Fasciola hepatica

| Also known as: | Liver Fluke |

Fasciola Hepatica is an hepatic parasite found in mainly in ruminants, namely cows, sheep and goats, but also known to affect horses and pigs. It is found Worldwide, and within the UK, with its prevalence ever increasing. It is responsible for a 10-15% production loss in each infected animal, as it affects meat, milk and wool production, so is of huge economic consequence.

Fasiola Hepatica has a definitive ruminant mammalian host and an intermediate molluscian host. Within Europe the intermediate host is almost exclusively the snail 'Lymnaea truncatulata'. The snail habitat is crucial to the survival of the parasite, so wet conditions are favourable to the development and spread of Fasciola hepatica

| Kingdom | Animalia |

| Phylum | Platyhelminthes |

| Class | Trematoda |

| Subclass | Digenea |

| Order | Echinostomida |

| Family | Fasciolidae |

| Genus | Fasciola |

| Species | F. Hepatica |

Pathogenesis

The severity of the infection is mainly dependent on the number of metacercariae ingested. The Pathogenesis is often described as two-fold. The first stage occuring when the parasite migrates through the liver parenchyma, causing liver damage and haemorrhage. The second phase occurs when the parasite is in the bile ducts, and damage is a result of the haematophagic activity of the adult flukes.

Acute Fascioliasis

The acute disease is a less common type of Fasciola hepatica, and generally occurs 2-6 weeks after large ingestion of metacercariae. The young liver flukes migrate through the liver parenchyma causing severe haemorrhaging, due to the damage to the liver vasculature.

This occurs in late autumn and winter, mainly between the months of August to October. Outbreaks of acute fascioliasis usually present as sudden deaths. On examination infected animals are weak, with pale mucous membranes. They may also have enlarged livers, and the liver surface may be cover with a fibrinous peritonitis, particularly evident on the ventral lobe. Tracts become filled with blood and degenerate hepatocytes later infiltrated with eosinophils, lymphocytes and replaced by fibrosis.

Subactute Fascioliasis

This is caused by ingestion of metacercariae over a longer period of time. Some may have migrated to the bile ducts, causing cholangitis, whilst other metacercariae are migrating through the liver causing lesions similar to those present in acute fascioliasis. The infected host may present with severe haemorrhagic anaemia, with hypoalbuminaemia, rapid loss of body condition, reduced appetite, pale mucous membranes, and submandibular oedema may also be present. On post-mortem, an enlarged liver is common and haemorrhagic tracts are usually visible on the liver surface. If left untreated, it is often fatal. This form of fascioliasis occurs around 6-10 weeks after ingestion of the metacercariae by the host, and like acute fascioliasis occurs in late autumn and winter.

Chronic Fascioliasis

This is usually seen in late winter, early spring and is currently the most common fascoloiasis seen. It occurs around 4-5 months after ingestion of the metacercariae. Hypochromic and macrocytic anaemia and hypoalbuminaemia are common, as the adult flukes are capable of sucking up to 0.5ml of blood each day. In heavy infections, this can prove to be a severe loss.

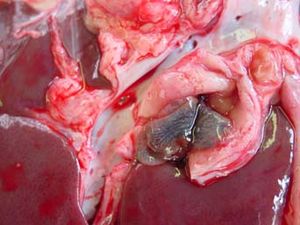

Infected animals may present with progressive loss of body condtion, reduced appeptite, which along with hypoalbuminaemia can result in an gaunt animal. Other common signs include pale mucous membranes, and submandibular oedema, more commonly known as 'bottle jaw.' On biopsy the liver will have an irregular shape, distorted shape with areas of fibrous tissue replacing the cells damaged by the migrating flukes. The bile ducts appear dilated, and dark, and it is often possible to express numerous numbers of adult flukes from within the ducts. Pathology is similar in both sheep and cattle, expect in cattle you may see calcification of the bile ducts, and enlargement of the gall bladder. The calcified bile ducts are often seen protruding from the liver surface, which is known as 'pipe stem liver.'

Diagnosis

This is performed primarily on the clinical findings, seasonal occurance, as well as a previous history of fasciolosis on the farm. These along with post-mortem form the basis for diagnosis of Fasciola hepatica. In practice, diagnosis of ovine fasciolosis is often more straightforward than bovine fasciolosis.

Examination of faeces for liver fluke eggs is also useful, and may be complemented by laboratory tests. Firstly the measurement of Glutamate dehydrogenase (GLDH) is used. This is an enzyme released by damaged hepatic cells, and levels become elevated within the first few weeks of infection. Another test commonly used is measuring the glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), and this indicates damage to the epithelial cells of the bile ducts, and is seen later in the cycle, and maintained for a longer duration.

An ELISA can also be used in the detection process. It identifies antibodies against flukes in the serum and milk samples, and is deemd to be extremely reliable in this case.

Treatment

If the fuke is present treat with triclabendazole, which is effective against all stages of Fasciola hepatica. Treatment should be applied in September/October and again in January, if faecal egg count is still postitive. One may also treat against adult only stages in May/June, preventing any future pasture contamination. However, do not use the same treatment in September/October as used in May/June, as resistance to drugs is becoming a real problem within the UK due to overuse. If it has been a particularly wet season, it may be necessary to treat again, as Fasciola hepatica becomes more prevalent under such conditions.

Isolation and treatment of all new animals entering from another farm has also be shown to be effective. Other control measures include fencing off wet areas, and increasing soil drainage.

References

Taylor, M.A, Coop, R.L., Wall,R.L. (2007) Veterinary Parasitology Blackwell Publishing

G.L. Pritchard et al., Emergence of fasciolosis in cattle in East Anglia, The Veterinary Record, Novemeber 5, 2005.