Small Animal Dermatology Q&A 17

| This question was provided by Manson Publishing as part of the OVAL Project. See more small animal dermatological questions |

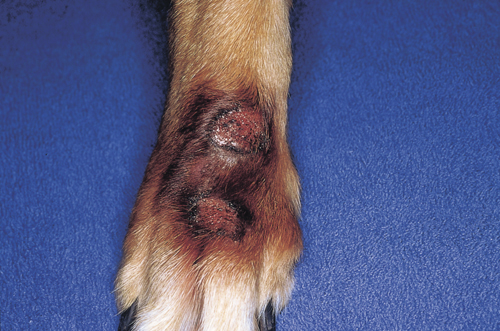

A 2-year-old dog was presented for evaluation of a mass on its forepaw. The lesion was raised, erythematous, moist, and firm to the touch. Closer examination revealed an erosive, circular lesion with a raised border; the lesion was slightly crater-like. A second healed lesion just distal to the first was also found, and extensive salivary staining was present on the paw. The owners reported the lesion had developed over the last several weeks, and this was the first occurrence of the lesion.

| Question | Answer | Article | |

| What is the clinical diagnosis? | Acral lick granuloma or dermatitis. |

Link to Article | |

|

What are the two major causes of this syndrome? |

The two major causes of this lesion are organic diseases and behavioral (obsessive–compulsive disorder). The latter is a diagnosis of exclusion, and this cannot be emphasized enough.

Assuming the skin scraping is negative, and while the fungal culture is pending, oral antibiotics, e.g. cephalexin (30 mg/kg PO q12h) would be the first choice therapy.

Radiographs of the region should be taken looking for evidence of an underlying cause, e.g. fracture, osteosarcoma. The dog should be carefully examined for evidence of joint disease. |

Link to Article | |

| What is a tail dock neuroma? | Tail dock neuroma is a rare complication of surgical tail docking. In this condition, the nerve endings regrow in a disorganized manner forming a neuroma. |

Link to Article | |