| This article is still under construction. |

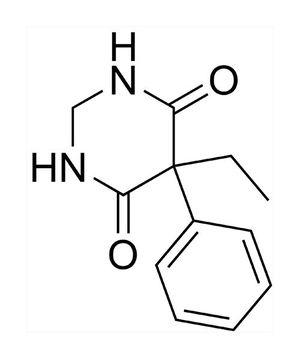

Primidone is a barbiturate derivative that is closely related to phenobarbital. It is a colourless, tasteless substance that forms crystals and is metabolised to the active metabolites phenobarbital and phenylethylmalonamide (PEMA). Primidone is widely used in veterinary medicine for the control of epileptiform seizures, but does not appear to have an advantage over phenobarbital despite its greater potential to cause hepatotoxicity. However, it appears that certain individuals may respond more favourably to primidone than phenobarbital.

Mechanism of Action

Barbituates act by depressing the central nervous system (CNS) by acting at the Gamma Aminobutyric Acid A receptors (GABAa). They mimic and enhance GABA, which is the principle inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS. Once bound to the GABAa receptor they reduce the rate of GABA dissocation and thereby increase chloride conductance. This results in hyperpolarisation of the membrane and reduced neuronal excitability, giving a sedative effect. However, as the concentration of barbituate increases, it starts to have a direct effect on the chloride conductance and this is thought to bring about the anaesthetic effects. Barbiturates depress the motor centres, conferring anticonvulsant activity, and the sensory centres, inducing anaesthesia.

Pharmacologic Considerations

In humans, approximately 60-90% of an oral does of primidone is rapidly absorbed from the GI tract, with a peak serum level being obtained in about 3 hours. in animals, primidone is oxidised to phenobarbital and cleaved to PEMA (C2). Although all three compounds have anticonvulsant activity, most of primidone's anticonvulsant activity in dogs results from phenobarbital: as the compounf with the longest half-life, it accumulates to the highest concentrations. The potency of primidone and PEMA is 1/30 that of phenobarbital. The efficacy of primidone generally is equal to or less that that or phenobarbital, and anticonvulsant acitivity can be correlated to serum phenobarbital levels. Because of this relationship. serum phenobarbital concentrats can and should be used to guide design of primidone dosing regimens. Target therapetic ranges are teh same as for phenobarbital. Primidone continues to be used in patients which have proven refractory to phenobarbital at the maximum therapeutic drug concentration. Note that its efficacy in the scenario has not been proven. efficacy may simply reflect improced conversion to phenobarbital (i.e. animals that are induced may metabolise the drug to greater concentrations of phenobarbital that those generated from administration of phenobarbital alone). There is no advantage in useing primisone rather than phenobarbital for control of epilepsy in most dogs. Primidone is more toxin in cats and rabis. cats metabolise primidone to phenobarbital to a lesser extent than dogs - less effective, more toxic.

Although seizures can be controlled with primidone in dogs, primidone has little advantage over phenobarbital in dogs. Control of seizures ion dogs is correlated with the plasma concentration of phenobarbital rather than primidone. In a comparison between primidone and phenobarbital. there was no significant difference between phenobarbital and primidone with respect to seizure control, and primidone appeared more likely to induce liver injury than phenobarbital. The authors conluded that phenobarbital, rather than primidone, should be the drug of first choice for treatment of canine epilepsy. However, there may be rare cases that respons to primodone when phenobarbital alone has not been effective (1 out f 15). primodone is more expensive than phenobarbital but is not classifies as a controlled drug in the US and therefore does not require the same degree of record keeping.

I

Dosage

nitial dosages in dogs are 3-5mg/kg q8-12h but have been increased up to 12mg/kg q8h. If one is converting a patient from primidone to phenobarbital or vice versa, the conversion is 65mg phenobarbital to 250mg primidone.

Side Effects and Contraindications

Since a large proportion of primidone is converted to phenobarbital, most adverse and side affects are the same as for this drug. These may include polyphagia, polyuria and polydipsia, which are usually transient and disappear with time. A sedative effect may also be seen. Additional side effects of primidone are nausea, drowsiness, ataxia, nystagmus and, rarely, dermatitis. In many, megaloblastic anaemia may develop from primidone use, and so the drug should be stored securely out of the reacch of children.

Primidone is associated with a higher incidence of hepatotoxicity than phenobarbital: hepatic necrosis, fibrosis and cirrhosis have all been associated with chronic use of primidone. One study reported that up to 14 in 20 dogs develop liver toxicity following primidone administration. It is therefore important that liver enzyme assays and tests of liver function are regularly performed to monitor toxicity when primidone is prescribed to veterinary patients.

Primidone should bot be used in combination with chloramphenicol, as chloramphenicol is a potent inhibioty of microsomal enzymes and so may lead to primidone toxicity. signs include severe central nervous system depression, and inappetance. Primidone has also been reported to cause intrahepatic cholestasis when used in combination with phenytoin.

Manufacturers do not recommed the use of primidone in cats, although studies have suggested that primidone is probably safe in this species.

References

- Riviere, J E and Papich, M G (2009) Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Wiley.

- Adams, R H (2001) Veterinary pharmacology and therapeutics, Wiley-Blackwell.

- NOAH (2010) Compendium of Data Sheets for Animal Medicines.