Difference between revisions of "Intussusception"

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

==Signalment== | ==Signalment== | ||

| − | |||

Intussusception occurs in dogs and cats, but gastroesophageal intussusception has only been reported in dogs. | Intussusception occurs in dogs and cats, but gastroesophageal intussusception has only been reported in dogs. | ||

| − | + | ||

German shepherd dogs and Siamese cats are over represented. German Shepherd dogs are particularly predisposed to gastroesophageal intussusception. | German shepherd dogs and Siamese cats are over represented. German Shepherd dogs are particularly predisposed to gastroesophageal intussusception. | ||

| − | + | ||

Young animals are most commonly affected, 80% of cases are less than a year old. | Young animals are most commonly affected, 80% of cases are less than a year old. | ||

| + | |||

==Diagnosis== | ==Diagnosis== | ||

Revision as of 21:13, 6 July 2010

| This article is still under construction. |

Description

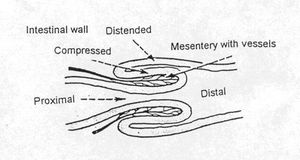

Intussusception is the invagination of one portion of the gastrointestinal tract into the lumen of the adjacent portion. The intussusceptum is the invaginated segment and the intussuscipien is the enveloping segment. A normograde intussusception is most common, but retrograde intussusception has also been reported.

Intussusceptions can be classified according to their location in the gastrointestinal tract. They usually occur in regions where there is a significant change in lumen diameter, such as ileocolic and gastroesphageal junctions. Ileocolic intussusceptions are most common, they frequently protrude from the rectum and must be distinguished from a rectal prolapse. In the case of an intussusception, it is possible to pass a probe next to the anus, but not in a rectal prolapse.

Depending on the site and severity, an intussusception results in a partial or complete obstruction to the gastrointestinal tract causing hypovolaemia, dehydration and shock. The condition is potentially serious and should be treated as an emergency.

Pathogenesis

Intussusception results from abnormal peristalsis. Vigorous contractions force the more proximal intestine to invaginate into the adjacent distal portion, taking its mesenteric attachment with it. Obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract causes distention which may lead to rupture and peritonitis. Compression of the mesenteric vessels cause vascular compromise to the instestine, resulting in venous congestion, oedema and if the aterial supply is damaged, full thickness necrosis. An inflammatory exudate is released from the serosal surface and fibrinous adhesions may form, making the structure irreducible.

Intussusception normally occurs due to gastrointestinal disease, although it is often hard to identify the cause. It is associated with any condition that increases peristalsis such as

- Enteritis

- Foreign body

- Heavy parasitism

- Previous intestinal surgery

- Intramural abscess/tumour

- Motility disorders.

- Change in diet

- Bacterial infection

Signalment

Intussusception occurs in dogs and cats, but gastroesophageal intussusception has only been reported in dogs.

German shepherd dogs and Siamese cats are over represented. German Shepherd dogs are particularly predisposed to gastroesophageal intussusception.

Young animals are most commonly affected, 80% of cases are less than a year old.

Diagnosis

Clinical Signs

Clinical signs vary depending on location, duration and the degree of obstruction and vascular compromise.

Acute Intussusception

- Vomiting

- Regurgitation

- Haematemesis

- Abdominal discomfort

- collapse

- Palpable abdominal tubular mass

- Diarrhoea- bloody and mucoid

- Tenesmus and Haematochezia in cases of ileocaecocolic intussusception

Chronic Intussusception

- Intermittent diarrhoea- bloody and mucoid

- Tenesmus

- Depression

- Anorexia

- Weight loss

Radiography

Plain abdominal radiographs do not always provide a definitive diagnosis. In cases of complete obstruction distented loops of intestine and a tubular soft tissue mass are usually obvious, but a partial obstruction will produce much more subtle signs which may be missed. A barium enema or upper gastrointestinal contrast study can be useful in identifying the site of obstruction but may result in delay of treatment and should be used cautiously as leakage of contrast into the abdominal cavity will result in peritonitis.

Ultrasound

Abdominal ultrasound will reveal a cylindrical mass with layering of the intestinal wall. The intestines may also be hypomotile, with distension proximal to the obstruction.

Endoscopy

Colonoscopy can identify ileocolic or caecocolic intussusception. Oesopgagoscopy can reveal a gastroesophageal intussusception, a soft tissue mass is visible in the lumen of the oesophagus.

Pathology

The degree of damage to the intestine depends on the severity of the intussusception. In severe or chronic cases fibrinous adhesions form between surfaces making the structure irreducible. Necrosis of the tissue usually follows.

Intussusception may occur due to post mortem change, in this case there are no other associated changes and the invaginated intestine is easily reducible.

Treatment

Fluid therapy and correction of electrolyte and acid-base abnormalities should be carried out prior to surgical correction.

Surgery is required to manually reduce the intussusception, it may be necessary to resect and anastomose the intestine in cases where the adhesions have formed. This decision depends on the viability of the intestines, as determined by the colour, vascular supply and presence or absence of peristalsis.It is important to preserve as much of the intestine as possible to avoid short bowel syndrome.

Complications include dehiscence at the site of anastomosis, peritonitis, recurrence (11-20%, most common within 1-5 days post surgery), ileus, intestinal obstruction and short bowel syndrome. Recurrence can be prevented by enteroplication of the small intestine, or by a left-sided gastroplexy of the fundus in cases of gastroesophageal intussusception.

Prognosis

This depends on the location, completeness and duration of the intusussception. The prognosis is good in animals treated with early surgical intervention and aggressive supportive care. The prognosis is poor for animals with perforated intestine and peritonitis.

References

- Barreau, P. (2008) Intussusception: Diagnosis and Treatment 33rd WSAVA Congress

- Ettinger, S.J. and Feldman, E. C. (2000) Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine Diseases of the Dog and Cat Volume 2 (Fifth Edition) W.B. Saunders Company.

- Fossum, T. W. et. al. (2007) Small Animal Surgery (Third Edition) Mosby Elsevier

- Hall, E.J, Simpson, J.W. and Williams, D.A. (2005) BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Gastroenterology (2nd Edition) BSAVA

- Nelson, R.W. and Couto, C.G. (2009) Small Animal Internal Medicine (Fourth Edition) Mosby Elsevier.

- Tilley, L.P. and Smith, F.W.K.(2004)The 5-minute Veterinary Consult(Third edition) Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.