Difference between revisions of "Nick's Sandpit"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

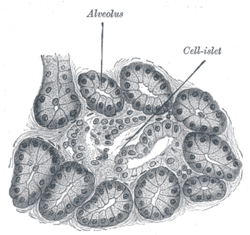

| − | + | [[File:Gray1105.png|thumb|250px|right|Illustration of a dog's pancreas. Cell-islet in the illustration refers to a pancreatic cell in the [[Islets of Langerhans]], which contain insulin-producing [[beta cell]]s and other endocrine related cells. Permanent damage to these beta cells results in [[Diabetes mellitus type 1|Type 1]], or insulin-dependent diabetes, for which [[exogenous]] insulin replacement therapy is the only answer.]] | |

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

| − | | | ||

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | < | + | '''Diabetes mellitus''' is a disease in which the [[beta cell]]s of the [[endocrine pancreas]] either stop producing insulin or can no longer produce it in enough quantity for the body's needs. The condition is commonly divided into two types, depending on the origin of the condition: [[Type 1 diabetes]], sometimes called "juvenile diabetes", is caused by destruction of the beta cells of the [[pancreas]]. The condition is also referred to as insulin-dependent diabetes, meaning [[exogenous]] insulin injections must replace the insulin the pancreas is no longer capable of producing for the body's needs. Dogs have insulin-dependent, or Type 1, diabetes; research finds no Type 2 diabetes in dogs.<ref>{{Cite web|url =http://www.staff.ncl.ac.uk/philip.home/who_dmc.htm |title= Definition, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus | author = Alberti, KGMM|coauthors= Aschner, P., et. al|year = 1999|publisher =World Health Organization|accessdate = 17 March 2010}}</ref><ref name="Type 1">{{Cite web|url =http://www.vetsulin.com/dog-owner/faq.aspx#11|title = Difference Between Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes|author = Vetsulin |publisher = Intervet|accessdate= 17 March 2010}}</ref><ref name=Old>{{cite web|url=http://www.springerlink.com/content/ju2447493k92jlk5/fulltext.pdf|title=Canine diabetes mellitus: can old dogs teach us new tricks?|author=Catchpole, B., Ristic, J.M., Fleeman, L.M., Davison, L.J.|year=2005|publisher=Diabetologica|accessdate=25 January 2011}} ([[PDF]])</ref> Because of this, there is no possibility the permanently damaged pancreatic beta cells could re-activate to engender a remission as may be possible with some [[Diabetes in cats|feline diabetes]] cases, where the primary type of diabetes is Type 2.<ref name="Type 1"/><ref name = "Greco">{{Cite web|url= http://www.bd.com/us/diabetes/page.aspx?cat=7001&id=7404|author=Greco, Deborah|title= Ask Dr. Greco|publisher = BD Diabetes|accessdate = 17 March 2010}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.uq.edu.au/vetschool/centrecah/index.html?page=43391&pid=0 |title= Understanding Feline Diabetes Mellitus |author= Rand, Jacqueline|author2=Marshall, Rhett|year =2005|publisher= Centre for Companion Animal Health, School of Veterinary Science, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia|accessdate= 17 March 2010}}</ref> There is another less common form of diabetes, [[diabetes insipidus]], which is a condition of insufficient [[vasopressin|antidiuretic hormone]] or resistance to it.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/40507.htm&word=diabetes%2cinsipidus|title=Diabetes Insipidus|publisher=Merck Veterinary Manual|accessdate=1 June 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.provet.co.uk/health/diseases/diabetesinsipidus.htm|title=Diabetes Insipidus|publisher=ProVet UK|accessdate=2 November 2011}}</ref> |

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | </ | + | This most common form of diabetes strikes 1 in 500 [[dog]]s.<ref>{{Cite web|url= http://www.petdiabetesmonth.com/dog_how.asp |title =How Common Is It (Diabetes)?|author = Pet Diabetes Month|publisher= Intervet|accessdate=16 April 2010}} |

| − | | | + | </ref> The condition is treatable and need not shorten the animal's life span or interfere with quality of life.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.petdiabetesmonth.com/dog_faq.asp#13 | title= Lifespan of Diabetic Dogs|author = Pet Diabetes Month|publisher= Intervet |accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref> If left untreated, the condition can lead to cataracts, increasing weakness in the legs (neuropathy), [[malnutrition]], [[diabetic ketoacidosis|ketoacidosis]], [[dehydration]], and death.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/100604.htm|title=Diabetic neuropathy|publisher=Merck Veterinary Manual|accessdate=8 April 2011}}</ref> Diabetes mainly affects middle-age and older dogs, but there are juvenile cases.<ref name=Old/><ref name=Pathogenesis>{{Cite web|url= http://www.vetsulin.com/PDF/20585.pdf |title = Pathogenesis-page 3|author = Vetsulin|publisher= Intervet|accessdate=17 March 2010}} ([[PDF]])</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url= http://www.peteducation.com/article.cfm?c=2+1579&aid=860 |title =Juvenile Onset Diabetes Mellitus (Sugar Diabetes) in Dogs & Puppies |author = Foster, Race|publisher =Drs. Foster & Smith-Pet Education|accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref> The typical [[dog|canine]] diabetes patient is middle-age, female, and [[overweight]] at diagnosis.<ref name = "Bruyette">{{Cite web |url=http://www.vin.com/VINDBPub/SearchPB/Proceedings/PR05000/PR00105.htm |title = Diabetes Mellitus: Treatment Options|author = Bruyette, David|year = 2001|publisher =World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA)|accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref> |

| − | }} | ||

| − | <br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br> | + | The number of dogs diagnosed with diabetes mellitus has increased three-fold in thirty years. In survival rates from almost the same time, only 50% survived the first 60 days after diagnosis and went on to be successfully treated at home. Currently, diabetic dogs receiving treatment have the same expected lifespan as non-diabetic dogs of the same age and gender.<ref name = "Rand">{{Cite web|url =http://www.uq.edu.au/vetschool/centrecah/index.html?page=43392&pid=41544 |title =Beyond Insulin Therapy: Achieving Optimal Control in Diabetic Dogs |author =Fleeman, Linda|author2=Rand, Jacqueline|year = 2005|publisher= Centre for Companion Animal Health, School of Veterinary Science, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia|accessdate = 17 March 2010}}</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | ==Classification and causes== | ||

| + | |||

| + | At present, there is no international standard classification of diabetes in dogs.<ref name=Old/> Commonly used terms are: | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Insulin deficiency diabetes or primary diabetes, which refers to the destruction of the beta cells of the pancreas and their inability to produce insulin.<ref name=Old/><ref name=AboutDM>{{cite web |url=http://www.vetsulin.com/vet/AboutDiabetes_Etiology.aspx |title=Canine Etiology|publisher=Intervet|accessdate=20 June 2011}}</ref> | ||

| + | *[[Insulin resistance]] diabetes or secondary diabetes, which describes the resistance to insulin caused by other medical conditions or by hormonal drugs.<ref name=Old/><ref name=AboutDM/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | While the occurrence of beta cell destruction is known, all of the processes behind it are not. Canine primary diabetes mirrors Type 1 human diabetes in the inability to produce insulin and the need for exogenous replacement of it, but the target of canine diabetes autoantibodies has yet to be identified.<ref name=Genes>{{cite web |url=http://jhered.oxfordjournals.org/content/98/5/518.long |title=Analysis of Candidate Susceptibility Genes in Canine Diabetes |author=Short, Andrea D., Catchpole, B., Kennedy, Lorna J., Barnes, Annette, Fretwell, Neale, Jones, Chris, Thomson, Wendy, Ollier, William E.R.|publisher=Journal of Heredity|date=4 July 2007|accessdate=20 June 2011}}</ref> Breed and treatment studies have been able to provide some evidence of a genetic connection.<ref name=Study1>{{cite journal|doi=10.1111/j.1939-1676.2007.tb01940.x|title=Diabetes mellitus in a population of 180,000 insured dogs: incidence, survival, and breed distribution|author=Fall, T., Hamlin, H.H., Hedhammar, Å., Kämpe, O., Egenvall, A.|publisher=Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine|date=November–December 2007}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|pmid=17617163|title=Canine diabetes mellitus: from phenotype to genotype|author=Catchpole B, Kennedy LJ, Davison LJ, Ollier WE.|publisher=The Journal of Small Animal Practice|date=January 2008|doi=10.1111/j.1748-5827.2007.00398.x|volume=49|issue=1|journal=J Small Anim Pract|pages=4–10}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|pmid=20196832|title=CTLA4 promoter polymorphisms are associated with canine diabetes mellitus|author=Short, A.D., Saleh, N.M., Catchpole, B., Kennedy, L.J., Barnes, A., Jones, C.A., Fretwell, N., Ollier. W.E.|publisher=Tissue Antigens|date=March 2010|doi=10.1111/j.1399-0039.2009.01434.x|volume=75|issue=3|journal=Tissue Antigens|pages=242–52}}</ref><ref name=Study2>{{cite web|url=http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2000.216.1414?prevSearch=allfield%253A%2528diabetes%2Bmellitus%2529&searchHistoryKey=|title=Breed distribution of dogs with diabetes mellitus admitted to a tertiary care facility|author=Hess, Rebecka S., Kass, Philip H., Ward, Cynthia R.|publisher=Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association|date=1 May 2000|accessdate=20 June 2011}}</ref> Studies have furnished evidence that canine diabetes has a seasonal connection not unlike its human Type 1 diabetes counterpart, and a "lifestyle" factor, with pancreatitis being a clear cause.<ref name=ArmstrongWestern2011/><ref name=Nature>{{Cite web |url=http://jn.nutrition.org/cgi/content/full/134/8/2072S |title=Canine and Feline Diabetes Mellitus: Nature or Nurture?|year=2004 |author=Rand, Jacqueline|coauthors= Fleeman, Linda, et al.|publisher=Centre for Companion Animal Health, School of Veterinary Science, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia|accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref> This evidence suggests that the disease in dogs has some environmental and dietary factors involved.<ref name=Old/><ref name=VetRecord>{{cite journal|pmid=15828742|title=Study of 253 dogs in the United Kingdom with diabetes mellitus|author=Davison, L.J., Herrtage, M.E., Catchpole, B.|publisher=The Veterinary Record|date=9 April 2005|volume=156|issue=15|journal=Vet. Rec.|pages=467–71}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|pmid=3652619|title=Canine diabetes mellitus has a seasonal incidence: implications relevant to human diabetes|author=Atkins, C.E., MacDonald, M.J.|publisher=Diabetes Research (Edinburgh, Scotland)|date=June 1987|volume=5|issue=2|journal=Diabetes Res.|pages=83–7}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Secondary diabetes may be caused by use of steroid medications, the hormones of [[Estrus#Estrus|estrus]], [[List of dog diseases#Endocrine diseases|acromegaly]], ([[Neutering#Females .28spaying.29|spaying]] can resolve the diabetes), pregnancy, or other medical conditions such as [[Cushing's syndrome|Cushing's disease]].<ref name=AboutDM/><ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0630.x|title=Diabetes Mellitus in Elkhounds Is Associated with Diestrus and Pregnancy |author=Fall, T., Hedhammar, Å., Wallberg, Fall, A.N., Ahlgren, K.M., Hamlin, H.H., Lindblad-Toh, K., Andersson, G., Kämpe, O. |publisher=Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine|date=November–December 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1111/j.1939-1676.2008.0199.x|title=Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in 13 Dogs|author=Fall, T., Johansson Kreuger, S., Juberget, Å., Bergström, A., Hedhammar, Å.|publisher=Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine|date=November–December 2008}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23164637|title=Diabetes mellitus remission after resolution of inflammatory and progesterone-related conditions in bitches|author=Poppl. A. G., Mottin, T. S., Gonzalez, F. H. D.|publisher=Research in Veterinary Science|date=June 2013|accessdate=14 December 2013}}</ref> In such cases, it may be possible to treat the primary medical problem and revert the animal to non-diabetic status.<ref name=Moncrieff/><ref name=Chronolab>{{cite web|url=http://www.chronolab.com/point-of-care/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=28&Itemid=45|title=Hormones Which Raise or Lower Blood Glucose |publisher=Chronolab|accessdate=1 December 2010}}</ref><ref name=Feeney>{{cite journal |url=http://www.veterinaryirelandjournal.com/Links/PDFs/CE-Small/CESA_September_07.pdf|title=How Do You Solve a Problem Like Diabetes? |author=Feeney, Clara|work=Irish Veterinary Journal|date=September 2007|volume=60|issue=9|pages=548–552}}</ref> Returning to non-diabetic status depends on the amount of damage the pancreatic insulin-producing beta cells have sustained.<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Providing Care for Veterinary Diabetic Patients-Canine Diabetes|author=Davidson, Gigi|year=2000|work=International Journal of Pharmaceutical Compounding}}</ref><ref name = "Herrtage" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | It happens rarely, but it is possible for a [[Canine pancreatitis|pancreatitis]] attack to activate the endocrine portion of the organ back into being capable of producing insulin once again in dogs.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.vetinfo.com/ddiabt.html |title=Vet Info 4 Dogs--"Diabetes with rebound hyperglycemia" Question|author=Richards, Mike|publisher=Richards, Mike|accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref> It is possible for acute pancreatitis to cause a temporary, or transient diabetes, most likely due to damage to the endocrine portion's beta cells.<ref name=ArmstrongWestern2011/> Insulin resistance that can follow a pancreatitis attack may last for some time thereafter.<ref name=Hyperglycemia>{{Cite journal |title=Hyperglycemia in Diabetic Dogs and Cats|author=Schermerhorn, Thomas|work=Compendium Standards of Care|pages=7–16}}</ref> Pancreatitis can damage the endocrine pancreas to the point where the diabetes is permanent.<ref name=ArmstrongWestern2011>{{cite journal|title=Canine Pancreatitis: Diagnosis and Management|author=Armstrong, P. Jane|year=2011|work=Western Veterinary Conference}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Genetic susceptibility of certain breeds=== | ||

| + | This list of risk factors for canine diabetes is taken from the genetic breed study that was published in 2007. Their "neutral risk" category should be interpreted as insufficient evidence that the dog breed genetically shows a high, moderate, or a low risk for the disease. All risk information is based only on discovered genetic factors.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://jhered.oxfordjournals.org/content/98/5/518/T3.expansion.html|title=Analysis of Candidate Susceptibility Genes in Canine Diabetes-Breed List|author=Short, Andrea D., Catchpole, B., Kennedy, Lorna J., Barnes, Annette, Fretwell, Neale, Jones, Chris, Thomson, Wendy, Ollier, William E.R.|publisher=Journal of Heredity|date=4 July 2007|accessdate=20 June 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23265864|title=Genetics of canine diabetes mellitus: are the diabetes susceptibility genes identified in humans involved in breed susceptibility to diabetes mellitus in dogs?|publisher=Veterinary Journal|date=21 December 2012|author=Short, Andrea D., Catchpole, B., Holder, AL, Ollier, William E.R,, Kennedy, LJ|accessdate=14 December 2013}}</ref> | ||

| + | {{col-begin}} | ||

| + | {{col-break}} | ||

| + | '''High risk''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | *[[Cairn Terrier]] | ||

| + | *[[Samoyed (dog)|Samoyed]] | ||

| + | {{col-break}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Moderate risk''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | *[[Bichon Frise]] | ||

| + | *[[Border Collie]] | ||

| + | *[[Border Terrier]] | ||

| + | *[[Collie]] | ||

| + | *[[Dachshund]] | ||

| + | *[[English Setter]] | ||

| + | *[[Poodle]] | ||

| + | *[[Schnauzer]] | ||

| + | *[[Yorkshire Terrier]] | ||

| + | {{col-break}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Neutral risk''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | *[[Cavalier King Charles Spaniel]] | ||

| + | *[[Cocker Spaniel]] | ||

| + | *[[Doberman Pinscher|Doberman]] | ||

| + | *[[Jack Russell Terrier]] | ||

| + | *[[Labrador Retriever]] | ||

| + | *[[Mixed-breed dog|Mixed Breed]] | ||

| + | *[[Rottweiler]] | ||

| + | *[[West Highland Terrier]] | ||

| + | {{col-break}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Low risk''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | *[[Boxer (dog)|Boxer]] | ||

| + | *[[English Springer Spaniel]] | ||

| + | *[[German Shepherd]] | ||

| + | *[[Golden Retriever]] | ||

| + | *[[Staffordshire Bull Terrier]] | ||

| + | *[[Weimaraner]] | ||

| + | *[[Welsh Springer Spaniel]] | ||

| + | {{col-end}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Gene therapy=== | ||

| + | In February 2013 scientists successfully cured [[type 1 diabetes]] in [[dog]]s using a pioneering [[gene therapy]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/content/62/5/1718.long|title=Treatment of Diabetes and Long-Term Survival After Insulin and Glucokinase Gene Therapy|publisher=American Diabetes Association|date=May 2013|editor-last=Callejas|editor-first=David|editor2-last=Mann|editor2-first=Christopher J.|editor3-last=Ayuso|editor3-first=Lage|editor3-first=Ricardo|accessdate=14 December 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22405830|title=Novel diabetes mellitus treatment: mature canine insulin production by canine striated muscle through gene therapy|date=July 2012|publisher=Domestic Animal Endocrinology|author=Niessen SJ, Fernandez-Fuente, M., Mahmoud, A., Campbell, S. C., Aldibbiat, A., Huggins, C., Brown, A. E., Holder, A., Piercy, R. J., Catchpole, B., Shaw, J. A., Church, David B.|accessdate=14 December 2012}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Pathogenesis== | ||

| + | The body uses [[Glucose#Function|glucose]] for energy. Without insulin, glucose is unable to enter the cells where it will be used for this and other [[Anabolism|anabolic]] ("building up") purposes, such as the synthesis of glycogen, proteins, and fatty acids.<ref name=Pathogenesis/><ref>{{cite book|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK30/#A60|title=Endocrinology: An Integrated Approach|editor-last=Nussey|editor-first=S.|editor2-last=Whitehead|editor2-first=S.|year=2001|publisher=BIOS Scientific Publications|accessdate=22 June 2011}}</ref> Insulin is also an active preventor of the breakdown or [[catabolism]] of glycogen and fat.<ref name=Amy/> The absence of sufficient insulin causes this breaking-down process to be accelerated; it is the mechanism behind metabolizing fat instead of glucose and the appearance of ketones.<ref name=Pathogenesis/><ref name=Dean>{{cite book|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1671/|title=The Genetic Landscape of Diabetes|editor-last=Dean|editor-first=L.|editor2-last=McEntyre|editor2-first=J.|year=2004|publisher=National Center for Biotechnology Information (US)|accessdate=22 June 2011}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since the glucose that normally enters the cells is unable to do so without insulin, it begins to build up in the blood where it can be seen as hyperglycemia or high blood glucose levels. The [[Nephron#Renal tubule|tubules]]<!-- [[Nephron]] --> of the kidneys are normally able to re-absorb glucose, but they are unable to handle and process the amount of glucose they are being presented with. At this point, which is called the renal threshold, the excess glucose spills into the urine ([[glycosuria]]), where it can be seen in urine glucose testing.<ref name="Diabetes"/><ref name=Taylor>{{cite web |url=http://www.dcavm.org/06technov.html |publisher=District of Columbia Academy of Veterinary Medicine |year=2006 |author=Taylor, Judith A.|title=Harvesting the Gold-Urinalysis|accessdate=22 June 2011}}</ref> It is the [[polyuria]], or over-frequent urination, which causes [[polydipsia]], or excessive water consumption, through an [[Osmotic diuresis|osmotic process]].<ref name=Pathogenesis/> Even though there is an overabundance of glucose, the lack of insulin does not allow it to enter the cells. As a result, they are not able to receive nourishment from their normal glucose source. The body begins using fat for this purpose, causing weight loss; the process is similar to that of [[starvation]].<ref name=Pathogenesis/><ref name=Dean/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Symptoms== | ||

| + | [[File:Dog with complete cataracts.jpg|right|thumb|200px|This dog has complete cataracts; the clouding of its eyes can be easily seen. Depending on the condition of the eyes and the overall health of the dog, it is often possible to have them surgically removed, restoring sight.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.acvo.org/new/public/common_diseases/cataracts.shtml |title=Cataracts|publisher=American College of Veterinary Ophthalmologists|accessdate=17 August 2010}}</ref>]] | ||

| + | Generally there is a gradual onset of the disease over a few weeks, and it may escape unnoticed for a while. The main [[symptom]]s are:<ref name ="AAHA"/><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.petdiabetesmonth.com/dog_diagnosis.asp |title =Diagnosis and Detection|author=Pet Diabetes Month|publisher= Intervet|accessdate= 17 March 2010}}</ref><ref name=Meisler/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | * excessive water consumption– [[polydipsia]] | ||

| + | * frequent and/or excessive urination–[[polyuria]]–possible house "accidents" | ||

| + | * greater than average appetite–[[polyphagia]]–with either weight loss or maintenance of current weight | ||

| + | * cloudy eyes–[[Cataracts]]<ref name=Eye>{{cite journal|title=Ocular Manifestations of Endocrine Disease |author=Plummer, Caryn E., Specht, Andrew, Gelatt, Kirk N.|work=Compendium|date= December 2007|pmid=18225637 |pages=733–743 |volume=29|issue=12}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.webcitation.org/5ydEuh9M6|title=Ophthalmology Clinical Trial: Medical Treatment for Cataracts in Diabetic Dogs|publisher=Iowa State University School of Veterinary Medicine|accessdate=16 May 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.southpaws.com/wp-content/newsletters/fall-2008-newsletter.pdf|title=Diabetes and the Eye |author=Bromberg, Nancy M.|year=2008|publisher=Southpaws|accessdate=16 May 2011}}([[PDF]])</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | It is possible that the illness may not be noticed until the dog has symptoms of [[ketosis]] or [[Diabetes in dogs#Ketones .E2.80.93 ketoacidosis|ketoacidosis]].<!-- [[Diabetes in dogs]]--> When newly diagnosed, about 40% of dogs have elevated ketone levels; some are in diabetic ketoacidosis when first treated for diabetes.<ref name=Old/><ref name="Rand"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Management== | ||

| + | Early diagnosis and interventive treatment can mean reduced incidence of complications such as [[cataracts]] and [[neuropathy]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://replay.web.archive.org/20090131063920/http://www.southpaws.com/news/99-2-neuropathy.htm |title=Peripheral Neuropathy|author=Daydrell-Hart, Betsy|year=1999|publisher=Southpaws|accessdate=16 May 2011}}</ref> Since dogs are insulin dependent, oral drugs are not effective for them.<ref name = "Greco" /><ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.veterinarypartner.com/Content.plx?P=A&S=0&C=0&A=627| title =Insulin Alternatives|author= Brooks, Wendy C.|publisher= Veterinary Partner|accessdate= 17 March 2010}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.bd.com/us/diabetes/page.aspx?cat=7001&id=7389|title=Diet for Diabetic Dogs, and Exercise Tips|author=BD Diabetes|publisher= BD Diabetes|accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref> They must be placed on insulin replacement therapy.<ref name= "AAHA"/> Approved [[Anti-diabetic drug|oral diabetes drugs]] can be helpful to sufferers of [[Diabetes mellitus type 2|Type 2 diabetes]] because they work in one of three ways: by inducing the pancreas to produce more insulin, by allowing the body to more effectively use the insulin it produces, or by slowing the [[Glucose#Sources and absorption|glucose absorption]] rate from the [[GI tract]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.marvistavet.com/html/body_insulin_alternatives.html|title=Insulin Alternatives|publisher=MarVista Vet |accessdate=19 April 2011}}</ref> Unapproved [[Quackery#Quackery in contemporary culture|so-called "natural" remedies]] make similar claims for their products.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/edu/pubs/consumer/health/hea07.shtm |title='Miracle' Health Claims: Add a Dose of Skepticism|publisher=US Federal Trade Commission|accessdate=11 June 2010}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=http://petshealth.com/library/nutriceut.html |title=Nutriceutical, Alternative and Complementary Therapies|publisher=Ohio State University |accessdate=11 June 2010 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20040101015746/http://petshealth.com/library/nutriceut.html |archivedate = 1 January 2004}}</ref> All of this is based on the premise of having an [[endocrine pancreas]] with beta cells capable of producing insulin. Those with [[Diabetes mellitus type 1|Type 1]], or insulin-dependent diabetes, have beta cells which are permanently damaged, thus unable to produce insulin.<ref name="Type 1"/> This is the reason nothing other than [[Insulin therapy|insulin replacement therapy]] can be considered real and effective treatment. Canine diabetes mean insulin dependency; insulin therapy must be continued for life.<ref name="Greco"/><ref>{{Cite web |url=http://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/begin/cells/badcom/index.html |title=When the Target Ignores the Signal |publisher=University of Utah Genetic Learning Center|accessdate=11 June 2010}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The goal is to regulate the pet's blood glucose using insulin and some probable diet and daily routine changes.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.k9diabetes.com/regulated.html |title=What Is Regulation?|author= k9diabetes.com |publisher=k9diabetes.com |accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref> The process may take a few weeks or many months. It is basically the same as in Type 1 diabetic humans. The aim is to keep the blood glucose values in an acceptable range. The commonly recommended dosing method is by "starting low and going slow" as indicated for people with diabetes.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.ianblumer.com/insulin_choice.htm |title=Dr. Ian Blumer's Practical Guide to Diabetes|author=Blumer, Ian|publisher=Blumer, Ian|accessdate=17 March 2010 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20080130114528/http://www.ianblumer.com/insulin_choice.htm |archivedate = 30 January 2008}}<br>An MD who advises his human patients to Start Low and Go Slow.</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.ianblumer.com/insulin+initiation.htm |title=Insulin Initiation|author=Blumer, Ian|publisher=Blumer, Ian |accessdate=17 March 2010 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20080606044135/http://www.ianblumer.com/insulin+initiation.htm |archivedate = 6 June 2008}}<br>Dr. Blumer's Letter to Newly-Diagnosed Human Diabetics in His Practice</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.pediatriconcall.com/forpatients/CommonChild/Endocrine_problems/insulin.htm |title=Insulin Therapy|author=Pediatric OnCall|publisher=Pediatric OnCall|accessdate=17 March 2010 |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20080308011924/http://www.pediatriconcall.com/forpatients/CommonChild/Endocrine_problems/insulin.htm|archivedate=8 March 2008}}</ref> Typical starting insulin doses are from 0.25 IU/kg (2.2 lb)<ref name = "Nelson"/> to 0.50 IU/kg (2.2 lb)<ref name = "Bruyette" /> of body weight.<ref name="AAHA"/><ref name=GrecoWestern>{{cite journal|title=Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus in Dogs and Cats|year=2010|page=2|author=Greco, Deborah|work=Western Veterinary Conference}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | During the initial process of regulation and periodically thereafter, the effectiveness of the insulin dose at controlling blood glucose needs to be evaluated.<ref name="Vetstream"/> This is done by a series of blood glucose tests called a curve. Blood samples are taken and tested at intervals of one to two hours over a 12- or 24-hour period.<ref name = "AAHA"/><ref name=CurvesUS>{{cite web|url=http://www.vetsulin.com/vet/Monitoring_About.aspx|title=Blood Glucose Curves|publisher=Intervet US|accessdate=22 June 2011}}</ref><ref name=CurvesUK>{{cite web|url=http://www.pet-diabetes.co.uk/blood-glucose-dogs.asp|title= About Blood Glucose Curves|publisher=Intervet UK|accessdate=22 June 2011}}</ref> The results are generally transferred into graph form for easier interpretation. They are compared against the feeding and insulin injection times for judgment.<ref name="Vetstream"/> The curve provides information regarding the action of the insulin in the animal. It is used to determine insulin dose adjustments, determine lowest and highest blood glucose levels, discover insulin duration and, in the case of continued hyperglycemia, whether the cause is insufficient insulin dose or [[Chronic Somogyi rebound|Somogyi rebound]], where blood glucose levels initially reach hypoglycemic levels and are brought to hyperglycemic ones by the body's [[counterregulatory hormone]]s.<ref name=Chronolab/><ref name=Feeney/> Curves also provide evidence of insulin resistance which may be caused by medications other than insulin or by disorders other than diabetes which further testing can help identify.<ref name=CurvesUS/><ref name=CurvesUK/><ref name =Australia>{{Cite web |url=http://www.caninsulin.com/|title=Caninsulin |publisher=Intervet|accessdate=20 May 2010}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other diagnostic tests to determine the level of diabetic control are [[fructosamine]] and glycosylated hemoglobin (GHb) blood tests which can be useful especially if stress may be a factor.<ref name=Monitor>{{cite web |url=http://www.vetsulin.com/vet/Monitoring_Glycated.aspx|title=Monitoring and controlling diabetes mellitus |publisher=Intervet|accessdate=3 October 2011}}</ref> While anxiety or stress may influence the results of blood or urine glucose tests, both of these tests measure glycated proteins, which are not affected by them. Fructosamine testing provides information about blood glucose control for an approximate 2 to 4 week period, while GHb tests measure a 2 to 4 month period. Each of these tests has its own limitations and drawbacks and neither are intended to be replacements for blood glucose testing and curves, but are to be used to supplement the information gained from them.<ref name="AAHA"/><ref name=Monitor/><ref>{{cite web |url=http://web.archive.org/web/20070210032737/http://www.antechdiagnostics.com/clients/antechnews/2000/jan00_01.htm |title=Fructosamine and Glycosylated Hemogloblin|date=January 2000|publisher=Antech|accessdate=3 October 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.vet.uga.edu/VPP/clerk/Bates/index.php|title=Fructosamine Measurement in Diabetic Dogs and Cats|author=Bates, Hunter E., Bain, Perry J., Krimer, Paula M., Latimer, Kenneth S.|year=2003|publisher=University of Georgia School of Veterinary Medicine|accessdate=3 October 2011}}</ref> While HbA1c tests are a common diagnostic for diabetes in humans, there are no standards of measurement for use of the test in animals. This means the information from them may not be reliable.<ref name=GlucoseMarkers>{{cite web|url=https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&q=cache:eOusZZInsYUJ:stud.epsilon.slu.se/813/1/mared_m_100128.pdf+hba1c+dogs&hl=en&gl=us&pid=bl&srcid=ADGEESi6-rBLJZyniP-O5wc93xLIofwipMQ1QVfZZs5g6QhozFEW866JwwkcwtOZNILApK0kbUWrAuAzBUbCtDxpATvF0XWvpzev0oSyItA7PvQe4n2E0xT7h8BpUZdj5q1ARFW6WWs1&sig=AHIEtbQR6ZlBRb0wcQSCaTVgIi3Hc4Cx-g|title=Glucose markers in healthy and diabetic bitches in different stages of the oestral cycle|author=Mared, Malin|publisher=Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet (Upsala, Sweden)|year=2010|accessdate=3 October 2011}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The diabetic pet is considered regulated when its blood glucose levels remain within an acceptable range on a regular basis. Acceptable levels for dogs are between 5 and 10 mmol/L or 90 to 180 mg/dL.<ref name = "Rand" /><ref name="Valley"/> The range is wider for diabetic animals than non-diabetics, because insulin injections cannot replicate the accuracy of a working pancreas.<ref>{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=R98umtVlEVUC&pg=RA1-PA226&lpg=RA1-PA226&dq=replication+of+insulin+secretion+insulin+therapy&source=bl&ots=dIPZ10EQFM&sig=FwYVb9QivRWVyJRnq-OYvA6YpKs&hl=en&ei=BKOtTbHnKcbcgQfPoJGJDA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CB8Q6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=replication%20of%20insulin%20secretion%20insulin%20therapy&f=false|title=Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: integrating science and clinical medicine|editor-last=Marso|editor-first=Stephen P.|editor2-last=Stern|editor2-first=David M.|publisher=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins|year=2003|pages=226|isbn= 978-0-7817-4053-1|accessdate=19 April 2011}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Insulin therapy=== | ||

| + | The general form of this treatment is an intermediate-acting basal insulin with a regimen of food and insulin every 12 hours, with the insulin injection following the meal.<ref name ="AAHA"/><ref name ="Regulating">{{Cite web|url=http://veterinaryteam.dvm360.com/firstline/ArticleStandard/Article/detail/662017|title=Regulating diabetes mellitus in dogs and cats|date=1 March 2010|author=Sereno, Robin|publisher=DVM 360|accessdate=20 May 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=iCm1SJBDZwkC&pg=PA1104&dq=protamine+zinc+insulin&hl=en&ei=IUXRTZXZHc2_gQeBzbHFDA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CDcQ6AEwAjgK#v=onepage&q=protamine%20zinc%20insulin&f=false|title=Polymeric Biomaterials, Revised and Expanded|editor-last=Dumitriu |editor-first=Severian|year=2001|publisher=CRC Press|pages=1104|isbn=0-8247-0569-6|accessdate=16 May 2011}}</ref> The most commonly used intermediate-acting insulins are [[NPH insulin|NPH]], also referred to as isophane,<ref name=NPH>{{cite web|url=http://www.inchem.org/documents/pims/pharm/insulin.htm#SectionTitle:3.3 Physical properties|title=British Pharmacopia definition of Isophane insulin|publisher=InChem|accessdate=31 March 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author=Goeders LA, Esposito LA, Peterson ME |title=Absorption kinetics of regular and isophane (NPH) insulin in the normal dog |publisher=Domestic Animal Endocrinology |date=January 1987|url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0739-7240(87)90037-3|accessdate=21 June 2011}}</ref> or Caninsulin, also known as Vetsulin, a porcine Lente insulin.<ref>[http://www.vetstreamcanis.co.uk/drugs/datasht/v29c1100.htm]</ref><ref>[http://www.vetsulin.com/vet/AboutVet_Overview.aspx ]</ref><ref name=Lente>{{cite web|url=http://www.inchem.org/documents/pims/pharm/insulin.htm#SectionTitle:3.3 Physical properties|title=British Pharmacopia definition of Lente insulin (Insulin Zinc Suspension)|publisher=InChem|accessdate=31 March 2011}}</ref> While the normal diabetes routine is timed feedings with insulin shots following the meals, dogs unwilling to adhere to this pattern can still attain satisfactory regulation.<ref name = "Schall" /> Most dogs do not require [[Basal (medicine)|basal/bolus]] insulin injections; treatment protocol regarding consistency in the diet's calories and composition along with the established feeding and injection times is generally a suitable match for the chosen intermediate-acting insulin.<ref name=Long/><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.vin.com/VINDBPub/SearchPB/Proceedings/PR05000/PR00157.htm |title=What Can Be Done?-Treating the Complicated Diabetic Patient|year=2001|author=Church, David B.|publisher=World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA)|accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | With [[Insulin glargine|Lantus]] and protamine zinc insulin (PZI)<ref name=PZI>{{Cite web |url=http://www.inchem.org/documents/pims/pharm/insulin.htm#SectionTitle:3.3 Physical properties|title=British Pharmacopia definition of Protamine Zinc Insulin|publisher=InChem|accessdate=21 July 2010}}</ref> being unreliable in dogs, they are rarely used to treat canine diabetes.<ref name=Moncrieff/><ref name="AAHA"/><ref name = "Nelson">{{Cite journal|title= Selecting an Insulin for Treating Diabetes Mellitus in Dogs and Cats|journal=Symposium Proceedings|author= Nelson, Richard|year= 2006|publisher=Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine|page= 40}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.uq.edu.au/ccah/index.html?page=43507&pid=0-Comparison |title=Comparison of The Pharmacodynamics and Pharmacokinetics of Subcutaneous Glargine, Protamine Zinc, and Lente Insulin Preparations In Healthy Dogs|author= Stenner, V.J. |coauthors= Fleeman, Linda, Rand, Jacqueline|year=2004|publisher= Centre for Companion Animal Health, School of Veterinary Science, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia|accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref> Bovine insulin has been used as treatment for some dogs, particularly in the UK.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://classic-web.archive.org/web/20080404152612/www.noahcompendium.co.uk/Schering-Plough_Animal_Health/Insuvet/-34412.html|title=Insuvet: Presentation|publisher=National Office of Animal Health UK|accessdate=5 May 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://classic-web.archive.org/web/20080404152617/www.noahcompendium.co.uk/Schering-Plough_Animal_Health/Insuvet/-34413.html|title=Insuvet: Uses|publisher=National Office of Animal Health UK|accessdate=5 May 2011}}</ref> Pfizer Animal Health discontinued of all three types of its veterinary Insuvet bovine insulins in late 2010 and suggested patients be transitioned to Caninsulin.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.viovet.co.uk/support/index.php?_m=knowledgebase&_a=viewarticle&kbarticleid=23|title=Switching from Insuvet to Caninsulin|author=Church, David B., Mooney, Carmel T., et al.,|date=25 November 2010|publisher=VioVet UK|accessdate=14 December 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.vmd.gov.uk/vet/supply.aspx#insulin|title=No Further Supplies of Insuvet Insulins|publisher=Veterinary Medicines Directorate-UK|accessdate=14 December 2010}}</ref> The original owner of the insulin brand, Schering-Plough Animal Health, contracted [[Wockhardt]] UK to produce them.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.wockhardt.com/part_europe.html |title=Schering-Plough Animal Health Contracts Wockhardt UK for Production of Its Insuvet Insulins|publisher=Wockhardt|accessdate=14 December 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.farminguk.com/news/Pfizer-Animal-Health-Adds-Former-Schering-Plough-Products-to-European-Portfolio_8556.html|title=Pfizer Animal Health Adds Former Schering-Plough Products to European Portfolio|date=11 September 2008|publisher=Farming UK|accessdate=14 December 2010}}</ref> Wockhardt UK has produced both bovine and porcine insulins for the human pharmaceutical market for some time.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/document.aspx?documentId=9769|title=Hypurin Bovine Neutral|publisher=Electronic Medicines Compendium UK|accessdate=14 December 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/document.aspx?documentId=9768|title=Hypurin Bovine Lente|publisher=Electronic Medicines Compendium UK|accessdate=14 December 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/document.aspx?documentId=9763|title=Hypurin Bovine Protamine Zinc|publisher=Electronic Medicines Compendium UK|accessdate=14 December 2010}}</ref> | ||

| + | <br clear=right> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Diet=== | ||

| + | Most of the commercially available prescription diabetes foods are high in fiber, in complex carbohydrates, and have proven therapeutic results.<ref name = "AAHA">{{Cite web|url=http://www.aahanet.org/PublicDocuments/AAHADiabetesGuidelines.pdf |year=2010|title= AAHA Diabetes Management Guidelines for Dogs and Cats|author=Rucinsky, Renee, et al.|publisher=American Animal Hospital Association|accessdate=21 May 2010}} ([[PDF]])</ref><ref name = "Schall">{{Cite web |url=http://veterinarycalendar.dvm360.com/avhc/article/articleDetail.jsp?id=610978&sk=&date=&%0A%09%09%09&pageID=8|title= Diabetes Mellitus-CVC Proceedings|author=Schall, William|year= 2009|publisher=DVM 360|accessdate= 17 March 2010}}</ref> Of primary concern is getting or keeping the animal eating, as use of the prescribed amount of insulin is dependent on eating full meals.<ref name = "Schall" /><ref name = "Cook">{{Cite web |url=http://veterinarymedicine.dvm360.com/vetmed/article/articleDetail.jsp?id=456192&sk=&date=&%0A%09%09%09&pageID=5 |title=Latest Management Recommendations for Cats and Dogs with Nonketotic Diabetes Mellitus|author=Cook, Audrey|year= 2007|publisher=DVM 360|accessdate= 17 March 2010}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.vin.com/proceedings/Proceedings.plx?CID=WSAVA2004&PID=8607&Category=1252&O=Generic|title= Food Intake in Therapy|author=Buffington, Tony|year = 2004|publisher=World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA)|accessdate= 17 March 2010}}</ref> When no meal is eaten, there is still a need for a [[Basal (medicine)|basal]] dosage of insulin, which supplies the body's needs without taking food into consideration.<ref name=Amy>{{cite web|url=http://www.thecapsulereport.com/sa18,1-3.htm |title=Insulin is essential for many metabolic processes|author=Grooters, Amy M.,|date=April 1999|publisher=North American Veterinary Conference|accessdate=22 June 2011|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20070630070405/http://www.thecapsulereport.com/sa18,1-3.htm|archivedate=30 June 2007}}</ref><ref name =Australia/> Eating a partial meal means a reduction in insulin dose. Basal and reduced insulin dose information should be part of initial doctor–client diabetes discussions in case of need.<ref name ="AAHA"/><ref name ="Regulating"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | It is possible to regulate diabetes without any diet change.<ref name="AAHA"/><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.vetsulin.com/vet/Monitoring_Nutrition.aspx |title=Nutrition-Dietary Control|author=Vetsulin|publisher= Intervet|accessdate= 17 March 2010}}</ref> If the animal will not eat a prescribed diet, it is not in the dog's best interest to insist on it; the amount of additional insulin required because a non-prescription diet is being fed is generally between 2–4%.<ref name="Schall"/> Semi moist foods should be avoided as they tend to contain a lot of sugars.<ref name=Moncrieff>{{cite journal|title=Canine & Feline Diabetes Mellitus I|author=Scott-Moncrieff, Catherine|year=2009|work=Western Veterinary Conference}}</ref><ref name ="AAHA"/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.peteducation.com/article.cfm?cls=2&cat=1661&articleid=3328 |title=Dry, Semi-Moist, or Canned-What Type of Food is Best for Your Pet?|publisher=Drs. Foster & Smith-Pet Education|accessdate=29 January 2011}}</ref> Since dogs with diabetes are prone to pancreatitis and [[hyperlipidemia]], feeding a low-fat food may help limit or avoid these complications.<ref name = "Rand"/><ref name="Herrtage"/> A non-prescription food with a "fixed formula" would be suitable because of the consistency of its preparation. Fixed formula foods contain precise amounts of their ingredients so batches or lots do not vary much if at all. "Open formula" foods contain the ingredients shown on the label but the amount of them can vary, however they must meet the guaranteed analysis on the package.<ref name=Diet/> These changes may have an effect on the control of diabetes.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nhahonline.com/k9endocrinology.htm |title=Canine Endocrinology|publisher=New Hope Animal Hospital|accessdate=29 January 2011 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20061113214741/http://www.nhahonline.com/k9endocrinology.htm |archivedate = 13 November 2006}}</ref> Prescription foods are fixed formulas, while most non-prescription ones are open formula unless the manufacturer states otherwise.<ref name=Diet>{{cite web|url=http://www.veterinarypartner.com/Content.plx?P=A&S=0&C=0&A=3060|title=Diet for the diabetic dog|author=Brooks, Wendy C.|publisher=Veterinary Partner|accessdate=29 January 2011}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Glucometers and urine test strips=== | ||

| + | The use of an inexpensive [[glucometer]] and blood glucose testing at home can help avoid dangerous insulin overdoses and can provide a better picture of how well the condition is managed.<ref name=CurvesUK/><ref name= "Regulating"/> Dr. Sara Ford gave a presentation about the need for home blood glucose testing in diabetic pets at the 2010 American Veterinary Medical Association Convention. She believes a diabetic pet needs to be checked at least twice a day, saying, "If you're a human diabetic you monitor your blood sugar between 4-6 times a day. I believe that state-of-the-art care in veterinary medicine in 2010 includes home blood-glucose monitoring."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.avma.org/press/releases/100726_2010convention_diabetes.asp|title=At-home monitoring critical for managing diabetes in pets|date=26 July 2010|publisher=American Veterinary Medical Association|accessdate=5 November 2010|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/5ylSRsgiv|archivedate=16 May 2011}}</ref> | ||

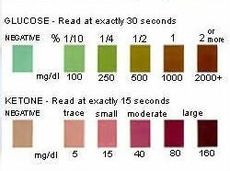

| + | [[File:Ketodiastix.jpg|230px|thumb|'''Ketodiastix''' color chart for interpreting test results. This test measures '''both ketones and glucose''' in urine.]] | ||

| + | A 2003 study of canine diabetes caregivers who were new to testing blood glucose at home found 85% of them were able to both succeed at testing and to continue it on a long-term basis.<ref name="Reusch">{{Cite web|url=http://www.lloydinc.com/pdfs/Endocrinology/Vol14_issue2_2004.pdf|title=Home monitoring of blood glucose concentration by owners of diabetic dogs-page 9|year=2003|author=Casella, M., Wess, G., Hässig, M., Reusch, C.E.|publisher=Journal of Small Animal Practice|accessdate=28 May 2010}} ([[PDF]])</ref><ref name="Monitoring">{{Cite web|url=http://veterinarycalendar.dvm360.com/avhc/article/articleDetail.jsp?id=569938&sk=&date=&pageID=3|title=Strategies for monitoring diabetes mellitus in dogs|year=2008|author=Schermerhorn, Thomas|publisher=DVM 360|accessdate=28 May 2010}}</ref> Using only one blood glucose reading as the reason for an insulin dose increase is to be avoided; while the results may be higher than desired, further information, such as the lowest blood glucose reading or nadir, should be available to prevent possible hypoglycemia.<ref name="Vetstream">{{Cite web|url=http://www.vetstreamcanis.com/ACI/September/VMD2/fre00736.asp|title=Blood glucose curve interpretation|author=Bruyette, David|publisher=Vetstream canis|accessdate=21 July 2010|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/5z523ghfb|archivedate=30 May 2011}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://veterinarymedicine.dvm360.com/vetmed/Medicine/What-you-want-to-know-about-diabetic-regulation/ArticleStandard/Article/detail/673414|title=Reader Questions:What you want to know about diabetic regulation|author=Cook, Audrey|publisher=DVM 360|date=1 June 2010|accessdate=21 July 2010}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Clinistrip|Urine strips]] are not recommended to be used as the sole factor for insulin adjustments as they are not accurate enough.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.vetsulin.com/PDF/20585.pdf Vetsulin|title=Urine Monitoring (page 15)|author=Vetsulin|publisher=Intervet|accessdate=17 March 2010}} ([[PDF]])</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.caninsulin.com/Dose-adjustment-dogs.asp |title=Caninsulin-Dose Adjustment|author=Caninsulin|publisher=Intervet|accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref> Urine glucose testing strips have a negative result until the [[Glucosuria|renal threshold]]<!--[[Diabetes mellitus]]--> of 10 mmol/L or 180 mg/dL is [[Blood sugar#Measurement techniques|reached or exceeded]] <!-- [[Blood sugar]]-->for a period of time.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.vetsulin.com/vet/Monitoring_Urine.aspx |title=Monitoring urine|author=Vetsulin|publisher=Intervet|accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://ahdc.vet.cornell.edu/clinpath/modules/ua-rout/GLUCSTIX.HTM|title=Urine Glucose|publisher=Cornell University|accessdate=25 August 2010}}</ref> The range of negative reading values is quite wide-covering normal or close to normal blood glucose values with no danger of hypoglycemia ([[Diabetes mellitus#Management|euglycemia]]) to low blood glucose values ([[Diabetic hypoglycemia|hypoglycemia]]) where treatment would be necessary.<ref name="Vetstream"/><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.vetinfo.com/dinsulin.html|title=Vet Info 4 Dogs-Regulating Insulin|author=Richards, Mike|publisher=Richards, Mike|accessdate=16 June 2010}}</ref> Because urine is normally retained in the bladder for a number of hours, the results of urine testing are not an accurate measurement of the levels of glucose in the bloodstream at the time of testing.<ref name=Levitan>{{cite web|url=http://veterinarynews.dvm360.com/dvm/article/articleDetail.jsp?id=5336|title=Blood glucose monitoring|author=Levitan, Diane Monsein|year=2001|publisher=DVM Newsmagazine|accessdate=9 August 2011}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Glucometers made for humans are generally accurate using canine and feline blood except when reading lower ranges of blood glucose (<80 mg/dL), (<4.44 mmol/L). It is at this point where the size difference in human vs animal red blood cells can create inaccurate readings.<ref name = "Schall"/><ref>{{Cite journal|title=Evaluation of Six Portable Blood Glucose Meters in Dogs-page 30|author=Cohen, T. et al.|year=2008|publisher=American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM)|work=ACVIM 2008}}</ref> Glucometers for humans were successfully used with pets long before animal-oriented meters were produced.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.veterinarypartner.com/Content.plx?P=A&C=&A=631&SourceID=|title=Diabetes Mellitus Center|author=Brooks, Wendy C.|publisher=Veterinary Partner|accessdate=29 July 2010}}</ref> A 2009 study directly compared readings from both types of glucometers to those of a chemistry analyzer. Neither glucometer's readings exactly matched those of the analyzer, but the differences of both were not clinically significant when compared to analyzer results.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.235.11.1309?prevSearch=allfield%253A%2528glucometer%2529&searchHistoryKey=|title=Comparison of a human portable blood glucose meter, veterinary portable blood glucose meter, and automated chemistry analyzer for measurement of blood glucose concentrations in dogs|author=Johnson, Beth M., Fry, Michael M., Flatland, Bente, Kirk, Claudia A.|publisher=Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association|date=1 December 2009|accessdate=18 June 2011}}</ref> All glucometer readings need to be compared to same sample laboratory values to determine accuracy.<ref name="Vetstream"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Blood glucose guidelines=== | ||

| + | The numbers on the table below are as shown on a typical home glucometer. Seeing ketone values above trace or small is an indication to contact a vet or local emergency treatment center.<ref name = "Davis" /><ref name = "Endocrine">{{Cite web|url=http://veterinarycalendar.dvm360.com/avhc/article/articleDetail.jsp?id=586470&pageID=1&sk=&date= |title=Endocrine emergencies-CVC Proceedings|year=2008|author=Durkan, Samuel|publisher=DVM 360|accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref> | ||

| + | <center> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" border=2 cellpadding=2 style="border-collapse:collapse" | ||

| + | !style="background:#BCD2EE;"|<center> mmol/L<ref name="Measurement">{{Cite web|url=http://www.abbottdiabetescare.com.au/diabetes-faq-measure-units.php|title=Blood Glucose Measurement Units|publisher=Abbott Diabetes Care, Australia|accessdate=9 June 2010}}</ref></center> | ||

| + | !style="background:#BCD2EE;"|<center> mg/dL<ref name="Measurement"/></center> | ||

| + | !style="background:#BCD2EE;"|<center>Blood Glucose Guidelines</center> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !style="background:mistyrose;"|<center><2.77</center> | ||

| + | !style="background:mistyrose;"|<center><50</center> | ||

| + | !style="background:mistyrose;"|<center> Readings at or below this level are considered [[Diabetic hypoglycemia|hypoglycemic]] when using insulin,<br> even without visible hypoglycemia symptoms.<ref name=Tom>{{Cite journal|title=Management of Insulin Overdose|pages= 1–7|author=Schermerhorn, Thomas|journal=Compendium Standards of Care}}</ref> Immediate treatment is needed.<ref name="Pierce">{{Cite web|url=http://www.ahofp.com/Guide/Candiabe.htm |title=Definition of Hypoglycemic values|author=Pierce County Animal Emergency Clinic|publisher=Animal Hospital of Pierce County|accessdate=17 March 2010 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20080512122940/http://www.ahofp.com/Guide/Candiabe.htm |archivedate = 12 May 2008}}</ref></center> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |style="background:ivory;"|<center> 3.44–6</center> | ||

| + | |style="background:ivory;"|<center> 62–108</center> | ||

| + | |style="background:ivory;"|<center> Normal glucose values range for dogs who do not have diabetes.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/htm/bc/tref7.htm Serum |title=Biochemical References Ranges|author=Merck Veterinary Manual|publisher=Merck|accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref></center> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |style="background:ivory;"|<center>5</center> | ||

| + | |style="background:ivory;"|<center>90</center> | ||

| + | |style="background:ivory;"|<center>Commonly cited minimum safe value for the lowest target blood sugar of the day when insulin-controlled. </center> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |style="background:ivory;"|<center>5.5–10</center> | ||

| + | |style="background:ivory;"|<center>100–180</center> | ||

| + | |style="background:ivory;"|<center>Commonly used target range for diabetics, for as much of the time as possible.<ref name ="Valley">{{Cite web|url=http://www.valleyanimalhospital.com/FYI%20Articles/FYI%20Articles%202.htm |title=Diabetes for Dummies-Why is it Critical to Keep Glucose at 80-200|author=Valley Animal Hospital|publisher=Valley Animal Hospital|accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref></center> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |style="background:lemonchiffon;"|<center>10</center> | ||

| + | |style="background:lemonchiffon;"|<center>180</center> | ||

| + | |style="background:lemonchiffon;"|<center> [[Glycosuria|Renal threshold]] for dogs when excess glucose in the blood spills into the urine.<br>The kidneys are unable to reabsorb it all; corresponding diabetic [[Diabetes in dogs#Symptoms|symptoms]] appear.<ref name="Diabetes">{{Cite web|url=http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/40302.htm |title=Diabetes Mellitus|author=Merck Veterinary Manual|publisher=Merck|accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref><ref name ="Regulating"/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.vetsulin.com/vet/AboutDiabetes_Patho.aspx|title=Pathogenesis|publisher=Intervet|accessdate=8 January 2011}}</ref></center> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |style="background:lemonchiffon;"|<center>14</center> | ||

| + | |style="background:lemonchiffon;"|<center>250</center> | ||

| + | |style="background:lemonchiffon;"|<center> Approximate maximum safe value for the highest blood sugar of the day.<ref name = "AAHA"/><br> Dogs can form [[cataracts]] at this level and need to be checked for [[ketones]] using [[Clinistrip|urine strips]].<ref name ="Davis">{{Cite web|url=http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/medicalschool/centers/BarbaraDavis/Documents/book-understandingdiabetes/ud05.pdf|title=Understanding Diabetes-Chapter 5, Ketone Testing (page 30)|author=Chase, Peter|publisher=Barbara Davis Center for Diabetes|accessdate=17 March 2010}} ([[PDF]])</ref><br> Higher blood glucose levels indicate a lack of sufficient insulin.<br> The body can switch from using ketones instead of glucose for fuel.<ref name = "Hanas">{{Cite web|url=http://www.childrenwithdiabetes.com/download/hanas_pump.pdf|title= Insulin Dependent Diabetes in Children, Adolescents and Adults (page 11)|year=1999|author=Hanas, Ragnar |publisher=Children With Diabetes|accessdate=17 March 2010}} ([[PDF]])</ref></center> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |style="background:lemonchiffon;"|<center>16.7</center> | ||

| + | |style="background:lemonchiffon;"|<center>300</center> | ||

| + | |style="background:lemonchiffon;"|<center>Ketone monitoring is needed at this level.<br>High blood glucose values increase the risk of the body switching to using ketones for energy.<ref name = "Hanas" /></center> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !style="background:mistyrose;"|<center>>20</center> | ||

| + | !style="background:mistyrose;"|<center>>360</center> | ||

| + | !style="background:mistyrose;"|<center>Ketones need frequent monitoring due to the increasing insulin deficit illustrated by high glucose readings.<br>As blood glucose values increase, so does the possibility for ketone production.<ref name = "Hanas" /><br>Both short and long-term ill effects are possible-see [[hyperglycemia]] for details. </center> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | </center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Disease complications== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Ketones – ketoacidosis=== | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" width="400" align="right" border="2" cellpadding=2 style="border-collapse:collapse" | ||

| + | !align="center" colspan="2" style="background:#BCD2EE;"| '''Ketone Monitoring Needed:''' | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !align="center" colspan="2" style="background:ivory;"|[[Hyperglycemia|High]] [[blood sugar]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !align="center" colspan="2" style="background:ivory;"|over 14 mmol/L or 250 mg/dL | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !align="center" colspan="2" style="background:ivory;"|[[Dehydration]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !align="center" colspan="2" style="background:ivory;"|skin does not snap back into place quickly<br>after being gently pinched; gums are tacky or dry<ref name="Assessing">{{Cite web|url=http://www.peteducation.com/article.cfm?c=1+2144&aid=1161 |title=Assessing Dehydration Through Skin Elasticity|publisher=Drs. Foster & Smith-Pet Education|accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref><ref name="Water">{{Cite web|url=http://www.peteducation.com/article.cfm?cls=2&cat=1661&articleid=716 |title=Water: A Nutritional Requirement|publisher=Drs. Foster & Smith-Pet Education.com|accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !align="center" colspan="2" style="background:ivory;"|Not eating for over 12 hours | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !width="200" style="background:ivory;" align="center"|[[Vomiting]] | ||

| + | !width="200" style="background:ivory;" align="center"|[[Lethargy]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !width="200" style="background:ivory;" align="center"|Infection or illness<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.novonordisk.com.au/Diabetes_Graphics/2008files/Ketosis_Page_08.pdf |title=Ketosis|publisher=Novo Nordisk|accessdate=17 April 2010}} ([[PDF]])</ref> | ||

| + | !width="200" style="background:ivory;" align="center"|High stress levels | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !align="center" colspan="2" style="background:ivory;"|Breath smells like acetone (nail-polish remover) or fruit.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/complications/ketoacidosis-dka.html|title=Diabetes Complications-Ketoacidosis|publisher=American Diabetes Association|accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Ketone bodies|Ketones]] in the urine or blood, as detected by [[clinistrip|urine strips]] or a blood ketone testing meter, may indicate the beginning of [[diabetic ketoacidosis]] (DKA), a dangerous and often quickly fatal condition caused by high glucose levels ([[hyperglycemia]]) and low insulin levels combined with certain other systemic stresses.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.childrenwithdiabetes.com/d_0i_191.htm |title=Blood Ketone Testing Meter--Abbott's Precision Xtra|publisher=Children With Diabetes|accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref><ref name = "Hanas2">{{Cite web|url=http://www.childrenwithdiabetes.com/presentations/06-cwd-sick-days_files/frame.htm#slide0619.htm|title= Ketones Increase With Lack of Insulin|author=Hanas, Ragnar|publisher=Children With Diabetes|accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref> DKA can be arrested if caught quickly. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ketones are produced by the liver as part of fat metabolism and are normally not found in sufficient quantity to be measured in the urine or blood of non-diabetics or well-controlled diabetics.<ref name = "Schall" /> The body normally uses glucose as its fuel and is able to do so with sufficient insulin levels. When glucose is not available as an energy source because of untreated or poorly treated diabetes and some other unrelated medical conditions, it begins to use fat for energy instead. The result of the body turning to using fat instead of glucose for energy means ketone production that is measurable when testing either urine or blood for them.<ref name = "Hanas" /><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.patient.co.uk/doctor/Urine-Ketones-What-They-Mean-and-False-Positives.htm|title=Urine Ketones-Meanings and False Positives|publisher=Patient UK|accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://ahdc.vet.cornell.edu/clinpath/modules/ua-rout/KETSTIX.HTM|title=Urine Ketones|publisher=Cornell University|accessdate=25 August 2010}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ketone problems that are more serious than the "trace or slight" range need immediate medical attention; they cannot be treated at home.<ref name=Meisler>{{cite web|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sqXlv3FTU3o&feature=PlayList&p=F8B6627A7C08C6BF&index=15 |publisher=YouTube|title=Diabetes in Dogs|author=Meisler, Sam}}</ref> Veterinary care for [[ketosis]]/ketoacidosis can involve intravenous (IV) fluids to counter [[dehydration]],<ref name="Schall"/><ref name = "Endocrine" /> when necessary, to replace depleted [[Electrolyte#Physiological importance|electrolytes]],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.rxed.org/rxtech/ce/tech-insulin.htm |title=Hypokalemia-Low Blood Potassium|publisher=RxEd|accessdate=17 April 2010 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20070820011317/http://www.rxed.org/rxtech/ce/tech-insulin.htm |archivedate = 20 August 2007}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|title=Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus in Dogs and Cats|author=Schermerhorn, Thomas|year=2008|work=North American Veterinary Conference (NAVC)}}</ref><ref name="Electrolytes">{{Cite web|url=http://www.medicinenet.com/electrolytes/article.htm |title=What Are Electrolytes?|author=Stoeppler, Melissa Conrad|publisher=MedicineNet|accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|title=Electrolytes, Fluids and the Acid-Base Balance|date=February 2001|work=Veterinary Technician|author=Wortinger, Ann}}</ref> [[intravenously|intravenous]] or [[intramuscularly|intramuscular]]<ref name="Herrtage"/> [[Insulin therapy#Types|short-acting]] insulin to lower blood glucose levels,<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=12219720 |title=Critical Care Monitoring Considerations for the Diabetic Patient-Clinical Techniques in Small Animal Practice|year=2002|author=Connally, H.E.|publisher=Clinical techniques in small animal practice|accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=pubmed&cmd=Retrieve&dopt=AbstractPlus&list_uids=6790505&query_hl=1&itool=pubmed_DocSum |title=Low-dose Intramuscular Insulin Therapy for Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Dogs|year=1981|author=Chastain, C.B.|author2=Nichols, C.E.|publisher=Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association|accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref> and measured amounts of glucose or force feeding, to bring the metabolism back to using glucose instead of fat as its source of energy.<ref name = "Herrtage">{{Cite web|url=http://www.vin.com/proceedings/Proceedings.plx?CID=WSAVA2009&Category=8060&PID=53521&O=Generic |title=New Strategies in the Management of Canine Diabetes Mellitus|year=2009 |author=Herrtage, Michael|publisher=World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA)|accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref><ref name = "Diabetes"/><ref>{{cite journal|title=Canine Ketoacidosis|author=Huang, Alice, Scott-Moncrieff, J. Catherine|work= Clinician's Brief|date=April 2011}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Ketostix chart.jpg|250px|thumb|left|'''Ketostix''' color chart for interpreting test results. This test measures '''only ketones''' in urine.]] | ||

| + | When testing urine for ketones, the sample needs to be as fresh as possible. Ketones evaporate quickly, so there is a chance of getting a false negative test result if testing older urine.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.vet.uga.edu/VPP/clerk/Sine/index.php |title=Urinalysis Dipstick Interpretations|author=Sine, Cheryl S.|coauthors=Krimer, Paula, et al.|publisher=University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine|accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref> The urine testing strip bottle has instructions and color charts to illustrate how the color on the strip will change given the level of ketones or glucose in the urine over 15 (ketones–Ketostix) or 30 (glucose–Ketodiastix) seconds.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.diabetesselfmanagement.com/pdfs/pdf_1725.pdf |title=Ketone Strips|publisher=Diabetes Self-Management|accessdate=17 April 2010}} ([[PDF]])</ref> Reading the colors at those time intervals is important because the colors will continue to darken and a later reading will be an incorrect result.<ref name = "Hanas2"/> Timing with a clock or watch second hand instead of counting is more accurate.<ref name ="Davis" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | At present, there is only one glucometer available for home use that tests blood for ketones using special strips for that purpose–Abbott's Precision Xtra.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.abbottdiabetescare.com/precision-xtra-blood-glucose-and-ketone-monitoring-system.html |title=Abbott's Precision Xtra|publisher=Abbott Diabetes Care|accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1111/j.1939-1676.2009.0302.x|title=Evaluation of a Portable Meter to Measure Ketonemia and Comparison with Ketonuria for the Diagnosis of Canine Diabetic Ketoacidosis|author= Di Tommaso, M., Aste, G., Rocconi, F., Guglielmini, C., Boari, A. |year=2009|publisher=Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine}}</ref> This meter is known as Precision, Optium, or Xceed outside of the US.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.prnewswire.co.uk/cgi/news/release?id=129328 |title=Abbott's Precision/Optium/Xceed|author=Abbott Diabetes Care|publisher=PRNewswire|accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://yorkshirediabetes.com/patients/meters.php?rec=51&detail=y |title=Abbott Optium Xceed|publisher=Yorkshire Diabetes|accessdate=17 March 2010|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20090210193751/http://yorkshirediabetes.com/patients/meters.php?rec=51&detail=y|archivedate=10 February 2009}}</ref> The blood ketone test strips are very expensive; prices start at about US$50 for ten strips.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.amazon.com/dp/B001EL30TM |title=Precision Xtra Blood Ketone Test Strips|author=Abbott Diabetes Care|publisher=Abbott Diabetes Care|accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref> It is most likely urine test strips–either ones that test only for ketones or ones that test for both glucose and ketones in urine would be used. The table above is a guide to when ketones may be present. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Nonketotic hyperosmolar syndrome=== | ||

| + | Nonketotic hyperosmolar syndrome (also known as hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome) is a rare but extremely serious complication of untreated canine diabetes that is a medical emergency. It shares the symptoms of extreme hyperglycemia, dehydration, and lethargy with ketoacidosis; because there is some insulin in the system, the body does not begin to turn to using fat as its energy source and there is no ketone production.<ref name=Endocrine/> There is not sufficient insulin available to the body for proper uptake of glucose, but there is enough to prevent ketone formation. The problem of dehydration in NHS is more profound than in diabetic ketoacidosis.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.vetsulin.com/vet/Diagnosis_Hyperosmolar.aspx |title=Treating hyperosmolar syndrome |publisher=Intervet|accessdate=20 June 2011}}</ref> Seizures and coma are possible.<ref name=Crises>{{cite web |url=http://veterinarycalendar.dvm360.com/avhc/article/articleDetail.jsp?id=567269&sk=&date=&pageID=2|title=Diabetic crises: Recognition and management (Proceedings)|author=Macintyre, Douglass|date=1 August 2008|publisher=DVM 360|accessdate=20 June 2011}}</ref> Treatment is similar to that of ketoacidosis, with the exceptions being that NHS requires that the blood glucose levels and rehydration be normalized at a slower rate than for DKA; [[cerebral edema]] is possible if the treatment progresses too rapidly.<ref name=Endocrine/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Dehydration==== | ||

| + | {|class="wikitable" align="right" width="500" border="1" style="border-collapse:collapse" bgcolor="powderblue"| | ||

| + | ! colspan="2" style="background:#BCD2EE" |Clinical Signs of Dehydration <ref name="Dehydration"/> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! colspan="2" style="background:#cae1ff" |Based on percentage of body weight, not percentage of fluid loss | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! width="250" style="background:#BCD2EE;" align="center"|< 5% (mild) | ||

| + | ! width="250" style="background:ivory;" align="center"|not detectable | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! width="250" style="background:#BCD2EE;" align="center"|5–6% (moderate) | ||

| + | !width="250" style="background:ivory;" align="center"|slight loss of [[Elasticity (physics)|skin elasticity]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! colspan="2" style="background:#BCD2EE"|6–8% (moderate) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! width="250" style="background:ivory;" align="center"|definite loss of skin elasticity | ||

| + | !width="250" style="background:ivory;" align="center"|slight prolongation of [[capillary refill]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! width="250" style="background:ivory;" align="center"|slight sinking of eyes into [[Orbit (anatomy)|orbit]] | ||

| + | !width="250" style="background:ivory;" align="center"|slight dryness of [[Oral mucosa|oral mucous membranes]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! colspan="2" style="background:lemonchiffon" align="center"|10–12% (marked)–emergency | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !colspan="2" style="background:ivory;" align="center"|tented skin stands in place | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !width="250" style="background:ivory;" align="center"|prolonged capillary refill | ||

| + | !width="250" style="background:ivory;" align="center"|eyes sunken in orbits | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !width="250" style="background:ivory;" align="center"|dry mucous membranes | ||

| + | !width="250" style="background:ivory;" align="center"|possible signs of [[Shock (circulatory)|shock]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! colspan="2" style="background:mistyrose"|12–15% signs of hypovolemic shock, death–emergency<ref name="Hypovolemic"/> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Body fluid loss is measured in two major ways–sensible and insensible. Sensible is defined as being able to be measured in some way; vomiting, urination and defecation are all considered to be sensible losses as they have the ability to be measured. An insensible loss example is breathing because while there are some fluid losses, it is not possible to measure the amount of them.<ref name="Dehydration">{{Cite web|url=http://www.vetmed.wsu.edu/courses_vm551_crd/notes/fluidrx_text.asp |title=Assessing Dehydration Status|publisher=Washington State University|accessdate=21 August 2010 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20080724031447/http://www.vetmed.wsu.edu/courses_vm551_crd/notes/fluidrx_text.asp |archivedate = 24 July 2008}}</ref> With a condition like fever, it is possible to measure the amount of fluid losses from it with a formula that increases by 7% for each degree of above normal body temperature, so it would be classed as a sensible loss.<ref name="Fluid">{{Cite web|url=http://courses.vetmed.wsu.edu/vm551_crd/notes/fluidFacts.asp |title=Fluid Facts|publisher=Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine|accessdate=21 August 2010|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20060904045751/http://courses.vetmed.wsu.edu/vm551_crd/notes/fluidFacts.asp|archivedate=4 September 2006}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | A check of the pet's gums and skin can indicate dehydration; gums are tacky and dry and skin does not snap back quickly when pinched if dehydration is present.<ref name="Assessing"/><ref name="Water"/><ref name="Dehydration"/> When the skin at the back is lifted, a dehydrated animal's does not fall back into place quickly. Serious dehydration (loss of 10–12% of body fluids) means the pulled up skin stays there and does not go back into place. At this point, the animal may go into shock; dehydration of 12% or more is an immediate medical emergency.<ref name="Fluid"/> Hypovolemic shock is a life-threatening medical condition in which the heart is unable to pump sufficient blood to the body, due to loss of fluids.<ref name="Hypovolemic">{{Cite web|url=http://www.umm.edu/ency/article/000167.htm|title=Hypovolemic shock|publisher=University of Maryland Medical Center|accessdate=21 August 2010}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Dehydration]] can change the way [[Subcutaneous injection|subcutaneous]] insulin is absorbed, so either hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia are possible; dehydration can also cause false negative or positive urine ketone test results.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.acep.org/webportal/membercenter/sections/peds/quizzes/0304ans.htm |title=Pediatric Endocrine Emergency Answer Sheet|publisher=American College of Emergency Physicians|accessdate=21 August 2010 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20070320064405/http://www.acep.org/webportal/membercenter/sections/peds/quizzes/0304ans.htm |archivedate = 20 March 2007}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|title=Ketosis and Dehydration|year=2003|work=North American Veterinary Conference}}</ref> Hyperglycemia means more of a risk for dehydration.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.faqs.org/nutrition/Hea-Irr/Hyperglycemia.html |title=Hyperglycemia|publisher=FAQS.org|accessdate=21 August 2010}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Treatment complications== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Hypoglycemia=== | ||

| + | Hypoglycemia, or low blood glucose, can happen even with care, since insulin requirements can change without warning. Some common reasons for hypoglycemia include increased or unplanned exercise, illness, or medication interactions, where another medication [[wiktionary:potentiate|potentiates]] the effects of the insulin.<ref name = "Emergencies" /><ref name = "Foster" /> [[Vomiting]] and [[diarrhea]] episodes can bring on a hypoglycemia reaction, due to dehydration or simply a case of too much insulin and not enough properly digested food.<ref name = "Vetsulin">{{Cite web |url=http://www.vetsulin.com/vet/AboutDiabetes_Glucose.aspx |title=Hypoglycemia |author=Vetsulin|publisher=Intervet |accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref><ref name="UK">{{Cite web |url=http://www.cat-dog-diabetes.com/dogs-hypoglycaemia.asp |title=Hypoglycaemia|author=Cat-Dog-Diabetes|publisher= Intervet (UK) |accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref> Symptoms of hypoglycemia need to be taken seriously and addressed promptly. Since serious hypoglycemia can be fatal, it is better to treat a suspected incident than to fail to respond quickly to the signs of actual hypoglycemia.<ref name="Pierce"/><ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.novonordisk.com.au/Diabetes_Graphics/2008files/HypoPages_08.pdf |title=Hypoglycemia|publisher=Novo Nordisk|accessdate=17 April 2010}} ([[PDF]])</ref><ref name = "Jasmine">{{cite web|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XAZxhIGNnY4 |publisher=YouTube |title=video of Jasmine, a canine diabetic, showing signs of hypoglycemia that progress into a hypoglycemic seizure}}</ref> Dr. Audrey Cook addressed the issue in her 2007 article on diabetes mellitus: "Hypoglycemia is deadly; hyperglycemia is not. Owners must clearly understand that too much insulin can kill, and that they should call a veterinarian or halve the dose if they have any concerns about a pet's well-being or appetite. Tell owners to offer food immediately if the pet is weak or is behaving strangely."<ref name ="AAHA"/><ref name = "Cook" /><ref>{{Cite web |url=http://veterinarymedicine.dvm360.com/vetmed/data/articlestandard//vetmed/372007/456192/i3.gif |title=What Clients Need to Know |year=2007|author=Cook, Audrey|publisher=DVM 360|accessdate=17 March 2010}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Symptoms==== | ||

| + | Some common symptoms are:<ref name = "Emergencies">{{Cite web|url=http://www.vetsulin.com/dog-owner/Emergencies.aspx |title=Emergencies-Low Blood Sugar|author=Vetsulin|publisher=Intervet|accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref><ref name = "Vetsulin" /><ref name = "Jasmine" /> | ||

| + | *depression or lethargy | ||

| + | *confusion or dizziness | ||

| + | *trembling<ref name=Long>{{Cite web|url=http://www.walthamusa.com/articles/wf103fle.pdf |title=Long-Term Management of the Diabetic Dog|author=Fleeman, Linda|author2=Rand, Jacqueline|year=2000|publisher=Waltham USA|accessdate=17 April 2010}} ([[PDF]])</ref> | ||

| + | *weakness<ref name = "Foster">{{Cite web|url=http://www.peteducation.com/article.cfm?c=2+2097&aid=3587|title=Hypoglycemia|publisher= Drs. Foster & Smith Pet Education|accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref> | ||

| + | *ataxia (loss of coordination or balance) | ||

| + | *loss of excretory or bladder control (sudden house accident) | ||

| + | *vomiting, and then loss of consciousness and possible seizures<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.vetmed.wsu.edu/ClientED/seizures.aspx |title=Seizures|publisher=Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine|accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Successful home treatment of a hypoglycemia event depends on being able to recognize the symptoms early and responding quickly with treatment.<ref name = "Foster" /> Trying to make a seizing or unconsicous animal swallow can cause choking on the food or liquid. There is also a chance that the materials could be [[Aspiration pneumonia|aspirated]] (enter the lungs instead of being swallowed).<ref name = "Emergencies"/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/121615.htm&word=aspiration|title=Pneumonia|publisher=Merck Veterinary Manual|accessdate=19 April 2011}}</ref> Seizures or loss of consciousness because of low blood glucose levels are medical emergencies.<ref name = "Emergencies" /><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.canine-epilepsy.com/underlying.html#anchor700068 |title=Hypoglycemia|author=Thomas, WB|publisher=University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine|accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Treatment==== | ||