Equine Protozoal Myeloencephalitis

| This article is still under construction. |

| Also known as: | EPM Equine protozoal myelitis |

Description

A progressive, infectious,[1]neurological disease of horses, endemic in the USA[2] and only encountered elsewhere in imported equids.[3] EPM is one of the most frequently diagnosed neurological conditions of the Western Hemisphere[4] and the principal differential for multifocal, asymmetric progressive central nervous system (CNS) disease.[1] As it can resemble any neurological disorder, EPM must be considered in any horse with neurological signs if it resides in the Americas or if it has been imported from that area[2][5] The disease is not contagious.[1]

Aetiology

EPM results from infection of the CNS by the apicomplexan parasite Sarcocystis neurona or, less frequently, its close relative Neospora hughesi.[6][7] These protozoans develop within neurons[4] causing immediate or inflammatory-mediated neuronal damage. The organisms migrate randomly through the brain and spinal cord causing asymmetrical lesions of grey and white matter and thus multifocal lower and upper motor neuron deficits.[1]

Epidemiology

In endemic areas of the United States, around a quarter of referrals for equine neurological disease are attributed to EPM.(22,23 in Furr) According to the United States Department of Agriculture, the average incidence of the disease is 14 cases per 10,000 horses per year. However, the challenges of obtaining a definitive diagnosis may mean this figure is an underestimate (Furr). The disease has been identified in parts of Central and South America, southern Canada and across most of the USA.(Furr) EPM is noted occasionally in other countries, in horses that have been imported from the Americas.(28,29 in Furr). It is likely that these animals underwent transportation carrying a silent but persistent infection. There have been reports of EPM in horses that have not travelled to or from endemic regions(Furr), although cross-reacting Ags on the immunoblot test may explain this discrepancy(Furr).

The route of infection remains unconfirmed, (Pasq) but there is an increased risk associated with a young age (1-4yrs) (IVIS 3) and autumn months (24 in Furr). The reported age range for EPM cases is currently 2 months (34 in furr) to 24 years (35 in Furr). Thoroughbreds, Standardbreds and Quarterhorses are most commonly affected across the US and Canada (30 in Furr). This may relate to a breed predispostion or alternatively, managemental factors associated with these breeds(32 in Furr). Showing, racing (25 in Furr) and stress(25 in Furr) have been linked to a greater risk of clinical disease(IVIS 2). Case clustering may occur where all the risk factors are in operation, most cases appear in isolation (Furr).

Additonal risk factors for EPM: opossums seen on farm, woods on famr, (Furr), increased numbers of hroses, purchase dvs home-forwn grain, use of wood chips or shavings as bedding, presence of rats or mice, increased pop density

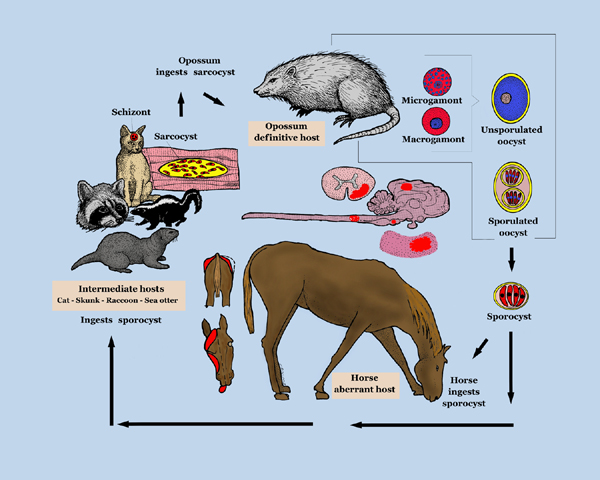

Life Cycle

Signalment

Mostly Standardbreds and Thoroughbreds aged 1-6years.[1] Foal infection may be possible.[2]

Clinical Signs

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnoses

The protozoan can migrate to any region of the CNS[2], thus the differential list comprises almost all diseases of this system.[4]

| Differential | Differentiating signs | Tests to rule out |

| Cervical vertebral malformation (CVM, cervical compressive myelopathy, cervical vertebral instability, cervical stenotic myelopathy, cervical spondylomyelopathy, Wobbler's syndrome). | Symmetrical gait deficits, worse in pelvic limbs[8] with spasticity and dysmetria, good retention of strength, no muscle wasting.[4] NB:can be concurrent with EPM.[9] | Plain lateral radiography of C1 to T1[9], myelography. [10] |

| West Nile encephalitis | Systemically ill, pyrexia. Difficult to differentiate if horse is afebrile and has no excessive muscle fasciculations.[11] | Leukogram, CSF analysis, IgM capture ELISA, plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT).[10] |

| WEE | Systemically ill, pyrexia, abnormal motor function.[11] | Leukogram, ELISA, titres, virus isolation.[10] |

| EEE | Systemically ill, pyrexia, abnormal motor function[11], rapidly progressive.[10] | Leukogram, CSF analysis, ELISA, titres, virus isolation.[10] |

| VEE | Systemically ill, pyrexia. | Leukogram, IgM ELISA[12] |

| Equine herpesvirus-1 myeloencephalopathy | Sudden onset and early stabilization of neurological signs, multiple horses affected, recent fever, abortion.[13] Dysuria not often seen in EPM.[4] | CSF analysis, PCR[4], titres, virus isolation.[10] |

| Rabies | Rapid progression[14], behavioural alterations, depression, seizure, coma.[11] | Post-mortem fluorescent antibody testing of brain required for definitive diagnosis.[14] |

| Polyneuritis equi (previously cauda equina neuritis) | Cranial nerve deficits are peripheral with no change in attitude.[15] | Western blot analysis of CSF.[16] |

| Equine degenerative myeloencephalopathy | Symmetrical signs.[17] | May get increased CSF creatinine kinase (CK)[18] and reduced serum Vitamin E concentrations but these are unreliable for ante mortem diagnosis.[17] |

| Verminous encephalomyelitis | Acute onset. | CSF analysis.[19] |

| Bacterial meningoencephalitis | Stiff neck.[1] | |

| CNS abscessation due to 'bastard strangles'[4] | History of Streptococcus equi subsp. equi infection.[20] | CSF analysis (severe, suppurative inflammation), culture of CSF.[20] |

| Spinal trauma[1] | History (usually acute onset neurological signs), usually solitary lesion localised by neurological exam.[21] | Radiography, myelography, CT, MRI, nuclear scintigraphy, ultrasound, CSF analysis, nerve conduction velocities, EMG, transcranial magnetic stimulation.[22] |

| Occipito-atlanto-axial malformation (OAAM) | Deficits develop before 6mths in Arabian horse.[23] | Radiography.[10] |

| Spinal tumor | Signs can usually be localized to one region of the CNS. | CT, MRI. Definitive diagnosis requires cytology, biopsy, histopathology or CSF analysis.[24] |

| Sorghum cystitis/ataxia[1] | Posterior ataxia or paresis, cystitis, history of grazing Sorghum species[25] | Demonstration of cystitis or pyelonephritis by laboratory methods, but not specific.[26] |

Pathology

Widespread lesions of the CNS are typically observed in horses.[4]

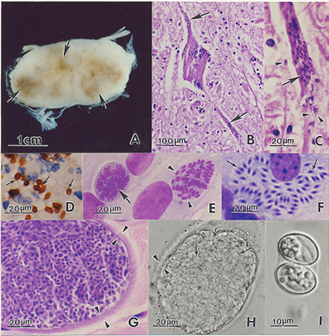

Gross exam

Lesions may be up to several centimetres across.[4] They range from mild discolouration to multifocal areas of haemorrhage and/or malacia[27] of the brain, spinal cord and less commonly, peripheral nerves.[4]

Histopathology

Microscopically, both grey and white matter may be affected with focal to diffuse areas of nonsuppurative inflammation, necrosis and neuronal destruction. Perivascular infiltrates comprise lymphocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, giant cells, eosinophils and gitter cells.[4] In around 25% of cases, schizonts or merozoites may be found in the neuronal cytoplasm.[27] Less frequently, protozoa parasitize intravascular and tissue neutrophils and eosinophils, capillary endothelial cells and myelinated axons[4][27]. Free merozoites may be seen in necrotic regions. If organisms are absent, the diagnosis relies on recognition of the inflammatory changes described above.[27]

Treatment

Prognosis

Depends on duration and severity of neurological signs[3] but clinical resolution is more likely if the condition is diagnosed and treated early.[2] With standard therapy, involving 6-8months of ponazuzril or pyrimethamine-sulfadiazine (V), there is a recovery rate of around 25% and an improvement in 60-75% of cases.[28] A good prognosis might be expected if there is an improvement in clinical signs within two weeks of commencing anti-protozoal and anti-inflammatory treatment (V). The prognosis will be guarded to poor[1] for a horse with severe irreversible neuronal damage or one that has not been diagnosed or treated appropriately (V).

Prevention

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Pasquini, C, Pasquini, S, Woods, P (2005) Guide to Equine Clinics Volume 1: Equine Medicine (Third edition), SUDZ Publishing, 245-250. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Pasq" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "Pasq" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "Pasq" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "Pasq" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "Pasq" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "Pasq" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "Pasq" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Gray, L.C, Magdesian, K.G, Sturges, B.K, Madigan, J.E (2001) Suspected protozoal myeloencephalitis in a two-month-old colt. Vet Rec, 149:269-273. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "EPM8" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 3.0 3.1 Vatistas, N, Mayhew, J (1995) Differential diagnosis of polyneuritis equi. In Practice, Jan, 26-29.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 Furr, M (2010) Equine protozoal myeloencephalitis in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.

- ↑ DEFRA, The Animal Health Trust, The British Equine Veterinary Association (2009) Surveillance: Equine disease surveillance, April to June 2009, The Vet Rec, Oct 24:489-492.

- ↑ Dubey, J.P, Lindsay, D.S, Saville, W.J, Reed, S.M, Granstrom, D.E, Speer, C.A (2001)A review of Sarcocystis neurona and equine protozoal myeloencephalitis (EPM). Vet Parasitol, 95:89-131. In: Pusterla, N, Wilson, W.D, Conrad, P.A, Barr, B.C, Ferraro, G.L, Daft, B.M, Leutenegger, C.M (2006) Cytokine gene signatures in neural tissue of horses with equine protozoal myeloencephalitis or equine herpes type 1 myeloencephalopathy. Vet Rec, Sep 9:Papers & Articles.

- ↑ Wobeser, B.K, Godson, D.L, Rejmanek, D, Dowling, P (2009) Equine protozoal myeloencephalitis caused by Neospora hughesi in an adult horse in Saskatchewan. Can Vet J, 50(8):851-3.

- ↑ Mayhew, I.G, deLahunta, A, Whitlock, R.H, Krook, L, Tasker, J.B (1978) Spinal cord disease in the horse, Cornell Vet, 68(Suppl 8):110-120. In: Hahn, C.N (2010) Cervical Vertebral Malformation in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Hahn, C.N (2010) Cervical Vertebral Malformation in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Seino, K.K (2010) Spinal Ataxia in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 3.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Long, M.T (2010) Flavivirus Encephalitis in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.

- ↑ Bertone, J.J (2010) Viral Encephalitis in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.

- ↑ Wilson, W.D, Pusterla, N (2010) Equine Herpesvirus-1 Myeloencephalopathy in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Sommardahl, C.S (2010) Rabies in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.

- ↑ Scaratt, W.K, Jortner, B.S (1985) Neuritis of the cauda equina in a yearling filly. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet, 7:S197-S202. In: Saville, W.J (2010) Polyneuritis equi in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.

- ↑ Granstrom, D.E, Dubey, J.P, Giles, R.C (1994) Equine protozoal myeloencephalitis: biology and epidemiology. In Nakajima, H, Plowright, W, editors: Refereed Proceedings, Newmarket, England, R & W Publications. In: Saville, W.J (2010) Polyneuritis equi in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Nout, Y.S (2010) Equine Degenerative Myeloencephalopathy in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.

- ↑ Mayhew, I.G, deLahunta, A, Whitlock, R.H, Krook, L, Tasker, J.B (1978) Spinal cord disease in the horse, Cornell Vet, 68(Suppl 8):1-207. In: Nout, Y.S (2010) Equine Degenerative Myeloencephalopathy in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.

- ↑ Jose-Cunilleras, E (2010) Verminous Encephalomyelitis in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Byrne, B. A (2010) Diseases of the Cerebellum in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.

- ↑ Smith, P.M, Jeffery, N.D (2005) Spinal shock - comparative aspects and clinical relevance. J Vet Intern Med, 19:788-793. In: Nout, Y.S (2010) Central Nervous System Trauma in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.

- ↑ Nout, Y.S (2010) Central Nervous System Trauma in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.

- ↑ Watson, A.G, Mayhew, I.G (1986) Familial congenital occipitoatlantoaxial malformation (OAAM) in the Arabian horse. Spine, 11:334-339. In: Seino, K.K (2010) Spinal Ataxia in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 3.

- ↑ Sellon, D.C (2010) Miscellaneous Neurologic Disorders in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.

- ↑ Talcott, P (2010) Toxicoses causing signs relating to the urinary system in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 22.

- ↑ Talcott, P (2010) Toxicoses causing signs relating to the urinary system in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 22.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Merck & Co (2008) The Merck Veterinary Manual (Eighth Edition), Merial

- ↑ MacKay, R.J (2006) Equine protozoa myeloencephalitis: treatment, prognosis and prevention. Clin Tech Equine Pract, 5:9-16. In: Furr, M (2010) Equine protozoal myeloencephalitis in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.