Introduction

Infections of Theileria equi and Babesia caballi, either individually or together, may occur in the donkey. These equine-specific protozoa are tick-transmitted, and are present throughout parts of the world where the appropriate type of tick vectors live. Babesiosis is endemic in equines in many parts of the world. Within Europe, it is considered to be endemic in horses in the South of France and central and southern Italy. Equine cases are reported sporadically, with both clinical and non-clinical manifestations in other European countries.

Seroprevalence of babesia is often related to the level of tick activity and tick numbers (Sahibi, 1994). Management practices may contribute to greater tick infestation in donkeys compared to horses.

Clinical features

T. equi is generally regarded as the more pathogenic of the two species. In the horse, acute disease involves fever, anaemia, colic, haemoglobinuria and jaundice. The chronic form may or may not follow the acute form. Signs are generally less specific, leading to loss of condition and poor exercise tolerance.

Young animals are less susceptible to babesia than older animals and so, by being infected at a young age, a donkey foal may develop a resistance to clinical disease and not exhibit signs when infected with the protozoa when older. Stress factors, concurrent disease and reintroduction to an infected area after a period of absence can precipitate the disease.

The acute disease is less frequently seen in the donkey compared to the horse, and chronic cases only become apparent if the animal is overworked, stressed or immuno-suppressed. Gebreab (1997), in a study conducted in Ethiopia, observed clinical disease in 30% of infected equines, the majority of which were donkeys. The signs observed in this group included congested mucous membrane, lacrimation, depression and fever.

Diagnosis

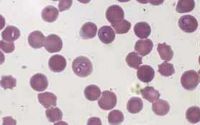

- Geimsa - stained thick or thin blood smear taken from a peripheral blood vessel

- Serological tests

Treatment

- Supportive and symptomatic treatment

- Imidiocarb dipropionate may be used to treat clinical cases. Note that imidiocarb has not been fully evaluated for use in donkeys. In horses T. equi is usually more refractive to treatment. Here, higher doses of imidiocarb that approach the LD50 maybe required and hence side effects become more common (Anon, 1998). Donkeys may even die if given high doses of imidiocarb

- Amicarbalide and diminazene have also been used in horses

Control

Measures implemented depend on whether babesiosis is endemic or not.

They include:

- Restrictions on imports of animals to an area

- Tick control

- Care to avoid iatrogenic spread via contaminated needles and surgical equipment

No vaccine is presently available to prevent piroplasmosis. As with many latent or carrier infections, use of immunosuppressive drugs could possibly lead to expression of the pathogen and great care should be exercised in using such medicines when babesia may also be present (Oladosu, 1988).

Literature Search

Use these links to find recent scientific publications via CAB Abstracts (log in required unless accessing from a subscribing organisation).

Piroplasmosis in donkeys publications

References

- Anzuino, J. (2008) Exotic infections In Svendsen, E.D., Duncan, J. and Hadrill, D. (2008) The Professional Handbook of the Donkey, 4th edition, Whittet Books, Chapter 14

|

|

This section was sponsored and content provided by THE DONKEY SANCTUARY |

|---|