Also Known As: Gall sickness — Gallsickness — Tick fever (Australia) — Tristeza (Portugal)

Caused by: Anaplasma marginale — A. ovis — A. mesaeterum — Ehrlichia bovis

Introduction

Anaplasmosis is a ruminant disease caused by the rickettsial pathogens Anaplasma marginale, A. ovis, A. mesaeterum and Ehrlichia bovis. These rickettsial parasites reside exclusively within the red blood cells of their hosts.

Cattle, sheep, deer, antelope and wild ruminants can all be affected. A. marginale is usually the causative agent in cattle and wild ruminants, while A. ovis is most commonly isolated in sheep and goats.

A. centrale caused mild disease in cattle and is now the foundation for some vaccines. A. mesaeterum is similar to A. ovis but has a lower pathogenicity.

This disease is notifiable to the World Organisation of Animal Health (OIE)

Signalment

The resistance of Bos indicus cattle to ticks may reduce the rate of transmission in this breed.

No other breed predilection is evident.

Maternal derived immunity in calves is followed by age related immunity, and thus animals do not appear susceptible to anaplasmosis until 9-12 months old. Exposure before this age often results in lifelong, protective immunity providing endemic stability even in the presence of disease and vectors.

No marked age vulnerability appears to exist in sheep and all ages appear to acquire disease equally although it is usually mild but is exacerbated by stress.

Distribution

Anaplasmosis occurs most commonly in tropical and subtropical regions, particularly South and Central America, USA, Africa, Australia and Southern Europe. This climate supports the insect and mechanical vectors required for transmission of the parasite.

Its use of other insect vectors such as the Culicoides midge and biting flies mean that distribution of Anaplasmosis is inceasing all the time.

Transmission

Anaplasmosis is not directly contagious and most transmission occurs via ticks.

Cattle that recover become persistent carriers and although clinical signs do not recrudesce, sequential ricketssial lifecycles are ongoing and therefore reinfection of insect vectors and transmission to other vulnerable animals continues.

Transplacental transmission from infected dams can also occur.

Anaplasmosis is not considered zoonotic.

Clinical Signs

Cardiovascular

- Profound anaemia resulting in tachycardia and dyspnoea. Congestion of mucous membranes which may be jaundiced.

Gastrointestinal

- Anorexia and mucoid diarrhoea, rumenal atony, excess salivation.

Urinary

- Haemoglobinuria does not occur

Neurological signs

- Shivering, fasciculations, ataxia, seizures, syncope

Reproductive

- Abortion, infertility, agalactia

Other

- General paresis/paralysis, rough hair coat, weight loss

Signs are often severely exacerbated by exercise with caution needed not to overly stress animals during clinical examination which can lead to collapse and death.

Diagnosis

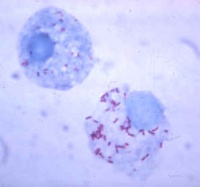

Identification of the organism within the erythrocytes on a thin blood smear with Giemsa staining is both uncomplicated and definitive. A positive result is deemed as >5% red blood cells infected or accompanying anaemic signs. The number of infected cells doubles every 24 - 48h and may reach 90%.

The degree of parasitaemia is much lower in sheep and goats.

Complement fixation is the current international test but it lacks sensitivity.

On post mortem, carcasses are emaciated and blood is thin and watery. Jaundice is often evident and the spleen may be engorged as a consequence of profound anaemia. Serous effusions may be present in any body cavity. The spleen may be engorged and the kidneys congested.

Urine is dark yellow/brown due to the presence of bilirubin. The absence of haemoglobinuria/haematuria is a useful sign to distinguish the condition from other differential diagnoses that present in a similar way.

Treatment

Oxytetracycline and Imidocarb are both highly effective and prompt treatment usually ensures survival for all but the most severely affected individuals. Note that imidocarb is not approved for use in some countries.

Supportive treatment such as blood transfusions and appetite stimulants in severe cases may be required.

A long combined course of imidocarb and oxytetracycline can also be used to try and eliminate the carrier state. However, a trial into using oxytetracycline for this purpose showed it to be ineffective for this purpose (Coetzee et al, 2005).

Control

Vaccines against anaplasmosis are available, all are derived from the blood of infected cattle. Both live and killed forms are available.

Detection and culling or treatment of carrier animals is essential.

Take care when performing veterinary and husbandry procedures to prevent iatrogenic transmission with contaminated instruments.

Control of the tick vector is viable but expensive.

| Anaplasmosis Learning Resources | |

|---|---|

Test your knowledge using flashcard type questions |

Anaplasmosis Flashcards |

Search for recent publications via CAB Abstract (CABI log in required) |

Anaplasmosis Publications |

References

Coetzee et al (2005) Comparison of three oxytetracycline regimes for the treatment of persistent Anaplasma marginale infections in beef cattle. Veterinary Parasitology 127:61-73.

|

This article was originally sourced from The Animal Health & Production Compendium (AHPC) published online by CABI during the OVAL Project. The datasheet was accessed on June 2, 2011. |

| This article has been peer reviewed but is awaiting expert review. If you would like to help with this, please see more information about expert reviewing. |