| This article has been peer reviewed but is awaiting expert review. If you would like to help with this, please see more information about expert reviewing. |

Description

NOTIFIABLE and ZOONOTIC OIE List B, infectious, mosquito-borne diseases of equidae affecting the central nervous system (CNS). They include:

- Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE)

- Western Equine Encephalitis (WEE)

- Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis (VEE) - reportable in the USA[1]

Aetiology

See this page for details of the causal pathogens. Some of the virus strains can infect swine[2], poultry and other farmed birds including quail and ratites.[3] Isolated cases have also been noted in cattle[4], sheep and non-domestic ungulates.[3] Some strains are potential agents of biowarfare or bioterrorism[5].

Epidemiology

Distribution

Togaviral encephalitis in equids is largely confined to the Western Hemisphere.[3] Venezuelan EEV can cause large outbreaks of disease over extensive geographical areas in both humans and horses. Spread of this virus into Central America has had disasterous consequences with epidemics as far north as Texas.[6] Climatic conditions and interventions that support vector populations, such as irrigation, greatly influence the geographical spread of the disease.[6] EEE has been recorded across the United States, but mostly in the Southeastern States.[3] As its names suggests, WEE has a predilection for the Western states which have been subject to significant outbreaks in the past. A regional alteration in virulence has been proposed for the steep decline in clinical case numbers observed in this area.[3] A lag phase of 2-5weeks is commonly observed between horse and human cases of WEE in a given locus.[7] Both are dead-end hosts for the virus. A subtype of Western EEV, Highlands J virus, was isolated from the brain of a horse with encephalitis in Florida.[8]

Transmission

Transfer is vector-mediated, primarily via mosquito salivary transfer. WEE and VEE may also be transmitted horse to horse through nasal secretions. This mode of transmission is less likely, despite the fact that high concentrations of VEE virus are found in ocular and nasal discharges from infected horses.[9] The viraemic phase ends when nervous signs develop[3] and is important for disease amplification. Amplification from horses is likely only with VEE virus, in association with a relatively high and potentially persistent viraemia.[10] Similarly, zoonotic spread is unlikely for Eastern and Western equine encephalitis, but has been noted with VEE.

Seasonal Incidence

The disease is not directly contagious between horses and humans but occurs sporadically in both species from mid-summer to late autumn - during the height of the vector season.[1] Case numbers peak in June to November in temperate climates.[3] The vector season is longer in warmer climates, where the disease period is prolonged. Global warming may promote more outbreaks in historically colder climates.[3]

Epidemics

Outbeak prediction to date has been inaccurate, implying that other, unidentified factors may be in operation.[3] However, some epidemic requirements are beyond question. Adequate amounts of infective virus, sufficent vectors, infected sylvatic hosts and susceptible terminal hosts, and finally, appropriate reservoirs, are all crucial.[11]

Pathogenesis[3]

Upon entry to the host, viruses multiply in the muscle, enter the lymphatic circulation and localize in lymph nodes. In macrophages and neutrophils viral replication leads to shedding and significant clearance of viral particles. No further clinical signs develop if this clearance is successful. Erythrocyte and leukocyte absorption are used to circumvent the immune defences of the host. After incomplete elimination, residual virus infects endothelial cells and accumulates in highly vascular organs such as the liver and spleen. In these organs, viral replication produces circulating virus and a second viraemic period, typically associated with early clinical signs. Neuroinvasion and replication occurs within a week.[10] An incubation period of 7-21days has been demonstrated after experimental infection with Eastern or Western EEV, but the incubation is often shorter for EEE compared with that of WEE.

Signalment

Unvaccinated adult horses and other equids (for VEE in donkeys see here) are at risk in areas with suitable vectors. Vaccinated horses can still develop the disease, particularly if they are young or old.

Clinical Signs

Worse in unvaccinated horses.[3] Neurological signs may be assymmetrical.[10]

EEE and WEE

Following an incubation period of up to 21days[3], an initial pyrexia and mild depression are short-lived and often missed. The acute phase of the disease presents with mild to severe pyrexia, anorexia and stiffness, lasting up to 5 days. During this time, the horse is viraemic and capable of amplifying the disease. The fever may then fluctuate with neurological derangements appearing a few days post-infection.[1] These changes indicate disease progression, which occurs more frequently with EEE (the most virulent of the three serotypes). Any of the following may be observed[3]:

- conscious proprioceptive deficits

- propulsive walking

- depression

- somnolence

- aggression

- excitability

- restlessness

- hypersensitivity to sound and touch

Worsening neurological deficits may result in[3]:

- head pressing

- head tilt

- ataxia

- circling

- apparent blindness

- facial and appendicular muscle fasciculations

- pendulous lower lip[1]

- pharynx, larynx and tongue paralysis

- seizures[1]

- recumbency for 1-7 days followed by death[1]

VEE

Clinical signs may resemble those of WEE and EEE or may vary[3]:

- pyrexia peaks early and persists throughout the disease course

- mild pyrexia and leukopenia with endemic strains

- severe pyrexia and leukopenia with epidemic strains

- neurological signs around 4 days post-infection

- diarrhoea, severe depression, recumbency and death may precede neurological signs

- other signs: abortion, oral ulceration, pulmonary haemorrhage, epistaxis

Diagnosis

Presumptive based on history, epidemiology and clinical signs.[1] Definitive diagnosis requires virus identification, serological tests and/or post-mortem examination.

Laboratory Tests

Virus Identification

Serology

Ab titre increases sharply within 24 hours of the initial viraemia, before clinical signs are apparent. It then deteriorates over 6 months. Samples taken when clinical signs appear are likely to miss the Ab peak and will demonstrate a decreasing titre. Thus, serological confirmation of Eastern or Western EEV infection requires a four-fold or greater increase[1] OR decrease in Ab titre in paired serum samples taken 10-14 days apart. A presumptive diagnosis can be made on a single sample if an unvaccinated horse with suggestive clinical signs has Ab against only Eastern or Western EEV. Colostral-derived Ab has a serum half-life of around 20days and may interfere with diagnosis in foals.[12]

- Complement fixation (CF): to avoid anti-complementary effects, serum should be separated from blood as soon as possible. CF Ab against both Eastern and Western EEV is less useful for serological diagnosis because it appears relatively late and does not persist.

- Haemagglutination inhibition (HAI): titres of 1/10 and 1/20 are indicative, titres of 1/40 and above are positive.

- ELISA may be used to detect viral-specific IgM to the surface glycoprotein of Venezuelan EEV, from 3 days post-onset of clinical signs up to 21 days post-infection. This is useful in acute infections where convalescent serum samples are unobtainable.

- The plaque reduction neutralization (PRN) test is very specific and can differentiate EEE and WEE infections. It is performed in duck embryo fibroblast, Vero, or BHK-21 cell cultures. Serum is tested against 100 plaque-forming units of virus. Endpoints are based on a 90% reduction in the number of plaques compared with the virus control.

Most commonly, the PRN test or a combination of PRN and HAI tests is used to detect Ab against Eastern and Western EEV. Cross-reactivity occurs between Ab against these viruses in the CF and HAI tests.

Clinical Pathology

CSF samples demonstrate increased cellularity (50-400 mononuclear cells/µl) and protein concentration (100-200mg/dl).[3]

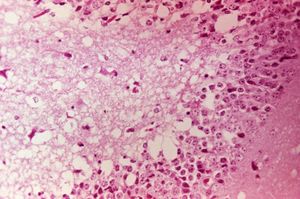

Post-mortem findings

PRECAUTION: infective viral particles may be present in CNS and other tissues. Gross pathological lesions of the brain and spinal cord are rarely seen in horses, although traumatic ecchymotic haemorrhages and vascular congestion of the CNS may be evident. The extent of microscopic lesions is dictated by the severity of infection and duration of neurological involvement.[13] Such lesions with or without immunohistochemistry may be diagnostic. The cerebral cortex, thalamus and hypothalamus are often severely affected. Mononuclear meningitis, neuronal degeneration, diffuse and focal gliosis and perivascular cuffing are also seen. Histological lesions of EEE are usually present throughout the CNS, with widespread and severe neutrophilic inflammation of the grey matter. Lesions caused by Western EEV infection are more focal and lymphocytic in nature. VEE cases often exhibit haemorrhage and liquefactive necrosis of the cerebral cortex, but lesions are not restricted to the CNS. In the pancreas, acinar cells atrophy and duct cells undergo hyperplasia. There may also be damage to the liver and heart.

Differential diagnoses[3]

- Other togaviral encephalitides

- Other viral encephalitides

- Trauma

- Equine herpesvirus 1 infection

- Hepatic encephalopathy

- Rabies

- Botulism

- Leukoencephalomalacia

- Bacterial meningoencephalitis

- Equine protozoal myeloencephalitis (EPM)

- Verminous encephalomyelitis

- West Nile Virus (WNV) infection

- Toxicosis

Treatment[3]

No effective, specific treatment is available.[1] Supportive management includes:

- NSAIDs (phenylbutazone, flunixin meglumine) to control pyrexia, inflammation and discomfort

- DMSO IV in a 20% solution to control inflamation, provide some analgesia and mild sedation

- Pentobarbital, diazepam IV, phenobarbital PO or phenytoin IV to control seizures

- Antibiotic therapy in cases with secondary bacterial infection

- Balanced fluid solutions IV or PO as necessary to correct hydration status

- Dietary supplementation (enteral, or parenteral if anorexia persists more than 48 hours)

- Laxatives to reduce the risk of impaction

- Protection of body regions susceptible to self-induced trauma and provision of deep bedding

- Sling support for recumbent horses

Prognosis

Comatose animals rarely survive. Survivors exhibit functional improvement over weeks to months, but complete recovery from neurological deficits is rare[14] Residual ataxia, depression and abnormal behaviour is often seen with EEE, but less so with WEE. The mortality rates for neurological equine viral encephalitis are reportedly:

- EEE 75-100%

- WEE 20-50%

- VEE 40-80%

It is generally assumed that infection does not provide protective immunity, however, protection for up to 2 years has been noted.[3]

Control

Vaccination

Most vaccines are killed (produced in cell culture and inactivated with formalin) and elicit significant increases in Ab titre after 3 days. Protective titres last for 6-8 months.[3] Some cross-protection is seen between the serotypes but not between Western and Eastern EEV. Monovalent, divalent and trivalent vaccines are available but the response to monovalent VEE vaccination is decreased in horses previously vaccinated against WEE and EEE. The current recommendation is to vaccinate susceptible horses annually in late spring or several months before the high risk season. Biannual or triannual vaccination should be employed in regions where the vector season is prolonged. Susceptible horses should also be vaccinated in the face of an outbreak. Mares should be vaccinated one month prior to foaling to boost colostral-derived Ab[10], which persists for 6-7 months.[12] Although foals can be vaccinated at any time, early vaccination should be followed by boosters at 6 months and at one year. Vaccination does not interfere with the ELISA assay for VEE.[3]PRECAUTION: human vaccination is recommended for vets in endemic areas.

Vector control

Responsible use of insecticides and repellents[1], elimination of standing water, and stable screening will all help to reduce viral transmission. Environmental application of insecticides may be useful in endemic areas or during an outbreak.[3] Horses infected with Venezuelan EEV should be isolated for 3 weeks after complete recovery.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Pasquini, C, Pasquini S, Woods, P (2005)Volume 1: Guide to Equine Clinics, third edition, p266, SUDZ publishing.

- ↑ Karsted, L, Hansen, R.P (1959) Natural and experimental infections in swine with the virus of eastern equine encephalomyelitis, J Infect Dis 105:293-296. In: Bertone, J.J (2010) Viral Encephalitis in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 Bertone, J.J (2010) Viral Encephalitis in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12

- ↑ Pursell, A.R, Mitchell, F.E, Seibold, H.R (1976) Naturally occurring and experimentally induced eastern encephalomyelitis in calves, J Am Vet Med Assoc, 169:1101-1103. In: Bertone, J.J (2010) Viral Encephalitis in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12

- ↑ Steele, K.E, Twenhafel, N.A (2010) Review Paper: Pathology of Animal Models of Alphavirus Encephalitis. Vet Pathol. Jun 15. [Epub ahead of print].

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 http://www.defra.gov.uk/foodfarm/farmanimal/diseases/atoz/viralenceph/index.htm, accessed July 2010

- ↑ McLintock, J (1980) The arbovirus problem in Canada, Can J Public Health, 67(Suppl 1):8-12. In: Bertone, J.J (2010) Viral Encephalitis in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12

- ↑ Karabatsos, N, Lewis, A.L, Calisher, C.H, Hunt, A.R, and Roehrig, J.T (1988). Identification of Highland J virus from a Florida horse. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 39, 603-606. In: Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals found at http://www.oie.int/eng/normes/mmanual/A_00081.htm, accessed July 2010.

- ↑ Kissling, R.E, Chamberlain, R.W (1967) Venezuelan equine encephalitis, Adv Vet Sci Comp Med, 11:65-84. In: Bertone, J.J (2010) Viral Encephalitis in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Merck & Co (2008) The Merck Veterinary Manual (Eighth Edition), Merial found at http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/100900.htm&word=Equine%2cencephalitis, accessed July 2010

- ↑ Sellers, R.F (1980) Weather, host and vector: their interplay in the spread of insect-borne animal virus diseases, J Hyg (Lond), 85:65-102. In: Bertone, J.J (2010) Viral Encephalitis in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Ferguson, J.A, Reeves, W.C, Hardy, J.L (1979) Studies on immunity to alphaviruses in foals, Am J Vet Res, 40:5-10. In: Bertone, J.J (2010) Viral Encephalitis in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12

- ↑ Walton T.E (1981) Venezuelan, eastern, and western encephalomyelitis. In: Virus Diseases of Food Animals. A World Geography of Epidemiology and Control. Disease Monographs, Vol. 2, Gibbs E.P.J, ed. Academic Press, New York, USA, 587-625.

- ↑ Patterson, J.S, Maes, R.K, Mullaney, T.P, Benson, C.L (1996) Immunohistochemical diagnosis of eastern equine encephalomyelitis, J Vet Diagn Invest, 8(2):156-160. In: Bertone, J.J (2010) Viral Encephalitis in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12

| Also known as: | Alphaviral encephalitis, Alphaviral encephalitides Eastern equine encephalitis, Eastern equine encephalomyelitis, EEE |