Flea Allergic Dermatitis

| This article is still under construction. |

| Also known as: | FAD, Flea Allergy Dermatitis, Flea Bite Hypersensitivity, FBH, Flea Dermatosis |

Description

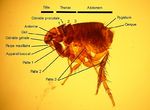

Flea allergic dermatitis is the most common skin disease of dogs and cats worldwide. Cases are caused by flea infestation, mainly by Ctenocephalides felis, the cat flea, but Ctenocephalides canis, Archaeopsylla erinacei, Spylopsyllus cuniculi and Pulex irritans can also be found on cats and dogs. Fleas are blood sucking, wingless insects that live and breed in the hair coat of an animal and often cause pruritis and annoyance. The term flea allergic dermatitis refers to the condition that arises due to hypersensitivity to flea saliva when a flea bites. Flea saliva also contains irritant components that contribute to the disease.

Signalment

Dogs and cats of any age or sex may be afflicted by flea allergic dermatitis.

Diagnosis

Clinical Signs

In dogs, flea allergic dermatitis usually causes marked pruritus, although individual variation does exist. Lesions are most typically seen on the caudal dorsum, the inner and posterior thighs and the umbilical area , but any region may be affected. Within fifteen minutes of receiving a flea bite a papule appears and persits for up to 72 hours, when it forms a crust. However, these lesions may be difficult to appreciate due to the secondary changes that result from self-trauma in response to pruritus. These may include excoriations, erythema, seborrhoea, hyperpigmentation and lichenification. A mild secondary bacterial folliculitis may also be present.

Cats respond to most cutaneous insults in one of four reactions patterns (miliary dermatitis, eosinophilic granuloma complex, head and neck pruritus, symmetrical alopecia). This is also true in flea infestation and flea allergic dermatitis. Miliary dermatitis is by far the most common presentation in this case, but symmetrical alopecia and eosinophilic granuloma complex may also be seen.

Additional Tests

If clinical signs are suggestive of flea allergic dermatitis, demonstration of the presence of fleas or flea faeces will help confirm the diagnosis. Parting the hair and visually inspecting for fleas may be sufficient for this; alternatively a flea comb can be used. Material obtained by combing may be placed on a moistened, light-coloured paper- brown material will "bleed" on the paper if it is indeed flea faeces.

If doubt still remains over the diagnosis of flea allergic dermatitis, the response to a flea control programme will help rule the diagnosis out or in.

Pathology

Grossly, papular dermatitis is seen in combination with any of crusting, erythema, alopecia, excoriations, hyperpigmentation or lichenification. Microscopically, flea allergic dermatitis presents as a hyperplastic superficial perivascular dermatitis. Oedema may be seen, together with an influx of mast cells, eosinophils, lymphocytes and histiocytes.

Treatment

Treatment of flea allergic dermatitis is by appropriate flea control.

To implement an effective flea control programme, it is important to understand the flea life cycle. After a flea takes a blood meal from a pet, mating and egg production occurs within two to three days. The small, white eggs produced are laid on the host but fall to the ground where they hatch to larvae. Insect development inhibitors may act on eggs for a period after laying, and insecticides can affect hatchability.

Hatching normally occurs within three weeks of laying depending on environmental temperature and humidity. Flea larvae feed on the faeces of adult fleas, and undergo two moults before pupating. Generally, the pupal stage lasts around ten days, but it is possible for the pupa to survive for up to a year within its cocoon. This cocoon is resistant to parasitacidal agents, as well as dessication and freezing. Warmth, vibrations and carbon dioxide indicate the presence of a suitable host to the pupated flea, stimulating the emergence of the adult. The adult flea is then drawn to the host by heat and carbon dioxide, as well as the individual "attractiveness" of the host.

There are therfore two main aims of flea control:

- To kill adult fleas from the affected animal, and

- To eliminate the reservoir of eggs and immature fleas in the environment, thus preventing re-infestation.

Although flea repellents and mechanical methods of removing fleas are available, the most effective way to achieve flea control is by the use of chemicals that will kill adults, larvae or eggs. There are several products available to kill adult fleas on the host which are safe and effective. These include fipronil, imidacloprid and selemectin, which should be used on a regular basis in accordance with instructions in order to give ongoing control of adults. Choice of product may be influenced by route of administration, mechanism of action, duration of effects and efficacy.

There are two main groups of products that act on life stages free living in the environment. Juvenile hormone analogues, such as methoprene and pyriproxifen, disrupt thte normal sequential activation of genes necessary to direct the development of successive stages of the flea life cycle. These products are also ovicidal. Insect development inhibitors, such as lufenuron and cyromazine, interfere with chitin synthesis. Lufenuron prevents the synthesis of chitin to interupt embryogenesis, hatching and moulting, whereas cryomazine stiffens chitin to prevent expansion with flea growth. Use of chemicals these chemicals in combination with those controlling the adult flea population on the host gives complete flea control.

If pruritus is severe, it may be necessary to treat the affected animal symptomatically as well as controlling its fleas. A short course of glucocorticoids, e.g. prednisolone, can be used for this purpose.

Prognosis

If flea control is implemented correctly, and the client and patient are compliant, prognosis is excellent.

References

- Thoday, K (1981) Skin diseases of the cat. In Practice, 3(6), 22-35.

- Nuttall, T (2001) Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of atopic dermatitis. In Practice, 23(8), 442-452.

- Perrins and Hendricks (2007) Recent advances in flea control. In Practice, 29(4), 202-207.