Housesoiling - Cat

Introduction

House soiling is the commonest behavioural problem reported by cat owners [1][2]. House soiling is an umbrella term for problems in which urine or faeces are deposited inappropriately in the home, with two sub categories of problem being inappropriate elimination and indoor marking behaviour. It is important to differentiate between these problems as they require differing types of treatment. Since they often relate to an underlying cause due to fear or anxiety, inappropriate elimination and indoor marking can occur concurrently. Underlying medical conditions must also be ruled out before a behavioural diagnosis is considered.

Medical Assessment

Medical factors are very important in housesoiling and marking problems. Medical problems can underlie and cause behavioural problems, or they can contribute to them (see box). For example, conditions causing PU/PD can cause an indoor elimination problem by increasing the urgency to urinate in a cat that has problems accessing a latrine quickly, or it can contribute to an increase the frequency of indoor elimination in a cat that already has a behavioural problem.

| Medical factors underlying housesoiling problems |

|---|

| Conditions causing PU/PD: renal insufficiency, diabetes mellitus. |

| Feline lower urinary tract disease. |

| Diseases causing debilitation: osteoarthritis, senile dementia, and sensory loss. |

| Diseases affecting cognition: cognitive dysfunction syndrome, CNS pathology (primary or secondary to systemic disease). |

Any condition which affects gastrointestinal or urinary tract function is a potential candidate for involvement in cases of inappropriate elimination and a full medical examination is therefore essential. Any medical condition which alters the cat’s mobility or cognition may limit its ability to gain access to latrines or disrupt established elimination routines and housetraining. Organic disease may also be a factor in cases of undesirable marking behaviour.

The medical workup must include:

- Medical history.

- Clinical examination – including abdominal palpation.

- Urinalysis.

- Assessment of mobility, cognitive function and sensory perception.

- Further investigation through haematology, biochemistry or imaging techniques, as required.

Behavioural Assessment

It may be difficult in some cases to differentiate between Inappropriate elimination and indoor marking behaviour, and in some cases these two problems may occur together. It is important to collect all of the information needed to make a judgement:

- Age of onset.

- Previous record of house training.

- Pattern of deposits – location, frequency, volume.

- Orientation of deposits – onto vertical or horizontal surfaces.

- Posture and behaviour of the cat during deposition.

- Relationships between animals in the household.

- Presence or absence of the owner or other animals around the time of soiling (including other cats seen outside).

- Owner’s reaction to the deposits.

- Events in the household or the neighbourhood coinciding with the onset of the behaviour.

- Assessment of the cat’s emotional reactions to novelty in the environment and to strangers.

- Assessment of the environment: quality and location of resources, including latrine sites such as litter trays.

Using a House Plan

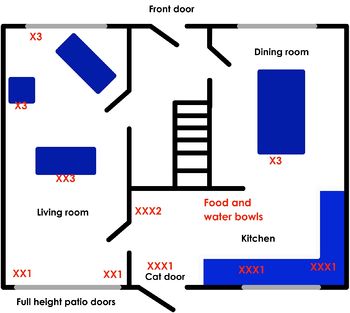

Owners should be asked to draw a floor plan of the house, indicating when and where urine and faces have been discovered. The owner should mark onto this diagram the location of urine and faeces that they have found, as well as the location of major resources (food and water locations, litter trays, cat doors), and the position of doors and windows (see figure). This can be annotated during the consultation with information about the cat(s) preferences for resting locations, and the frequency, volume and characteristics of deposited of urine/faeces. The client should also be asked to indicate in which locations urine/faeces was first found, and how this spread to other locations. A standard method of annotation is to mark the frequency of urine deposition with using a number of "X"s, and a number to indicate whether the location was one of the first, or later, places that was soiled. (see example)

The pattern of urine and faecal deposits can point to the source of the problem. For example, if the first deposits were found close to external doors and windows, this suggests that the perceived threat is from outside the home, whilst initial deposits furniture and internal doorways and passages would suggest that the problem originates in the relationship between resident cats in a multi-cat household.

Once all of this information has been collected, it is then possible to make judgments about the nature of the problem, whether it is a matter of indoor marking or elimination and what the motivation may be.

Differentiating Between Elimination and Marking

Once full information has been collected about the location and characteristics of each urine or faecal deposit, it is possible to differentiate between its cause.

Positioning of Deposits and Reaction to the Litter Tray

In the case of marking, the areas that the cat uses to deposit urine or faeces will often be of behavioural significance, for example areas that smell of the owner or of the new cat in the household or locations which are associated with potential threat from the outside world. There is often a provoking stimulus for this inappropriate behaviour such as some disruption to the home environment or competition within the local neighbourhood and the location of the marking deposits will reflect this. Urine or faecal marks are placed strategically in order to provide a signal to other cats, which means that they must be placed in locations that are likely to be noticed. The act of spraying itself also involves an element of visual display. It should be remembered that odour marks are not merely of use to the ‘sender’ of the signal, who is trying to maintain distance from other cats. They are also of use to the ‘receiver’, who is equally keen to avoid direct physical conflict. The location of scent marks therefore follows conventions that allow other cats to find and investigate them easily. Such places might include on door frames, or on doors, or on pieces of furniture that face doors or windows.

Inappropriate indoor elimination, on the other hand, will usually take place in quiet secluded locations which reflect the sort of places which cats would naturally choose to use as latrines. It is also likely that elimination sites will have certain common characteristics in terms of the substrate that is used and cats will often develop preferences for the inappropriate substrate, such as carpet or linen, and return to similar surfaces repeatedly. These inappropriate substrates may be similar to those the cat was forced to use as a kitten, through an inadequate provision of proper latrines in the rearing environment.

One useful difference between indoor ‘markers’ and ‘toileters’ is their reaction to the indoor latrine facilities, with ‘markers’ often continuing to use the litter tray and ‘toileters’ actively avoiding the facilities provided. Indeed, in cases of a lack of, or a breakdown of house-training, signs of aversion to the litter tray may be the first thing that the owner notices.

Cats with lower urinary tract disease will often use several different sites in the house during the same period, breaking the usual pattern of the cat using only one or two latrines. This is because pain associated with micturition in each of the latrine sites discourages repeated use of the same locations. The cat associates eliminating in that place with pain or dysuria and chooses somewhere else next time. Amounts of urine found at each site may be smaller then normal and have a strong odour or contain blood. This pattern of urination is often cyclical, with cats eliminating normally for a few weeks and then suffering another bout of generalised housesoiling. This fits with the cyclical nature of the severity of lower urinary tract disease, which may wax and wane.

Frequency of Deposits

If a cat is depositing urine and faeces, as part of the normal function of elimination, the frequency will reflect this and deposits will be limited in their number. However, when cats are using the deposits as a form of marking there is no limit on the frequency of deposition and it is not unusual for a urine spraying cat to leave in excess of thirty marks within the home in a 24-hour period.

Volume of Deposits

The amount of urine that is deposited can also help to determine the motivation for the behaviour with toileting problems usually involving larger quantities than marking problems. However, this can be confusing since a small amount of urine can be absorbed by carpets and other fabrics and the size of the moist patch on the floor can be misleading! Cats with Feline Lower Urinary Tract Disease will pass many small quantities of urine in several sites, causing confusion with a marking problem. Likewise, cats with chronic diarrhoea. However, the choice of location will still fit with normal defaecation or urination.

Posture of Cat and Orientation of Deposits

The posture of the cat can help in the differentiation process, since indoor urine spraying is usually associated with a characteristic stance. This is related to the function of the marking behaviour since a standing posture allows the cat to deposit urine on a vertical surface at just the correct height for another cat to sniff at it and take in the important information.

However, urine marking does not exclusively occur from a standing posture and it can be performed from a squatting position, which closely resembles the posture adopted during the act of elimination. This fact must be borne in mind when attempting to differentiate between motivations as it is easy to dismiss squatting urination on horizontal surfaces as always being eliminative and yet there are occasions when the cat is actually using that sort of urination as a marking behaviour.

Pattern of Urine and Faeces Deposition (identified using a house plan)

Certain patterns are classic indicators of a specific underlying motivation. For example, if the first urine marking deposits were found close to external doors and windows it is suggestive that the perceived threat was coming from outside the home, whilst initial deposits in the centre of rooms, corridors or staircases, or onto new pieces of furniture would suggest that the disruption of the cat’s security was coming from within the household. As a situation progresses, the pattern becomes more confusing so that it becomes very difficult to identify the originating cause unless the historical development of the pattern of the marking or elimination is known. For example, urine marking may progress from door and window areas to hallways and rooms if a neighbourhood despot begins to invade the resident cat’s home.

| Indoor Marking | Inappropriate Elimination | |

| Characteristic patterns in urine and faeces deposition: |

|

|

| Behaviour and Posture: |

|

|

| Deposit: |

|

|

| Location: |

|

|

Emotional Factors

In situations of both marking and elimination behaviour within the home, it is important to assess the cat’s emotional status and to attempt to identify any triggers for alteration in that status. Perception of threat either from within or outside the home is commonly associated with the onset of marking behaviour but it is also important to remember that cats that are feeling threatened and insecure may be reluctant to use litter facilities that are positioned in vulnerable locations or that pose difficulties for the cat in terms of competition with other feline household members. In general, it is the insecure and timid feline that is more likely to present with problems of marking behaviour and individuals that do not cope well with change in their environment are going to be predisposed to the use of urine deposits that are designed to increase home security. In addition, cats that are living in a hostile social environment, where there is underlying tension between feline housemates, may use marking behaviour in an attempt to increase distance between them and to avoid overt physical confrontation. Therefore, an assessment of the compatibility between cats in the household is an important part of the investigation process. Likewise, the relationship between the cat and the owner should be considered and questions about the owner’s reaction to the discovery of deposits within the home should be included in the consultation. It is perfectly understandable for people to find it unacceptable that their pet is depositing urine or faeces within their home but the use of punitive techniques may be a factor in perpetuating the behaviour and confirming the cat’s perception that the house is no longer a secure core territory.

Owners often misinterpret relationships between cats in multi-cat households because they are unaware of the significance of certain behaviours. For example, cats will often be described as ‘getting on well’ because they eat and rest in proximity to one another on the owner’s bed or couch. Unfortunately, this apparent tolerance may exist only because the cats are forced to be close to each other when they are feeding or resting. They have no other choice because there are no other feeding stations or equivalent resting places. The cats may be very wary and hesitant whilst feeding and the owner will report that there are frequent bouts of hissing or spitting around the food bowl. Likewise, as one cat leaves a resting place or feeding area, it may be pursued or attacked and cats may attempt long distance intimidation, such as staring eye contact, to frighten each other away from resting places or latrines. Some cats will try to pull food out of a dish with their paws so that they can take it to eat in private. The same desire for privacy will drive them to make a toilet of their own somewhere in the house.

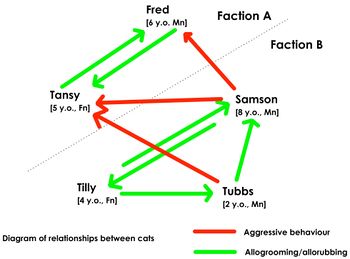

It is important to make a formal assessment of the relationships between cats in the household. A diagram should be constructed to illustrate the relationships. The social function of cats that have died or been re-homed may be important so it may be necessary to draw more than one diagram to illustrate the changing relationships as cats have departed or been added to the group.

Positive affiliative reactions that should be noted include allorubbing and allogrooming, tail up and trilled greeting between cats. Aggressive behaviours include active threats such as chasing, hissing or spitting and physical attacks, as well as more passive or distant threats such as staring eye contact, threatening body or facial posture, or spraying in front of other cats. These classes of behaviour and their direction should be noted on a diagram of interactions, as illustrated in the figure. This may enable certain factions to be identified within the household. Combined with the information already obtained about where cats spend most of their time in the household, this makes the allocation of resources easier during treatment. It may also help to identify feline despots. Making an assessment of this kind is important even when looking at a multi-cat household with what appears to be reactionary spraying due to conflict with outside cats. If resources in the home are sparse, then certain cats may perceive there to be a local overpopulation problem which is made worse by competition with outside cats. Sorting out internal conflict is likely to improve the cats’ general welfare as well as help to resolve elimination and marking problems.

Identifying the Culprit

It is very important to properly identify the culprit(s) for the indoor housesoiling. Clients frequently blame a particular animal, usually because they have seen it eliminating in the house. However, other cats may also be involved. Fluorescein dye or sweet corn may be administered, starting with the cats that are least likely to be involved in the problem.

If faecal soiling is involved, then a small amount of indigestible material is added to each cat’s food for several days and the faeces are inspected. Crushed sweet corn works very well because it is easy to identify in the faeces and does not upset digestion.

Using Fluorescein to Identify Urine Marking or Soiling Cats

It is possible to use fluorescein dye to identify the urine of each cat in the household so that the identity of the soiling cat can be confirmed. Recent research has shown that the fluorescence of urine spots from fluorescein treated cats may vary with urine pH. The fluorescence of fluorescein varies with pH, such that it only strongly emits light under UV illumination when it is in a neutral or alkaline solution. In acidic solution it may hardly glow green at all. Spots should therefore be sprayed with a buffer solution of sodium bicarbonate (baking soda), which will produce a pH of around 8, before testing with a UV lamp.

- Fluorescein is available as sterile paper strips, for ophthalmic examination. These contain approximately 1 mg of fluorescein per tip, but this should be checked with the manufacturer.

- The tips should be torn off and rolled to fit into gelatine capsules, giving approximately 5 per capsule (5mg).

- This dose is given once daily for 3-4 days.

- Urine sites are checked daily.

- Lightly spray each site with a solution of sodium bicarbonate (baking powder), mixed in water (1 tablespoonful in 125ml water).

- A UV lamp is then used to check the site for fluorescence.

- It is vital to start by testing the least probable culprits first, working up to the most probable. Otherwise fluorescence marks left by one cat will obscure those of another. If it is certain that the culprit is a resident cat then the culprit may be identified by a process of elimination, which minimises the risk of leaving lots of fluorescent stains for the client to

clean up.

- A 5-day washout is left between testing of each cat, to make sure that each individual has excreted all of the dye before testing the next.

- Although fluorescein is water-soluble and can usually be removed with normal cleaning, this testing method may leave stains on fabric, carpets or wall paper and owners must be warned of this.

Cooperation Between Cat Owners

Cat ownership is increasing, which means that local feline population density may be very high, and rising. The problems of house soiling and indoor marking that affect one cat owner may also be affecting others. Indoor and outdoor environmental modification can have a much more dramatic effect on the welfare and behaviour of cats, if all cat owners in a neighbourhood make the same changes. Veterinary practices should encourage neighbours to work together to solve problems that arise form overpopulation and inter-cat conflict. Distribution of advice leaflets and running educational evening can help, and will gain good publicity for the practice. It can be beneficial for clients to be educated in feline behaviour, social structure and resource requirements.

References

Also see:

| This article is still under construction. |