Hyperlipaemia - Donkey

Introduction

Hyperlipaemia is a life-threatening disease to which donkeys are particularly prone, both as a primary or secondary condition. The metabolic pathways are complex, involving many factors. Basically, hyperlipaemia occurs when animals mobilise triglyceride from body fat reserves in response to a negative energy balance achieving plasma levels over 5 mmol per litre. The end result is multi-organ failure as lipid is deposited in the liver and kidneys. The initial clinical signs are easy to miss, especially in donkeys and, if early treatment is not initiated, the disease will progress rapidly to terminal stages.

Signalment

Hyperlipaemia is a common complication of any stress, management change or illness. Early detection and treatment are essential as, in the latter stages, mortality rates are high. Obese animals are at higher risk, but any donkey can be affected.

Risk Factors

- Body condition:

The prevalence of the disease in fat and obese animals is higher than in normal and thin animals, due to higher body fat reserves and to increased insulin resistance. - Stress:

Donkeys are more susceptible to hyperlipaemia at times of stress, such as transportation or changes in environment, management or their social group. - Age:

Younger animals are less prone to the disease than animals over ten years, possibly due to better health and strength. - Sex:

Mares are more likely to get the disease than males, due to aspects of their physiology. Gender does not significantly affect survival. - Late pregnancy and early lactation:

The additional energy demand on the mare during these periods increases the risk of developing hyperlipaemia. - Cushing’s Syndrome:

Cortisol antagonises the effect of insulin, which allows body fat to be more readily mobilised. - Laminitis:

Primary hyperlipaemia can be seen in laminitic animals, due to the association with insulin resistance. The disease can be secondary, due to inappetence. - Concurrent disease:

Any disease that puts the animal in a negative energy balance can cause hyperlipaemia, such as:- Chronic renal failure

- Gastro-intestinal diseases, specifically parasitism, colitis, gastric ulceration, impactions and any cause of dysphagia

- Hepatopathy

- Dental disease

- Endotoxaemia

- Neoplasia

- Surgery:

The starvation period prior to surgery, added to the possible period of inappetence that follows, involves significant fasting of an animal, especially in the case of abdominal surgery. With the added effect of the stress involved, due to change in management, handling for medication and likely pain, surgical cases are at high risk of secondary hyperlipaemia.

Pathogenesis

Only recently has it been understood that two conditions must apply for the body to fail to control the lipid circle of synthesis, utilisation and storage:

- Energy requirement leading to the mobilisation of body fat stores by hormone-sensitive lipase.

- Failure of insulin to block the action of hormone-sensitive lipase once the body’s energy demand is met.

Free fatty acids (FFA) are then released into the bloodstream in quantities that exceed the liver’s pathways of oxidation, glucogenesis and ketogenesis. The FFAs are re-esterified by the liver to form triglycerides (TGs) and released back into the plasma as very low-density lipoproteins (VLDLs).

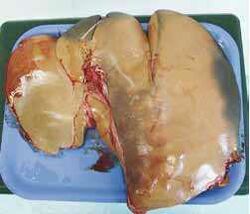

This circle will continue if the energy demand and insulin resistance persists, leading to impaired liver function and eventual hepatic failure.

Insulin resistance is exacerbated by obesity, pregnancy and stress (Jeffcott and Field, 1985). See illustration

To aid the removal of the lipid from the blood, stress must be reduced or avoided, and the negative energy balance must be reversed, providing the liver is not irrevocably damaged.

Diagnosis

Clinical Signs

Early clinical signs are often vague and easily missed. Due to the predisposition of donkeys to hyperlipaemia, any animal included in one or more of the risk factors should be monitored closely and, ideally, receive preventative treatment.

The behavioural changes may be very subtle in a quiet, stoical donkey. To diagnose hyperlipaemia, a thorough clinical examination is required, including serum biochemistry to assess hyperlipidaemia. Hyperlipaemia should always be considered when a dull or sick donkey is presented. The donkey owner’s opinion of the demeanour is valuable in detection of these early changes. The condition will progress rapidly if unchecked, to include one or more of the following clinical signs:

• Inappetence/anorexia

• Gut stasis with diagnostic mucus-covered, dry faecal balls

• Halitosis – characteristic smell associated with the ileus

• Congested mucous membranes with delayed capillary refill time

• Pyrexia – more likely associated with a primary condition

• Ataxia

• Tachycardia

• Tachypnoea

• Ventral oedema associated with hypoalbuminaemia

• Hepatic encephalopathy

• Abdominal pain: may be evident but thorough rectal examination is risky if the rectal mucosa is dry and tacky

The most useful indicator is obviously the appetite. Refusal of treats is almost diagnostic in a greedy animal. Beware of ‘sham’ eating and drinking, that is, ensure the feed is actually being consumed, as a donkey can eagerly attack a bucket of food, giving the appearance of eating while not actually doing so.

Laboratory Tests

Visual assessment of serum is the most valuable diagnostic sign. Leave the plain blood tube upright to settle following jugular sampling. Three to ten minutes later it should be possible to diagnose hyperlipidaemia. Triglycerides (TGs) over 5 mmol per litre should show increasing depth of ‘milky’ serum corresponding to the concentration of fat in the blood.

Prompt treatment can be given, initiated on the suspicion of hyperlipaemia, whilst an underlying cause is sought with a thorough clinical examination, including dental examination using a gag, and rectal examination.

Serum biochemistry and routine haematology should be carried out. This will allow assessment of hydration, liver and kidney function, white blood cell ratios and electrolytes.

Treatment

Basic principles

- Treat any underlying or concurrent diseases

- Fluid therapy:

- Maintain circulatory volume

- Correct any electrolyte abnormalities

- Restore acid/base balance, especially in cases showing renal or hepatic impairment

- Symptomatic therapy:

- NSAIDs, analgesics, anti-ulcer medication

- Multivitamins, anabolics

- Antibiotics

- Nutritional support: maintain a positive energy balance

- Normalise lipid metabolism:

- Reduce mobilisation of plasma triglycerides – insulin (but not commonly done, see below) and glucose

- Increase clearance of plasma triglycerides – heparin (unproven)

Considerations

- Severity of disease

- Voluntary food intake: encourage eating at all times with access to fresh grass and tasty feed. Complete anorexia is related to a worse prognosis.

- Ileus: nasogastric intubation can be used to stimulate gut activity but must not be repeated if stasis continues.

- Response to treatment: TGs reducing/static/increasing.

- Patient compliance: the stress of persisting with treatment can cause a vicious cycle of the syndrome in donkeys that resent handling. Adjust the approach to treatment depending on the individual.

- Economics: intensive i.v. fluid therapy is very expensive. Consider the prognosis before running up large bills. If there is an underlying, untreatable condition, such as dental disease, euthanasia may be the preferred option.

| Plasma triglyceride | Approach to treatment | Prognosis |

| 5-8 mmol/l | Encourage voluntary feeding or tempting, succulent foods, grazing | Values should quickly return to normal if feeding continues |

| 8-10 mmol/l | Nasogastric intubation | Good |

| 10-15 mmol/l | Nasogastric intubation +/- i.v. fluids | Fair if results are reduced promptly. Treat seriously. |

| 15-20 mmol/l | Nasogastric intubation and i.v. fluids | Guarded |

| Over 15-20 mmol/l | Intensive i.v. fluids | Poor |

Treatment

The treatment consists of supportive therapy, drenching or stomachtubing, as well as the administration of intravenous fluids, depending on the severity of the attack. Antibiotics, NSAIDs and drugs to prevent gastric ulcers are usually given.

- NSAID s: Flunixin meglumine as a minimum anti-endotoxic dose

- Corticosteroids: CONTRAINDICATED

- Multivitamins: oral general-use equine multivitamin preparation. Injectable multivitamins can be given but may add to stress.

- Anabolics: Nandrolone Laurate BP can act to stimulate appetite and to counter catabolism.

- Insulin: Protamine zinc insulin can be given but always with glucose. As most cases are likely to be insulin resistant, it is not usual to administer insulin.

- Heparin: theoretically increases the activity of lipoprotein lipase to aid TG clearance, but the enzyme is likely to be working at its maximum, so heparin has little value and the side-effects of haemorrhage cause concern.

- Anti-ulcer drugs: most cases showing inappetence will benefit from anti-ulcer medication as it is a very common finding at post-mortem in elderly or debilitated donkeys.

- Sucralfate, ‘Antepsin’, could be used for prevention

- Ranitidine, ‘Zantac’, is routinely used in oral form. Intravenous injection can be given in a drip.

- Omeprazole, ‘Gastroguard’, is the drug of choice. The drawback is expense.

Fluid therapy

If gut activity is present, fluids are ideally administered via nasogastric intubation with some complete foods, e.g. Ready Brek, Complan, pony nuts or the commercially available enteral feeds. Three to five litres of warm water is ideal with added rehydration salts, e.g. Effydral or Lectade, and 120 g glucose powder (Lectade contains 50 g dextrose). Any other oral medication can be added to save drenching later. This can be repeated twice daily if temperament allows. If sedation is necessary then the side effects may outweigh this method of treatment.

Drenches can be given by the owner, using a 50 ml drenching syringe, and repeating every 4 to 12 hours daily. Dissolve about 100 g glucose in warm, flavoured water, adding multivitamins and other oral medication. Small volumes as often as possible are ideal.

Intravenous fluids are best administered via catheter, 14 g 80 mm. Polyionic fluids with lactate, e.g. Hartmanns, are recommended. Two to three litres given over 45 to 60 minutes, repeated twice daily, is most practical but, administered quickly, diuresis will occur. Ideally fluids should be administered via a curly drip, set continuously over the day. Maintenance is approx 60 ml/kg/day. Five per cent dextrose and Duphalyte are added to the drip.

Parenteral nutrition may become more widely available in the future. This could be useful, but is currently expensive.

Nursing Care

The early signs are subtle behavioural changes, appearing slightly dull and with a reduced appetite. A blood sample should be taken immediately. Milky serum is an indicator of the condition, which will be confirmed by raised triglyceride levels on laboratory analysis.

Keep the donkey eating, hand-feed it and consult the owners with regard to its favourite treats. Turn the donkey out for gentle exercise at grass, or walk in hand, allowing it to browse in the hedgerow. Groom and spend time with the donkey. Early detection and good nursing are important for a successful outcome.

Prognosis

Mortality rates of 60-95% can still be expected. The prognosis improves if the syndrome is detected in the early stages and prompt action is taken to reverse the metabolic affects. Once high plasma triglycerides have been circulating there will be long-term effects due to the accumulation in the organs. Recurrence should be watched for.

The maintenance of gastro-intestinal function is vital if the outcome is to be successful. Early voluntary intake of feed is the best prognostic indicator.

Owners should also be counselled about euthanasia, as terminal cases should not suffer prolonged treatment if the outcome is hopeless.

Prevention

Prevention is definitely better than cure. Bear in mind the increased risk during periods of stress. If any donkey shows a reduced appetite, not even complete inappetence, then a blood sample should be taken to check for gross hyperlipidaemia once it has clotted.

Controlling the weight is also important in prevention, as obese donkeys have a greatly increased risk. Donkeys of condition score 5 and over almost inevitably suffer from hyperlipaemia if stressed by transport, mixing groups, surgery, or even changes in management. Dieting should be done following a strict regime of slow reduction in feed intake. A loss of 2-4 kg per month or 1-2 cm of heart girth is advisable. Owners need to be educated as to the importance of reporting changes in feed intake.

Literature Search

Use these links to find recent scientific publications via CAB Abstracts (log in required unless accessing from a subscribing organisation).

Hyperlipaemia in donkeys publications

References

- Grove, V. (2008) Hyperlipaemia In Svendsen, E.D., Duncan, J. and Hadrill, D. (2008) The Professional Handbook of the Donkey, 4th edition, Whittet Books, Chapter 4

- Dabinett, S. (2008) Nursing care In Svendsen, E.D., Duncan, J. and Hadrill, D. (2008) The Professional Handbook of the Donkey, 4th edition, Whittet Books, Chapter 18

- Fowler, J. N. (1989). The Professional Handbook of the Donkey. Second Edition. E.D. Svendsen (ed). Whittet Books Ltd. pp 108-109.

- Jeffcott, L. N., Field, J. R. (1985). ‘Current Concepts of hyperlipaemia in horses and ponies’. Veterinary Record 116. p 461.

- Mair, T.S. (1995). ‘Hyperlipaemia and laminitis secondary to an injection abscess in a donkey’. Equine Veterinary Education 7 (1). pp 8-11.

- Moore, B.R., Abood, S.K., and Hinchcliffe, K.W. (1994). ‘Hyperlipaemia in 9 miniature horses and miniature donkeys’. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 8. pp 376-381.

- Reid, S. W. J., Cowan, S. J. (1995). ‘Risk factors associated with hyperlipaemia in the donkey’. Equine Veterinary Education 7 (1). pp 22-24.

- Watson, T.D.G. (1998). Metabolic and Endocrine Problems of the Horse. W.B. Saunders, London. pp 23-40.

- Watson, T. D. G., Packard, C. J., Shepherd, J., and Fowler, J. N. (1990). ‘An Investigation of the relationship between body condition and plasma lipid and lipoprotein concentrations in 24 donkeys’. Veterinary Record 127. pp 498-500.

|

|

This section was sponsored and content provided by THE DONKEY SANCTUARY |

|---|