Rats (Laboratory) - Pathology

Introduction

[1] Laboratory rats belong to the species Rattus norvegicus and are bred and kept for scientific research. They are and have been used in experimental studies that have added to our understanding of genetics, disease, pharmacology, psychology and other fields. They originate from wild brown rats. The process of domestication started in Europe during the 18th century, when wild rats were caught for food and rat-baiting. Occasionally, albino rats were trapped and these were kept as pets or show animals. The first time one of these albino mutants was brought into a laboratory for a study was in 1828, in an experiment on fasting. Domestic rats differ from wild rats in that they are calmer, less likely to bite, can tolerate greater crowding, breed earlier and are more prolific. Also, their brains, livers, kidneys, adrenal glands and hearts are smaller.

Strains, Stocks and Transgenics

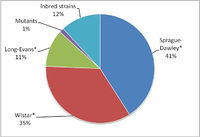

All rat populations used in research can be included in one of these three groups. Figure 1 is based on a PubMed search of the number of papers using the designated strain or stock for the years 2001-2005. The vast majority of work (76%) was done using outbred Sprague-Dawley or Wistar rats. Inbred strains were used on only 12% of occasions. Of the inbred strains, the most widely used was F344 (32.1%), followed by LEW (22.5%). Mutants (=transgenic) were used only in 1% of the studies, reflecting the circumstances explained below.

Stocks (~outbred strains)

A stock is an outbred population (frequently these are termed outbred strains). These are used when identical genotypes are unnecessary or a random population is required. Examples:

- Wistar: First rat stock developed as a laboratory model and still one of the most popular. More than half of all laboratory rat strains are descended from this stock (e.g. Sprague Dawley, Long-Evans). They have wide head, long ears and a tail shorter than the body.

- Sprague Dawley: Multipurpose breed of albino rat used extensively in medical research due to its calmness and ease of handling. They are prolific (average litter: 10.5), with a lifespan of 2.5-3.5 years and a tail longer than the body.

- Long-Evans: Multipurpose model organism (frequent in behavioral and obesity research). Developed by crossing Wistar females with a wild gray male. They are white with a black or brown hood (=head and shoulders).

Strains (~inbred strains)

A strain is a group of organisms of the same species, having distinctive characteristics but not usually considered a separate breed or variety (can be termed inbred strains). This is accomplished through inbreeding with the aim of excluding genetic variation as a factor in experiments. Examples:

- Fisher 344 (F344): Rat model frequently used in cancer research.

- Lewis (lew): Multiuse inbred strain.

- Biobreeding rat: Model for Type 1 diabetes.

- Zucker rat: Model for obesity and hypertension.

- Hairless rats: Different types. Used in research of immunocompromise and genetic kidney diseases:

- Athymic: Rowett nude (rnu).

- Genetic kidney disease: fuzzy (fz) and shorn (shn).

- RCS: Royal College of Surgeons rat, with inherited retinal degeneration.

- Shaking rat Kawasaki: Deficient in cortex lamination and cerebellar development

Transgenic rats

Most of the techniques used for genetic manipulation depend upon the culture and manipulation of embryonic stem cells (eES). eES techniques are relatively difficult in rats compared to mice and for this reason, transgenic rats are not commonly used in scientific research. However, in 2003 researchers succeeded in cloning two laboratory rats by nuclear transfer [2]. and the rat genome is now available [3]. For these reasons, usage of transgenic rats may increase in the near future, as rats are more appropriate models than mice in specific situations. These are the most common types of genetic modification:

- Knock-out animals have a single gene turned off through a targeted mutation (gene trapping). They are mostly used as human disease models, for the study of gene function and for drug discovery and development. The technology for production of knock out rats has evolved significantly during the last years and rat models for the study Parkinson\’s, Alzheimer\’s, hypertension, and diabetes are now available commercially.

- Knock-in animals have a single gene insertion in a specific locus (it is targeted too). This is currently done in mice.

- Conditional Knock-out/in animals have modified genes that can be knocked-out or knocked-in by manipulation of the environment or administration of a drug. This provides researchers with added flexibility in experimental design. Also in this case these manipulations are mostly conducted in mice.

- Random mutagenesis. These techniques are used in the generation of libraries of genetically modified animals. Phenotyping and mutation mapping are time consuming and thousands of mutations are required in a single animal to generate a novel phenotype.

Anatomy and Histology

This summary [4][5] is not comprehensive and it only aims to deal with peculiarities of rat anatomy and histology. The information on gross anatomy is from a reference on F344 rat and minor variations with other strains should be expected:

Nervous system

The brain is lissencephalic. The spinal cord is 11-12.5cm long and ends in the second lumbar vertebra.

Vascular system and blood

The heart of a young adult rat is approximately 0.3% of the body weight. In the blood The predominant leukocyte is the lymphocyte (80%). Eosinophils tend to have ring-shaped nuclei without lobation. Mature male rats have higher leukocyte counts than females

Respiratory system

The trachea is slightly flattened (3mm x 2mm diameter). The lung has a single left lobe and four right lobes that follow the bifurcations of the bronchial tree (anterior (=apical or cranial), middle (=cardiac), median (=azygous or accessory) and posterior (=caudal)). When the bronchi enter the lung, they divide into a major segment (at a small angle from the parent airway) and a minor segment (at a much greater angle to the parent airway). This results in air moving at lower velocity entering the minor branch. This is called monopodal branching and is a feature of the rat and the mouse. A feature particular of rats is the presence of serous cells in the respiratory epithelium.

Lymphoid system

The spleen of the rat is elongated and slightly flattened, with rounded ends. A transverse section is a flattened isosceles triangle. Length varies from 3-5cm and width is about 1cm. Spleens from males are bigger than those of females. Splenic extramedullary haematopoiesis is not as marked as in the mice and prominent haematopoietic activity usually denotes disease.

Haemal lymphnodes, red and 1-3mm diameter are usually found near the splenic vessels and kidney and embedded superficially in the thymus. These have endothelium lined sinuses and there is marked accumulation of haemosiderin in these organs. Their function is unknown.

The thymus is in the precardial mediastinum, is bilobed and triangular and has a smooth ivory to pink surface. Thymic involution can occur as early as 1 year of age in males.

In the bone marrow, haematopoiesis continues in long bones throughout life.

Digestive system

Oral cavity: The dental formula of the rat is 2(I 1/1; M 3/3). Incisors are continuously erupting and are maintained at a constant length by attrition of occlusal surfaces. This results in total renewal every 40-50 days. Their yellow colour increases with age and is a result of iron containing pigments.

The major salivary glands are located along the ventral neck and extend upward to the base of the ear in close association with the mandibular lymph nodes and extraorbital lacrimal gland. There is sexual dimorphism in salivary glands: Male parotids and submandibular glands are twice the size of females’, with increased secretory granules in the cytoplasm of serous cells.

Oesophagus: The soft palate is long. As a result of this, the oesophageal opening, epiglottis and larynx are cranial to the nasopharyngeal opening.

Stomach: Composed by a proximal non-glandular squamous region (60%) and a glandular distal region (40%) delimited by a ridge.

Intestine: The small intestine measures from 107-122cm, and its length increases with age. The duodenum comprises the first 7-10cm. The caecum is a 3-5cm long curved conical sac and the colon and rectum are 15cm long (the first 2-5cm is proximal colon and the remainder descending colon and rectum). There are multilobulated sebaceous circumanal glands in the area between the anal sphincter and the anal canal.

Liver: The liver has four lobes (left, median, right and caudate). The median, right and caudate lobes are subdivided in two sublobes. The rat has no gall bladder and the bile is not concentrated. Hepatocyte polyploidy and binucleated cells is common and increases with age

Urogenital system

The males have a paired, subcutaneous sebaceous preputial gland lateral to the base of the penis and the females a sebaceous clitoral gland, at the base of the clitoris, 4mm cranial and ventral to the vagina. Adult female rats develop cyclic uterine non-pathological infiltrates of eosinophils.

Locomotor system

The growth plates (physes) are not totally resorbed in the rat, suggesting that some increase in bone length continues throughout life. However, any increase in length becomes negligible after approximately 12 months of age.

Integument

The rat has two types of hair follicle: (a) larger follicles containing longer, thicker hairs and (b) smaller follicles with shorter finer hairs. Several smaller follicles are arranged around a central large follicle. All follicles can contain one or more hair shafts. The epidermis at the opening of hair follicles is thickened (4-6 cells); these areas are known as Haarscheibe plaques. Tactile hairs are found around the muzzle and have follicles with prominent vascular sinusoids, nerve endings and abundant interspersed striated muscle fibres.

There are eccrine glands in the dermis of the digital pads.

Rats have six pairs of mammary glands (cervical, cranial thoracic, abdominal, cranial inguinal and caudal inguinal). The cervical pair extend anteriorly to the salivary glands and the caudal inguinal caudally to the perianal region.

Endocrine glands

In the pituitary area, the circle of Willis is incomplete and the sella turcica is shallow. For these reasons, an increase in size of the pituitary does not impinge on these structures, as happens in other species. Expanding pituitary tumours in the rat apply pressure directly to the floor of the third ventricle and often cause dilatation of the lateral ventricles.

The adrenal glands of females are bigger than those of males, primarily because of a greater abundance of cortical tissue. This may be related to estrogen levels, since adrenal weights increase during oestrus.

The size and structure of the thyroid gland are dependent on a number of factors, including age, sex, nutrition, the iodine content of the diet, environment, etc. These variations make it difficult to establish reliable average values for thyroid size and weight. Parathyroid glands are 1 to 2mm long and oval. They are up to two times larger in females. Accessory parathyroid tissue can occur in the thymus or dorsolateral to the oesophagus near the larynx.

Sensory organs

Ear: The rat lacks ceruminous (apocrine) glands in the external auditory canal and there is a compound gland composed of 3-4 triangular lobules (Zymbal’s gland). This structure is slightly rostroventral to the ear and medial to the temporal bone.

Other

As in mice, rats have prominent brown fat, as a subcutaneous pad over the shoulders, neck, axillae and peritoneal tissue. The fur of male albino rats tends to yellow with age.

Diseases

Congenital and genetic

Nutritional and Environmental

Degenerative and Aging

Infectious

Bacterial

Viral

Parasitic

Mycotic

Neoplasia

Pulmonary lesions of unknown aetiology

The rat in toxicopathology

Spontaneous lesions

Induced lesions

References

- ↑ Krinke, George J. (2000). "History, Strains and Models". The Laboratory Rat (Handbook of Experimental Animals). Bullock, G.R., Bunton, T. (Eds.). Academic Press. pp. 3–16.

- ↑ Zhou Q et al. (2003) "Generation of fertile cloned rats by regulating oocyte activation". Science, 302, pp. 1179

- ↑ Rat Genome Sequencing Project Consortium (2004) "Genome sequence of the Brown Norway rat yields insights into mammalian evolution". Nature. 428, pp. 493-521

- ↑ Percy, D.H. and Barthold, S.W. (2007). “Rat”, In: Pathology of laboratory rodents and rabbits. Percy, D.H. and Barthold, S.W. (Eds.). Blackwell Publishing. pp. 125-178

- ↑ Pathology of the Fischer Rat (1990). Boorman, G.A., Eustis, S.L., Elwell, M.R., Montgomery Jr., C.A., MacKenzie, W.F., (Eds.). Academic Press Inc.