Difference between revisions of "Behavioural Consultation and History Taking"

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

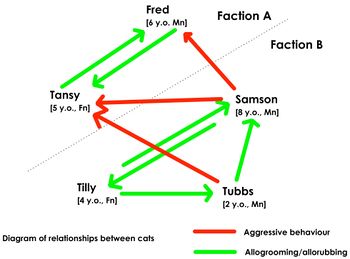

[[File:Cat relationships example.jpg|350px|thumb|right|Fig. 1: Example of a diagram illustrating the relationships between cats within the same household]] | [[File:Cat relationships example.jpg|350px|thumb|right|Fig. 1: Example of a diagram illustrating the relationships between cats within the same household]] | ||

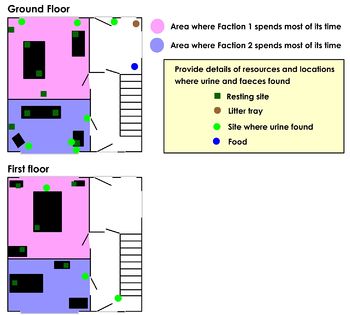

[[File:Houseplan 2.jpg|thumb|right|350px|Fig.2: Example of a house plan diagram]] | [[File:Houseplan 2.jpg|thumb|right|350px|Fig.2: Example of a house plan diagram]] | ||

| − | The majority of behavioural cases presented in veterinary practice are related to [[Normal Feline Behaviour|normal feline behaviour]]. However, it is | + | The majority of behavioural cases presented in veterinary practice are related to [[Normal Feline Behaviour|normal feline behaviour]] that is expressed in an inappropriate or undesirable context. However, it is important to be aware that health problems are a common causal or underlying factor in behavioural problems in cats. For example, lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) and [[Housesoiling - Cat|housesoiling]] and indoor urine marking are commonly linked. A full physical and clinical examination should be completed before any type of behavioural therapy is implemented. Behavioural changes may precede clinical signs, and also persist after an illness is apparently resolved. |

| − | + | *Conditions that alter motivation: Polyphagia and polydipsia ([[Diabetes Mellitus|e.g. due to diabetes mellitus]] or [[Hyperthyroidism]]) can lead to competition over resources, pain can cause increased defensive behaviour, and sickness behaviour (due to the effect of inflammatory cystokines) can cause reductions in activity and social tolerance. | |

| − | *[[Diabetes Mellitus|Diabetes mellitus]]: cats initially presented for | + | *Conditions that alter perception or cognition: Decreased awareness of signalling can lead to interact conflict (e.g. visual impairment), and cognitive dysfunction can lead to confusion, anxiety and irritability. |

| − | *[[Hyperthyroidism]]: [[Feline Aggression|aggression]] to both or either other cats or owners | + | |

| + | *Conditions altering water balance ([[Diabetes Mellitus|Diabetes mellitus]], renal insufficiency): cats initially presented for indoor elimination | ||

| + | *Conditions [[Hyperthyroidism]]: [[Feline Aggression|aggression]] to both or either other cats or owners | ||

As well as behavioural expressions of physical disease, behavioural symptoms can result as a outcome of shifts in neurochemical equilibriums in the CNS. | As well as behavioural expressions of physical disease, behavioural symptoms can result as a outcome of shifts in neurochemical equilibriums in the CNS. | ||

Revision as of 12:30, 9 September 2014

Introduction

The majority of behavioural cases presented in veterinary practice are related to normal feline behaviour that is expressed in an inappropriate or undesirable context. However, it is important to be aware that health problems are a common causal or underlying factor in behavioural problems in cats. For example, lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) and housesoiling and indoor urine marking are commonly linked. A full physical and clinical examination should be completed before any type of behavioural therapy is implemented. Behavioural changes may precede clinical signs, and also persist after an illness is apparently resolved.

- Conditions that alter motivation: Polyphagia and polydipsia (e.g. due to diabetes mellitus or Hyperthyroidism) can lead to competition over resources, pain can cause increased defensive behaviour, and sickness behaviour (due to the effect of inflammatory cystokines) can cause reductions in activity and social tolerance.

- Conditions that alter perception or cognition: Decreased awareness of signalling can lead to interact conflict (e.g. visual impairment), and cognitive dysfunction can lead to confusion, anxiety and irritability.

- Conditions altering water balance (Diabetes mellitus, renal insufficiency): cats initially presented for indoor elimination

- Conditions Hyperthyroidism: aggression to both or either other cats or owners

As well as behavioural expressions of physical disease, behavioural symptoms can result as a outcome of shifts in neurochemical equilibriums in the CNS. Additionally, high levels of stress can cause alterations in behavioural, physiologic and immune responses. Alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary axis have been linked to stress as well as effects on levels of dopamine, serotonin, noradrenaline and prolactin. In animals, stress is a contributing factor to gastrointestinal disturbances, skin conditions, feline interstitial cystitis as well as compulsive disorders and increased fear responses.

History Taking

As with other areas of veterinary practice, a thorough history is paramount. In a behavioural context history taking must be especially thorough and can be a very long process. Initially, it must be determined what the issue is from the client’s perspective and what they are expecting as a solution. It is important to collect information about the cat’s environment and not centre solely on the presenting behaviour. The history should also cover the medical background of the cat, the upbringing of the animal, current lifestyle and information about the specific problem which is of concern.

Key points in a behavioural history should cover:

- Clinical history

- Any current drugs being administered

- Any former behavioural therapy as well as corrective measures being implemented and their effectiveness.

- The animal’s disposition

- Breeding and early upbringing

- Current lifestyle - environment and housing

- Relationship between pet and owner

- The rate of occurrence of problem behaviour and its predictability

- A thorough description of the issue, along with information about time and age of onset, duration of episodes, frequency and development including any alterations in pattern.

- The owners response to the issue

Considering what happens before and after the problem behaviour is also important as this can often provide a clue to the stimulus. In addition videos or visits to the animals normal environment may be useful.

Social Structure within the Home

If more than one cat resides within the same home, it is important to establish their relationship. An interactive diagram is ideal, similar to the one in the figure 1. image. Record the friendly and aggressive behaviours between individuals:

- Friendly: e.g. grooming, rubbing against, tail-up greeting

- Aggressive: e.g. chasing, growling, hissing, spitting, fighting

It is possible to have no affiliative behaviour at all between a whole group of cats, or a to find that there is a single outsider. Factions often require their own resources so that they can coexist without competition.

House Layout

Draw a diagram of the house to show where the cats have food, water, litter trays and cat flap (similar to the figure 2. image). Also mark on this where urine or faeces have been found and which cat left them, if relevant. This is particularly important in cases of housesoiling but is useful in other cases too as it helps to establish the appropriate allocation of resources.

Feeding

Find out which type of food is the cat fed (dried, moist etc) and how many times a day or whether food is available for thee cats at all times. Do the cats often leave food after each meal?

Outdoor Access

Information about access to the outdoors also plays a vital part of a feline behavioural consultation. The main question is whether the cat has any outdoor access at all, then to what extent and whether it can control its own access. The questions asked should be similar to: Can the cats go outdoors? Does the owner have to let them in and out? Is there a cat flap? If so, is it open at all times? Is it an electronic/magnetic coded one? Do the cats have other ways in and out of the house [windows etc]? Are any of the cats reluctant to go out? Is there a reason the owner is aware of why they won’t go out? Do any of the cats go to the toilet in the garden?

More detailed information is then obtained depending on the main problem:

References

- Heath, S. Chapter 5, Common Feline Behavioural Problems – Feline Medicine and Therapeutics. 2004 British Small Animal Veterinary Association.

- Merck Veterinary Manual (10th Edition) - Behaviour. 2011 The Merck Publishing Group.

| This article is still under construction. |