Toxoplasmosis - Cat and Dog

Description

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate, intracellular coccidian parasite that is capable of infecting most mammals including man. Cats and other Felidae are the definitive host for T. gondii, and all other mammals are intermediate hosts. Toxoplasma gondii has three infectious stages: 1) sporozoites; 2) an actively reproducing stage called tachyzoites; and 3) slowly multiplying bradyzoites. Tachyzoites and bradyzoites are found in tissue cysts, whereas sporozoites are containted within oocysts, which are excreted in the faeces. This means that the protozoa can be transmitted by ingestion of oocyst-contaminated food or water, or by consumption of infected tissue. Transplacental infection is also possible.

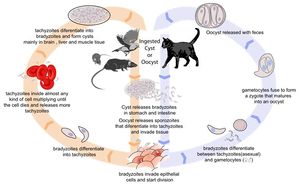

Life Cycle

In the naive definitive host, Toxoplasma gondii undergoes an enteroepithelial life cycle. Cats become infected by ingesting intermediate hosts containing tissue cysts, which release their bradyzoites in the gastrointestinal tract when the wall is digested. Bradyzoites then penetrate the small intestinal epithelium and produce five types of schizonts, which then give rise to merozoites. Male and female gamonts are formed from merozoites, which fertilise to form a macrogamont. A wall forms aroung the macrogamont to produce an oocyst, which is passed in the faeces approximately three days after ingestion of the tissue cyst. Initially, these oocysts are unsporulated and are therefore not infectious, but after 1 to 5 days sporulation occurs to produce two sporocysts, each with four infectious sporozoites. This sporulation is dependent on temperature and aeration, and sporocysts can remain viable in the environment for up to 18 months even if exposed to high or freezing temperatures and low humidity. As cats generally develop immunity to T. gondii after the initial infection, they will only shed oocysts once in their lifetime.

When other, non-feline, carnivores (such as dogs) consume tissue cysts or oocysts from cat faeces, Toxoplasma gondii initiates extraintestinal replication. This process is the same for all hosts, and does not vary with the form of the parasite ingested. Bradyzoites and sporozoites, from cysts and oocysts respectively, are released in the intestine and infect the intestinal epithelium where they replicate. This produces tachyzoites, which are lunate in shape, about 6 microns in diameter and possess the ability to multiply in almost any cell type. The infected cell ruptures to release tachyzoites which then disseminate via blood and lymph to infect other tissues. Tachyzoites then replicate intracellularly and, if the cell does not burst, they eventually encyst and persist for the life of the host. Tissue cysts readily form in the CNS, muscles and visceral organs.

Transmission

Any of the three life stages of T gondii can infect warmblooded vertebrates, including cats and humans. Since tachyzoites are readily inactivated by gastric secretions, most orally acquired infections develop following the ingestion of bradyzoites or sporozoites. Coprophagy is uncommon in cats; the usual source of infection is the ingestion of T gondii bradyzoites during carnivorous feeding. Oocysts can generally be detected in the faeces from three days post-infection (see graph on the right) and oocyst shedding is usually completed by 10 to 21 days post-infection. Only 20 per cent of cats infected by ingestion of sporulated oocysts will shed the organism; the onset of oocyst shedding is between 18 and 44 days post-infection, and the patent period is six to 10 days (Dubey and Lappin 1998). Transplacental infection occurs if a T gondii-naive woman or queen ingests T gondii during gestation. First trimester infections are rare but, when they occur, the sequelae are generally severe. In humans, stillbirth, abortion and severe CNS disease are common. In neonatally infected kittens, interstitial pneumonia, necrotising hepatitis, myocarditis, non-suppurative encephalitis and uveitis are commonly detected after necropsy and histological examination. In humans, the fetus is more likely to be infected if exposed during the second and third trimesters but the resultant disease is usually milder. The same may be true for cats. Previously infected women or queens are unlikely to transmit T gondii to the fetus, even if exposed during gestation.

Pathogenesis

Signalment

Diagnosis

Clinical Signs

The tachyzoite is the stage responsible for tissue damage; therefore, clinical signs depend on the number of tachyzoites released, the ability of the host immune system to limit tachyzoite spread, and the organs damaged by the tachyzoites. Because adult immunocompetent animals control tachyzoite spread efficiently, toxoplasmosis is usually a subclinical illness. However, in young animals, particularly puppies, kittens, and piglets, tachyzoites spread systemically and cause interstitial pneumonia, myocarditis, hepatic necrosis, meningoencephalomyelitis, chorioretinitis, lymphadenopathy, and myositis. The corresponding clinical signs include fever, diarrhea, cough, dyspnea, icterus, seizures, and death. T gondii is also an important cause of abortion and stillbirth in sheep and goats and sometimes in pigs. After infection of a pregnant ewe, tachyzoites spread via the bloodstream to placental cotyledons, causing necrosis. Tachyzoites may also spread to the fetus, causing necrosis in multiple organs. Finally, immunocompromised adult animals (eg, cats infected with feline immunodeficiency virus) are extremely susceptible to developing acute generalized toxoplasmosis.

Laboratory Tests

- Serology

- Sabin-Feldman Dye test (old method)

- ELISA

- Mouse inoculation for confirmation

- 30-80% test seropositive

- Each cat sheds oocysts for 1-2 weeks of its life

Diagnosis is made by biologic, serologic, or histologic methods, or by some combination of the above. Clinical signs of toxoplasmosis are nonspecific and are not sufficiently characteristic for a definite diagnosis. Antemortem diagnosis may be accomplished by indirect hemagglutination assay, indirect fluorescent antibody assay, latex agglutination test, or ELISA. IgM antibodies appear sooner after infection than IgG antibodies but generally do not persist past 3 mo after infection. Increased IgM titers (>1:256) are consistent with recent infection. In contrast, IgG antibodies appear by the fourth week after infection and may remain increased for years during subclinical infection. To be useful, IgG titers must be measured in paired sera from the acute and convalescent stages (3-4 wk apart) and must show at least a 4-fold increase in titer. Additionally, CSF and aqueous humor may be analyzed for the presence of tachyzoites or anti- T gondii antibodies. Postmortem, tachyzoites may be seen in tissue impression smears. Additionally, microscopic examination of tissue sections may reveal the presence of tachyzoites or bradyzoites. T gondii is morphologically similar to other protozoan parasites and must be differentiated from Sarcocystis spp (in cattle), S neurona (in horses), and Neospora caninum (in dogs).

Diagnostic Imaging

Pathology

Treatment

Prevention

- Cat

- Impossible if cat is allowed outdoors due to hunting

- If kept indoors, only canned food should be fed and vermin controlled

- ELISA to check if seropositive

For animals other than humans, treatment is seldom warranted. Sulfadiazine (15-25 mg/kg) and pyrimethamine (0.44 mg/kg) act synergistically and are widely used for treatment of toxoplasmosis. While these drugs are beneficial if given in the acute stage of the disease when there is active multiplication of the parasite, they will not usually eradicate infection. These drugs are believed to have little effect on the bradyzoite stage. Certain other drugs, including diaminodiphenylsulfone, atovaquone, and spiramycin are also used to treat toxoplasmosis in difficult cases. Clindamycin is the treatment of choice for dogs and cats, at 10-40 mg/kg and 25-50 mg/kg respectively, for 14-21 days.

Zoonosis

T gondii is an important zoonotic agent. In some areas of the world, up to 60% of the human population have serum IgG titers to T gondii and are likely to be persistently infected. Toxoplasmosis is a major concern for people with immune system dysfunction (eg, people infected with human immunodeficiency virus). In these individuals, toxoplasmosis usually presents as meningoencephalitis and results from the emergence of T gondii from tissue cysts located in the brain as immunity wanes rather than from primary T gondii infection. Toxoplasmosis is also a major concern for pregnant women because tachyzoites can migrate transplacentally and cause birth defects in human fetuses. Infection of women with T gondii may occur after ingestion of undercooked meat or accidental ingestion of oocysts from cat feces. To prevent infection, the hands of people handling meat should be washed thoroughly with soap and water after contact, as should all cutting boards, sink tops, knives, and other materials. The stages of T gondii in meat are killed by contact with soap and water. T gondii organisms in meat can also be killed by exposure to extreme cold or heat. Tissue cysts in meat are killed by heating the meat throughout to 67°C or by cooling to -13°C. Toxoplasma in tissue cysts are also killed by exposure to 0.5 kilorads of gamma irradiation. Meat of any animal should be cooked to 67°C before consumption, and tasting meat while cooking or while seasoning should be avoided. Pregnant women should avoid contact with cat litter, soil, and raw meat. Pet cats should be fed only dry, canned, or cooked food. The cat litter box should be emptied daily, preferably not by a pregnant woman. Gloves should be worn while gardening. Vegetables should be washed thoroughly before eating because they may have been contaminated with cat feces.

At present there is no vaccine to prevent toxoplasmosis in humans.

Prognosis

Links

- Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine Toxoplasmosis Factsheet

- Feline Advisory Bureau: Toxoplasmosis in cats and man

- The Merck Veterinary Manual - Toxoplasmosis

References

- Dubey, J P (2005) Toxoplasmosis in cats and dogs. Proceedings of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association 2005.

- Lappin, M (1999) Feline toxoplasmosis. In Practice, 21(10), 578-589.

- Tilley, L.P. and Smith, F.W.K.(2004)The 5-minute Veterinary Consult (Fourth Edition) Blackwell Publishing.

- Merck & Co (2008) The Merck Veterinary Manual (Eighth Edition) Merial