Equine Protozoal Myeloencephalitis

| This article is still under construction. |

| Also known as: | EPM Equine protozoal myelitis |

Description

A progressive, infectious,[1]neurological disease of horses, endemic in the USA[2] and only encountered elsewhere in imported equids.[3] EPM is one of the most frequently diagnosed neurological conditions of the Western Hemisphere[4] and the principal differential for multifocal, asymmetric progressive central nervous system (CNS) disease.[1] As it can resemble any neurological disorder, EPM must be considered in any horse with neurological signs if it resides in the Americas or if it has been imported from that area[2][5] The disease is not contagious.[1]

Aetiology

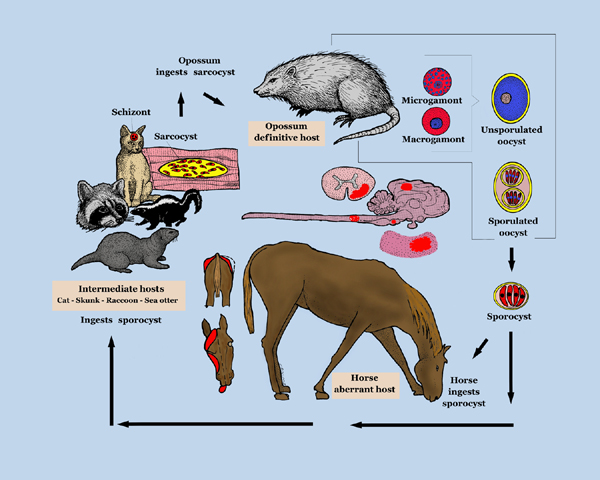

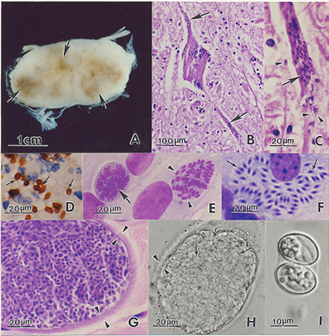

EPM results from infection of the CNS by the apicomplexan parasite Sarcocystis neurona or, less frequently, its close relative Neospora hughesi.[6][7] These protozoans develop within neurons[4] causing immediate or inflammatory-mediated neuronal damage. The organisms migrate randomly through the brain and spinal cord causing asymmetrical lesions of grey and white matter and thus multifocal lower and upper motor neuron deficits.[1]

Signalment

Mostly Standardbreds and Thoroughbreds aged 1-6years.[1] Foal infection may be possible.[2]

Differential Diagnoses

The protozoan can migrate to any region of the CNS[2], thus the differential list comprises almost all diseases of this system.[4]

| Differential | Differentiating signs | Tests to rule out |

| Cervical vertebral malformation (CVM, cervical compressive myelopathy, cervical vertebral instability, cervical spondylomyelopathy, Wobbler's syndrome) | Symmetrical gait deficits, worse in pelvic limbs[8] with spasticity and dysmetria, good retention of strength, no muscle wasting (Furr) NB:can be concurrent with EPM (Hahn) | Standing plain lateral rads of C1 to T1 (Hahn in Furr) |

| WNV encephalitis | Systemically ill, pyrexia and changes in leukogram | CSF abnormal, difficult if horse not febrile and no excessive muscle fasciculations, IgM capture ELISA |

| EEE | Systemically ill, pyrexia and changes in leukogram, abnormal motor function (Long), rapidly progressive (seino, p134) | CSF abnormal |

| WEE | Systemically ill, pyrexia and changes in leukogram, abnormal motor function (Long) | |

| VEE | Systemically ill, pyrexia and changes in leukogram | IgM ELISA (Bertone) |

| Equine herpesvirus-1 myeloencephalopathy | Sudden onset and early stabilization of neuro signs, multiple horses affected, recent fever, abortion (14 in Wilson and Pusterla p615) dysuria not often seen in EPM | PCR (Furr) |

| Rabies | Rapid progression (Sommardahl), behavioural alterations, depression, seizure, coma (Long) | Post-mortem dx (Sommardahl) |

| Polyneuritis equi | Cranial nerve deficits peripheral with no change in attitude (6 p623 in Saville) | Western blot analysis of CSF(20 p623 in Saville) |

| Equine degenerative myeloencephalopathy | Symmetrical signs (Nout, p606) | May get increased CSF CK (3 in Nout p608) and reduced serum Vitamin E concentrations but unreliable ante mortem dx |

| Verminous encephalomyelitis | Acute onset | CSF analysis(Jose-Cunilleras) |

| Bacterial meningoencephalitis | Stiff neck (Pasq) | |

| CNS abscessation (Furr) | ||

| Spinal trauma(Pasq) | Hx (usually acute onest nuero signs), usually spolitary lesion loclaised by neuro exa (71 p589) | Rads, myelography, CT, MRI, nuclear scintigraphy, CSF analysis, nerve conduction velocities, EMG, transcranial magnetic stimulation (p590) |

| Occipito-atlanto-axial malformation | Deficits develop before 6mths (7,12, Seino) | |

| Spinal tumors | CT, MRI, definitive dx requires cytology, biopsy, histopathology, CSF analysis (Sellon) | |

| Sorghum cystitis/ataxia (Pasq) | Posterior ataxia or paresis, cystitis, hx of grazing Sorghum species (Talcott, ch22 |

Cauda equina neuritis

Prognosis

Depends on duration and severity of neurological signs[3] but clinical resolution is more likely if the condition is diagnosed and treated early.[2] With standard therapy, involving 6-8months of ponazuzril or pyrimethamine-sulfadiazine (V), there is a recovery rate of around 25% and an improvement in 60-75% of cases.[9] A good prognosis might be expected if there is an improvement in clinical signs within two weeks of commencing anti-protozoal and anti-inflammatory treatment (V). The prognosis will be guarded to poor[1] for a horse with severe irreversible neuronal damage or one that has not been diagnosed or treated appropriately (V).

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Pasquini, C, Pasquini, S, Woods, P (2005) Guide to Equine Clinics Volume 1: Equine Medicine (Third edition), SUDZ Publishing, 245-250. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Pasq" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "Pasq" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "Pasq" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "Pasq" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Gray, L.C, Magdesian, K.G, Sturges, B.K, Madigan, J.E (2001) Suspected protozoal myeloencephalitis in a two-month-old colt. Vet Rec, 149:269-273. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "EPM8" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 3.0 3.1 Vatistas, N, Mayhew, J (1995) Differential diagnosis of polyneuritis equi. In Practice, Jan, 26-29.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Furr, M (2010) Equine protozoal myeloencephalitis in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.

- ↑ DEFRA, The Animal Health Trust, The British Equine Veterinary Association (2009) Surveillance: Equine disease surveillance, April to June 2009, The Vet Rec, Oct 24:489-492.

- ↑ Dubey, J.P, Lindsay, D.S, Saville, W.J, Reed, S.M, Granstrom, D.E, Speer, C.A (2001)A review of Sarcocystis neurona and equine protozoal myeloencephalitis (EPM). Vet Parasitol, 95:89-131. In: Pusterla, N, Wilson, W.D, Conrad, P.A, Barr, B.C, Ferraro, G.L, Daft, B.M, Leutenegger, C.M (2006) Cytokine gene signatures in neural tissue of horses with equine protozoal myeloencephalitis or equine herpes type 1 myeloencephalopathy. Vet Rec, Sep 9:Papers & Articles.

- ↑ Wobeser, B.K, Godson, D.L, Rejmanek, D, Dowling, P (2009) Equine protozoal myeloencephalitis caused by Neospora hughesi in an adult horse in Saskatchewan. Can Vet J, 50(8):851-3.

- ↑ Mayhew, I.G, deLahunta, A, Whitlock, R.H, Krook, L, Tasker, J.B (1978) Spinal cord disease in the horse, Cornell Vet, 68(Suppl 8):110-120. In: Hahn, C.N (2010) Cervical Vertebral Malformation in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.

- ↑ MacKay, R.J (2006) Equine protozoa myeloencephalitis: treatment, prognosis and prevention. Clin Tech Equine Pract, 5:9-16. In: Furr, M (2010) Equine protozoal myeloencephalitis in Reed, S.M, Bayly, W.M. and Sellon, D.C (2010) Equine Internal Medicine (Third Edition), Saunders, Chapter 12.