | ||

| + | infection'9. Careless storage of farm feeds may also | ||

| + | pose a risk20. Fifty grams of infected cat faeces may | ||

| + | contain as many as 10 million oocysts9. If in a | ||

| + | hypothetical situation this was evenly dispersed | ||

| + | throughout 10 tonnes of concentrated animal feed | ||

| + | then each kilogram could contain between five and | ||

| + | 25 sheep-infective doses21. The extent of environmental | ||

| + | contamination with T. gondii oocysts is thus | ||

| + | related to the distribution and behaviour of cats. | ||

| + | Measures to reduce environmental contamination | ||

| + | by oocysts should be aimed at reducing the number | ||

| + | of cats capable of shedding oocysts. This would include | ||

| + | attempts to limit their breeding. If male cats are | ||

| + | caught, neutered and returned to their colonies the | ||

| + | stability ofthe colony is maintained; fertile male cats | ||

| + | do not challenge the neutered males12 and breeding | ||

| + | is controlled. Thus the maintenance ofa small healthy | ||

| + | population of mature cats will reduce oocyst excretion | ||

| + | as well as help to control rodents. Sheep feed should be | ||

| + | kept covered at all times to prevent its contamination | ||

| + | by cat faeces. | ||

==Signalment== | ==Signalment== | ||

| − | |||

==Diagnosis== | ==Diagnosis== | ||

| − | |||

===Clinical Signs=== | ===Clinical Signs=== | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Clinical outbreaks of toxoplasmosis are '''sporadic''' | |

| + | **Immunity is acquired before tupping | ||

| + | **Significant ill-effects are unlikely if immune ewes are infected during pregnancy | ||

| + | **Not shed from sheep to sheep so predicting outbreaks is difficult | ||

===Laboratory Tests=== | ===Laboratory Tests=== | ||

| − | |||

===Pathology=== | ===Pathology=== | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | Aborted ewes show focal necrotic placentitis with white lesions in the cotyledons and foetal tissue | |

==Treatment== | ==Treatment== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Toxovax vaccine | |

| + | ***Live, avirulent strain of ''Toxoplasma'' | ||

| + | ***Does not form bradyzoites or tissue cysts | ||

| + | ***Killed by host immune system | ||

| + | ***Single dose given 6 weeks before tupping | ||

| + | ***Protects for 2 years | ||

| + | ***Immunity boosted by natural challenge | ||

| + | **Medicated feed can be given daily during the main risk period | ||

| + | ***14 weeks before lambing | ||

| + | **The best method of protection is to prevent cats from contaminating the pasture, lambing sheds and feed stores | ||

==Prognosis== | ==Prognosis== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Links== | ==Links== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

#Buxton, D (1990) Ovine toxoplasmosis: a review. ''Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine'', '''83''', 509-511. | #Buxton, D (1990) Ovine toxoplasmosis: a review. ''Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine'', '''83''', 509-511. | ||

#Innes, E A et al (2009) Ovine toxoplasmosis. ''Parastiology'', '''136''', 1887–1894. | #Innes, E A et al (2009) Ovine toxoplasmosis. ''Parastiology'', '''136''', 1887–1894. | ||

#Buxton, D et all (2007) Toxoplasma gondii and ovine toxoplasmosis: New aspects of an old story. ''Veterinary Parasitology'', '''147''', 25-28. | #Buxton, D et all (2007) Toxoplasma gondii and ovine toxoplasmosis: New aspects of an old story. ''Veterinary Parasitology'', '''147''', 25-28. | ||

#Dubey, J P (2009) Toxoplasmosis in sheep — The last 20 years. ''Veterinary Parasitology'', '''163''', 1-14. | #Dubey, J P (2009) Toxoplasmosis in sheep — The last 20 years. ''Veterinary Parasitology'', '''163''', 1-14. | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Tissue_Cyst_Forming_Coccidia]][[Category:Sheep]] | |

| − | + | [[Category:To_Do_-_Lizzie]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Category: | ||

| − | [[Category: | ||

Revision as of 14:45, 13 August 2010

| This article is still under construction. |

Description

Toxoplasmosis is the disease caused by Toxoplasma gondii, an intracelluler protozoan parasite. Although the definitive host is the cat, T. gondii can infect all mammals including man and is a significant cause of abortion in sheep and goats. Toxoplasmosis does not seem to cause disease in cattle.

Life Cycle

There are three infectious stages of Toxoplasma gondii: 1) sporozoites; 2) actively reproducing tachyzoites; and 3) slowly multiplying bradyzoites. Tachyzoites and bradyzoites are found in tissue cysts, whereas sporozoites are containted within oocysts, which are excreted in the faeces. This means that the protozoa can be transmitted by ingestion of oocyst-contaminated food or water, or by consumption of infected tissue.

In naive cats, Toxoplasma gondii undergoes an enteroepithelial life cycle. Cats ingests intermediate hosts containing tissue cysts, which release bradyzoites in the gastrointestinal tract. The bradyzoites penetrate the small intestinal epithelium and sexual reproductio ensues, eventually resulting the production of oocysts. Oocysts are passed in the cat's faeces and sporulate to become infectious once in the environment. These can then be ingested by other mammals, including sheep.

When sheep ingest oocysts, T.gondii intiates extraintestinal replication. This process is the same for all hosts, and also occurs when carnivores ingest tissue cysts in other animals. Sporozoites (or bradyzoites, if cysts are consumed) are released in the intestine to infect the intestinal epithelium where they replicate. This produces tachyzoites, which reproduce asexually within the infected cell. When the infected cell ruptures, tachyzoites are released and disseminate via blood and lymph to infect other tissues. Tachyzoites then replicate intracellularly again and the process continues until the host becomes immune or dies. If the infected cell does not burst, tachyzoites eventually encyst as bradyzoites and persist for the life of the host. Cyst are most commonly found in the brain or skeletal muscle, and are a source of infection for carnivorous hosts.

Transmission to Sheep

The ingestion of tissue cysts by cats is of great significance, in terms of spread of infection to other animals (Figure 2). Oocysts may be shed continuously in the faeces from 4 until 14 days after infection, with an expected peak output of tens of millions at 6-8 days9. Recrudescence of infection may occur if the cat is experimentally stressed'0 and perhaps also through unrelated illness. This can result in the re-excretion of oocysts in smaller numbers for a shorter time than in a primary infection. Cats acquire infection as a result of hunting so that many will have seroconverted by adulthood. Although less than 1% may be shedding oocysts at any one time5, infection may be more prevalent in young cats taking up hunting for the first time. Female feral cats can produce two to three litters a year, each ofup to eight kittens, and may rear their young communally". Numbers of young cats are also dependent upon the density of breeding adults. In rural areas male cats may have territories of 60-80 hectares (250-200 acres) while females usually only occupy a 10th of this area"1. In an urban environment these territories are considerably smaller'2. The area occupied by feral cats is influenced by the supply of food, which includes mice, voles, shrews, rats, rabbits and small birds". Ingestion small animals I CATS INFECTED WARM-BLOODED HOSTS pregnant sheep ingestion OOCYSTS contaminate environment (e.g. livestock feed and pasture) abortion Figure 2. The spread ofToxoplasma infection to susceptible pregnant sheep from infected cat faeces deposited in the environment I 0141-0768/90/ 080509-03402.00/0 0 1990 The Royal Society of Medicine 510 Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine Volume 83 August 1990 The most important sources of feline infection are chronically-infected birds and rodents6"13, particularly the latter because they can pass T. gondii infection from generation to generation without causing overt clinical disease14'16. In this way a reservoir of T. gondii tissue cyst infection can exist in a particular location for a long time, with the potential for infecting cats and triggering massive oocyst excretion. The available epidemiological and experimental evidence suggests that, in the UK, sheep are frequently maintained in an environment significantly contaminated with oocysts and that infection follows ingestion of infected food17"8. Perhaps the most common source of infection is contaminated pasture. Certainly, fields treated with manure and bedding from farm buildings where cats live can cause infection'9. Careless storage of farm feeds may also pose a risk20. Fifty grams of infected cat faeces may contain as many as 10 million oocysts9. If in a hypothetical situation this was evenly dispersed throughout 10 tonnes of concentrated animal feed then each kilogram could contain between five and 25 sheep-infective doses21. The extent of environmental contamination with T. gondii oocysts is thus related to the distribution and behaviour of cats. Measures to reduce environmental contamination by oocysts should be aimed at reducing the number of cats capable of shedding oocysts. This would include attempts to limit their breeding. If male cats are caught, neutered and returned to their colonies the stability ofthe colony is maintained; fertile male cats do not challenge the neutered males12 and breeding is controlled. Thus the maintenance ofa small healthy population of mature cats will reduce oocyst excretion as well as help to control rodents. Sheep feed should be kept covered at all times to prevent its contamination by cat faeces.

Signalment

Diagnosis

Clinical Signs

- Clinical outbreaks of toxoplasmosis are sporadic

- Immunity is acquired before tupping

- Significant ill-effects are unlikely if immune ewes are infected during pregnancy

- Not shed from sheep to sheep so predicting outbreaks is difficult

Laboratory Tests

Pathology

Aborted ewes show focal necrotic placentitis with white lesions in the cotyledons and foetal tissue

Treatment

- Toxovax vaccine

- Live, avirulent strain of Toxoplasma

- Does not form bradyzoites or tissue cysts

- Killed by host immune system

- Single dose given 6 weeks before tupping

- Protects for 2 years

- Immunity boosted by natural challenge

- Medicated feed can be given daily during the main risk period

- 14 weeks before lambing

- The best method of protection is to prevent cats from contaminating the pasture, lambing sheds and feed stores

Prognosis

Links

References

- Buxton, D (1990) Ovine toxoplasmosis: a review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 83, 509-511.

- Innes, E A et al (2009) Ovine toxoplasmosis. Parastiology, 136, 1887–1894.

- Buxton, D et all (2007) Toxoplasma gondii and ovine toxoplasmosis: New aspects of an old story. Veterinary Parasitology, 147, 25-28.

- Dubey, J P (2009) Toxoplasmosis in sheep — The last 20 years. Veterinary Parasitology, 163, 1-14.