Toxoplasmosis - Sheep

| This article is still under construction. |

Description

Toxoplasmosis is the disease caused by Toxoplasma gondii, an intracelluler protozoan parasite. Although the definitive host is the cat, T. gondii can infect all mammals including man and is a significant cause of abortion in sheep and goats. Toxoplasmosis does not seem to cause disease in cattle.

Life Cycle

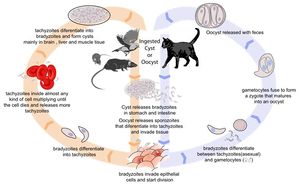

There are three infectious stages of Toxoplasma gondii: 1) sporozoites; 2) actively reproducing tachyzoites; and 3) slowly multiplying bradyzoites. Tachyzoites and bradyzoites are found in tissue cysts, whereas sporozoites are containted within oocysts, which are excreted in the faeces. This means that the protozoa can be transmitted by ingestion of oocyst-contaminated food or water, or by consumption of infected tissue.

In naive cats, Toxoplasma gondii undergoes an enteroepithelial life cycle. Cats ingests intermediate hosts containing tissue cysts, which release bradyzoites in the gastrointestinal tract. The bradyzoites penetrate the small intestinal epithelium and sexual reproductio ensues, eventually resulting the production of oocysts. Oocysts are passed in the cat's faeces and sporulate to become infectious once in the environment. These can then be ingested by other mammals, including sheep.

When sheep ingest oocysts, T.gondii intiates extraintestinal replication. This process is the same for all hosts, and also occurs when carnivores ingest tissue cysts in other animals. Sporozoites (or bradyzoites, if cysts are consumed) are released in the intestine to infect the intestinal epithelium where they replicate. This produces tachyzoites, which reproduce asexually within the infected cell. When the infected cell ruptures, tachyzoites are released and disseminate via blood and lymph to infect other tissues. Tachyzoites then replicate intracellularly again and the process continues until the host becomes immune or dies. If the infected cell does not burst, tachyzoites eventually encyst as bradyzoites and persist for the life of the host. Cyst are most commonly found in the brain or skeletal muscle, and are a source of infection for carnivorous hosts.

Transmission to Sheep

Oocysts in the Environment

As the definitive hosts of Toxoplasma gondii, cats become infected when they hunt and eat infected wild rodents and birds. Rodents are a particularly important source of feline infection, as they can pass T. gondii infection to their offspring without causing clinical disease. This means that a farm may develop a reservoir of T. gondii tissue cysts with the potential to cause feline infection and massive oocyst excretion when a cat is introduced to the environment. Between days 3 and 14 post-infection, cats shed over 100 million of oocysts in their faeces. Studies have shown an association between ovine toxoplasma infection, and the contamination of feed or grazing with sporulated oocysts1, highligting the importance of oocysts as a source of infection for sheep. It has also been demonstrated that the prevalence of ovine toxoplasmosis varies with the presence of cats on a farm2.

Congenital Transmission

Apart from ingestion of oocysts in the environment, the only other method of transmission of toxoplasmosis to sheep is vertical spread from mother to foetus during pregnancy. This is because sheep are herbivorous, and do not consume animal tissues containing cysts. The outcome of transplacental infection depends on the stage of pregnancy. Infection in early gestation usually causes foetal death, as the foetal immune system is immature at this stage. In mid-gestation, infection may cause the birth of weak or stillborn lambs, sometimes accompanied by a mummified sibling. Ewes infected in the third trimester normally give birth to infected but clinically normal lambs.

Signalment

Ovine toxoplasmosis is only clinically apparent when primary infection of a pregnant animal occurs.

Diagnosis

A combination of clinical signs and (histo)pathology are most commonly used to make a diagnosis of ovine toxoplasmosis, but serology may be of use in some cases.

Clinical Signs

The signs of toxoplasmosis in sheep manifest following the exposure of a naive pregnant ewe to oocysts. The sporozoites ingested excyst in the digestive tract and penetrate the intestinal epithelium, before reaching the mesenteric lymph nodes around day 4 post-infection. Here, they cause lymphomegaly and focal necrosis before contributing to a parisitaemia from day 5. Pyrexia is associated with the development of parasitaemia.

Following dissemination of T. gondii in the blood, many tissues become infected. Parasitaemia ends when the maternal immune response becomes effective, and protozoa start to encyst as bradizoites. In pregnant animals, the uterus is an immunoprivileged site, and the outcome of foetal infection is influenced by the stage of gestation. In early pregnancy, the foetus is unable to mount any immune response, and so cannot inhibit parasite multiplication. The foetus rapidly dies and is resorbed. In a flock, this is visable clinically as large numbers of barren ewes. In mid-gestation (70-120 days), infection can again be fatal. This causes a mummified foetus which is often twinned with a lamb that is stillborn or weak. Abortion due to infection at 70-120 days gestation tends to occur in very late pregnancy. Because the foetal immune system is well developed in late pregnancy, infection at this stage will be resisted, and the lamb will be born transiently infected but alive.

Laboratory Tests

Anti-Toxoplasma gondii IgG antibodies can be detected in the maternal circulation from thirty days post-infection and remain increased for years afterwards. This means that for clinical diagnosis, IgG titres must be measured in paired serum samples taken 3-4 weeks apart, and must show at least a four-fold increase in titre3. In an outbreak of disease, this time scale may be too great to be useful. IgM antibodies become apparent sooner after infection and persist for a much shorter time, and so increased IgM titres are consistent with recent infection.

Pathology

Multiplication of Toxoplasma gondii in the placeneta causes multiple foci of necrosis, which limit effective function during pregnancy. After birth, these areas of necrosis are visible as white spots on the cotyledons. The intercotyledonary areas appear normal.

Histologically, foetal tissues may display changes. In the brain, glial foci surround a necrotic centre and represent a foeal immune response to damage initiated by parasite multiplication. An associated mild lymphoid meningitis is often seen. Focal leukomalacia is also common and is thought to be due to foetal anoxia in late gestation, caused by extensive necrosis of the placentome. Focal inflammatory lesions with diffuse lymphoid infiltrates can be found in many other tissues, including the liver, lung and heart. The kidneys and skeletal muscle are less frequently affected.

Treatment

- Toxovax vaccine

- Live, avirulent strain of Toxoplasma

- Does not form bradyzoites or tissue cysts

- Killed by host immune system

- Single dose given 6 weeks before tupping

- Protects for 2 years

- Immunity boosted by natural challenge

- Medicated feed can be given daily during the main risk period

- 14 weeks before lambing

- The best method of protection is to prevent cats from contaminating the pasture, lambing sheds and feed stores

The extent of environmental contamination with T. gondii oocysts is thus related to the distribution and behaviour of cats. Measures to reduce environmental contamination by oocysts should be aimed at reducing the number of cats capable of shedding oocysts. This would include attempts to limit their breeding. If male cats are caught, neutered and returned to their colonies the stability ofthe colony is maintained; fertile male cats do not challenge the neutered males12 and breeding is controlled. Thus the maintenance ofa small healthy population of mature cats will reduce oocyst excretion as well as help to control rodents. Sheep feed should be kept covered at all times to prevent its contamination by cat faeces.

Prognosis

Links

References

- Plant, J Wet al (1974) Toxoplasma infection and abortion in sheep associated with feeding of grain contaminated with cat faeces. Australian Veterinary Journal, 50, 19–21.

- Skjerve, E et al (1998). Risk factors for the presence of antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in Norwegian slaughter lambs. Preventative Veterinary Medicine, 35, 219–227.

- Buxton, D (1990) Ovine toxoplasmosis: a review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 83, 509-511.

- Innes, E A et al (2009) Ovine toxoplasmosis. Parastiology, 136, 1887–1894.

- Buxton, D et all (2007) Toxoplasma gondii and ovine toxoplasmosis: New aspects of an old story. Veterinary Parasitology, 147, 25-28.

- Dubey, J P (2009) Toxoplasmosis in sheep — The last 20 years. Veterinary Parasitology, 163, 1-14.