Coagulation Tests

| This article is still under construction. |

Also known as: coagulation profile, clotting profile, clotting tests.

Introduction

Haemostasis

Normally, haemostastis is maintained by three key events. The first stage, primary haemostasis, involves platelets and the blood vessels themselves. It is triggered by injury to a vessel, and platelets become activated, adhere to endothelial connective tissue and aggregate with other platelets. A fragile plug is thus formed which helps to stem haemorrhage from the vessel. Substances are released from platelets during primary haemostasis. Vasoactive compounds give vasoconstriction, and other mediators cause continued platelet activation and aggregation, as well as contraction of the platelet plug. Primary haemostasis ceases once defects in the vessels are sealed and bleeding stops.

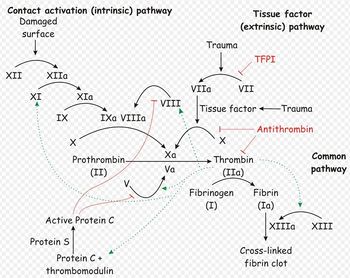

The platelet plug formed by primary haemostasis is fragile and must be reinforced in order to provide longer-term benefit. In secondary haemostasis, proteinaceous clotting factors interact in a cascade to produce fibrin to reinforce the clot. Two arms of the cascade are activated simultaneously to achieve coagulation: the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. The intrinsic pathway is activated by contact with collagen due to vessel injury and involves the clotting factors XII, XI, IX and VIII. The extrinsic pathway is triggered by tissue injury and is effected via factor VII. These pathways progress independently before converging at the common pathway, which involves the factors X, V, II and I and ultimately results in the formation of fibrin from fibrinogen. Factors I, VII, IX and X are dependent upon vitamin K to become active.

The end product of haemostasis is a solid clot of fused platelets enclosed in a mesh of fibrin strands. It is important that uncontrolled, widespread clot formation is prevented, and so a fibrinolytic system exists to breakdown fibrin within blood clots. The two most important anticoagulants involved in fibrinolysis are antithrombin III (ATIII) and Protein C. The end products of fibinolysis are fibrin degratation products (FDPs).

Disorders of Haemostasis

Abnormalities can develop in any of the components of haemostasis. Disorders of primary haemostasis include vessel defects (i.e. vasculitis), thrombocytopenia (due to decreased production or increased destruction) and abnormalities in platelet function (e.g. congenital defects, disseminated intravascular coagulation). These lead to the occurence of multiple minor bleeds and prolonged bleeding. For example, petechial or ecchymotic haemorrhages may be seen on the skin and mucous membranes, or ocular bleeds may arise. Generally, intact secondary haemostasis prevents major haemorrhage in disorders of primary haemostasis. When secondary haemostasis is abnormal, larger bleeds are frequently seen. Haemothroax, haemoperitoneum, or haemoarthrosis may occur, in addition to subcutaneous and intramuscular haemorrhages. Petechiae and ecchymoses are not usually apparent, as intact primary haemostasis prevents minor capillary bleeding. Examples of secondary haemostatic disorders include clotting factor deficiencies (e.g. hepatic failure, vitamin K deficiency, hereditary disorders) and circulation of substances inhibitory to coagulation (FDPs in disseminated intravascular coagulation, lupus anticoagulant). If fibrinolysis is defective, thrombus formation and infarctions may result. Thrombus formation may be promoted by vascular damage, circulatory stasis or changes in anticoagulants or procoagulants. For example, ATIII may be decreased. This can occur by loss due to glomerular disease or accelarated consumption in disseminated intravascular coagulation or sepsis.

It is therefore important that all aspects of haemostasis can be evaluated. This will help to identify the phase affected and to pinpoint what the abnormality is. There are tests available to assess primary haemostasis, secondary haemostasis and fibrinolysis.

Tests Evaluating Primary Haemostasis

Primary haemostasis is dependent on the activity of platelets and, to a lesser extent, the blood vessels themselves. Platelets are the smallest solid formed component of blood, and are non-nucleated, flattened disc-shaped structures1. Their activity leads to vascoconstriction and the formation of platelet plugs to occlude vessel defects. Platelets develop in the bone marrow, and have a life span of around 7.5 days. Around two thirds of platelets are found in the circulation at any one time, with the remainder residing in the spleen1.

Apart from unusual cases involving vasculitis, there are two causes of defects in primary haemostasis: thrombocytopenia (reduced platelet number), or thrombocytopathia (defective platelet function)2.

Platelet Number

A platelet count can give valuable information in all critically ill animals and is an essential laboratory tests for patients with bleeding concerns. Platelet numbers may be rapidly estimated by examination of a stained blood smear, of quantified by manual or automated counting techniques. To estimate the platlet number using a blood smear, the slide should first be scanned for evidence of clumping that would artificially reduce the count. The average number of platelets in ten oil-immersion fields should be counted, and a mean calculated. Each platelet in a high-power field represents 15,000 platelets per microlitre2. A "normal" platelet count therefore gives aroung 10-15 platelets per oil-immersion field.

The reference range given for platelet number is usually around 200-500x109 per litre, although this varies depending on the laboratory used. Clinical signs due to thrombocytopenia are not commonly encountered until the platelet count drops below 50X109/l, when increased bleeding times may be seen. Haemorrhage during surgery becomes a concern with counts lower than 20X109/l, and spotaneous bleeding arises when platelets are fewer than 5X109/l2. These cut-offs are lowered if platelet function is concurrently affected, for example by the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs1.

Buccal Mucosal Bleeding Time

The buccal mucosal bleeding time is a simple test that gives a rapid assessment of platelet function, providing platelet numbers are normal. If platelet numbers are below 50x109l, this test should not be performed since bleeding may not be as easily stopped.

The buccal mucosal bleeding time (BMBT) is one of the only clinically available methods of measuring platelet function. It is performed by use of a standardized bleeding device to make an incision in the buccal mucosa of the upper lip. The duration of time between making the incision and the cessation of bleeding is measured. The upper lip is kept turned up (usually by a gauze muzzle) through out the procedure and blood is gently absorbed away from the incision without disturbing the clot. A normal BMBT is considered to be approximately 3 minutes and greater than 5 minutes is considered prolonged. Abnormalities in platelet function and significant thrombocytopenia (<50,000/microL) will cause prolongations in the BMBT. Causes of thrombocytopathia include uremia, non-steroidal drug therapy such as aspirin and von Willebrands disease. Unfortunately the BMBT is a fairly crude test of platelet function and it has been found to be normal in some patients with a known platelet function disorder and abnormal in patients with normal platelet function. As such the results of this test should be interpreted with some caution.

When a small slit is made in the skin, the hemostatic mechanisms necessary for coagulation are activated. Without the aid of external pressure, bleeding usually stops within 7 to 9 minutes. Technique

The test is performed using a disposable template that produces a uniform incision. The incision, either horizontal or vertical, is placed on the lateral aspect of the forearm, about 5 cm below the antecubital fossa, after a blood pressure cuff has been inflated to approximately 40 mm Hg. Blood may be absorbed off the skin, but care must be taken to avoid pressure. The time is measured from the moment of incision to the moment bleeding stops. The time may vary based on the commercial template used, the direction of the incision, and the location on the arm. Each institution must establish its own upper limits of normal. Basic Science

The vascular platelet phase of hemostasis consists of a primary vasoconstriction that serves to decrease blood flow, followed by adherence of platelets to the ruptured endothelium (adhesion) and each other (aggregation). This platelet aggregate, called the platelet plug, stops the bleeding and forms a matrix for the clot. The bleeding time is an excellent screening test for the vascular platelet phase of hemostasis. It depends on an intact vasospastic response in a small vessel and an adequate number of functionally active platelets. Clinical Significance

Patients with abnormalities of the vascular platelet phase of hemostasis present with purpura (petechiae and ecchymoses) and spontaneous bruising. They may have mucosal bleeding and fundus hemorrhages. Commonly, the problem is either thrombocytopenia, easily evaluated by a platelet count, or abnormal platelet function, which can be diagnosed with platelet function studies. The most common acquired platelet function abnormalities are drug induced (aspirin and the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents) and uremia. The most common hereditary abnormality is von Willebrand's disease.

Tests Evaluating Secondary Haemostasis

Secondary hemostasis describes the formation of a cross linked fibrin meshwork in the blood clot and is dependent on the soluble coagulation factors. Abnormalities in secondary coagulation can occur from insufficient coagulation factors or the presence of inactive coagulation factors. The soluble coagulation factors are traditionally divided into the intrinsic, extrinsic and common pathways, as described in the introduction.

ACT

2:The activated clotting time (ACT) can be performed manually with the specific blood tubes containing diatomaceous earth (ACT tubes, Becton Dickinson) or with an automated analyzer. If performed manually the tubes must be kept at body temperature through out the procedure, this is ideally achieved by the use of a controlled warm water bath or they can be kept under an arm and gently rocked. 2ml of blood are added to the tube and the time from collection to clot formation is measured. The normal ACT in a dog is 90-120 seconds and < 75 seconds in cats. The ACT evaluates both the intrinsic and common coagulation pathways so it is prolonged with abnormalities or deficiencies in factors XII, XI, IX, VIII, X, V, II or I. Because the ACT is a test on whole blood it can also be mildly prolonged by thrombocytopenia (<50,000). Disease processes expected to prolong the ACT include DIC, liver disease, Vitamin K antagonist poisons and hemophilia A & B.

PT

2:The prothrombin time (PT) is measured by an automated analyzer and there are some new point of care machines now available that allow this and APTT to be measured on an emergency basis. The prothrombin time is a measure of the extrinsic and common coagulation pathways. It will be prolonged by deficiency or abnormalities in coagulation factors VII, X, II or I. Disease processes expected to prolong the PT include Vitamin K antagonists, liver disease and DIC.

(A)PTT

Definition

The aPTT measures the time necessary to generate fibrin from initiation of the intrinsic pathway (Figure 157.1). Activation of factor XII is accomplished with an external agent (e.g., kaolin) capable of activating factor XII without activating factor VII. Since platelet factors are necessary for the cascade to function normally, the test is performed in the presence of a phospholipid emulsion that takes the place of these factors. The classic partial thromboplastin time depends on contact with a glass tube for activation. Since this is considered a difficult variable to control, the "activated" test uses an external source of activation. Technique

Citrated plasma, an activating agent, and phospholipid are added together and incubated at 37°C. Calcium is added, and the time necessary for the clumping of kaolin is measured. The normal time is usually reported as less than 30 to 35 seconds depending on the technique used. In fact, there is a normal range of about 10 seconds (e.g., 25 to 35), and decreased values ("short") may also be abnormal. Basic Science

This test is abnormal in the presence of reduced quantities of factors XII, IX, XI, VIII, X, V, prothrombin, and fibrinogen (all integral parts of the "intrinsic" and "common" pathway. It is usually prolonged if a patient has less than approximately 30% normal activity. It can also be abnormal in the presence of a circulating inhibitor to any of the intrinsic pathway factors. The differentiation of inhibitors from factor depletion is important and can best be accomplished by a mixing study in which patient and normal plasma are combined in a 1:1 ratio and the test is repeated on the mixed sample. If the abnormal value is corrected completely, the problem is factor deficiency. If the result does not change or the abnormality is corrected only partially, an inhibitor is present. This difference stems from the above mentioned fact that the aPTT will be normal in the presence of 50% normal activity. Clinical Significance

The aPTT is a good screening test for inherited or acquired factor deficiencies. Inherited disorders including classic hemophilia A (factor VIII deficiency) and hemophilia B (factor IX deficiency, or Christmas disease) are well-known diseases in which the aPTT is prolonged. Other intrinsic and common pathway factors may also be congenitally absent. These conditions are rare but have been described for all factors. A number of kindreds with abnormalities of factor XII activation have been described. They are usually associated with a prolonged aPTT without clinical signs of bleeding. Acquired factor deficiency is common. Vitamin K deficiency, liver dysfunction, and iatrogenic anticoagulation with warfarin are most common. Factor depletion may also occur in the setting of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), prolonged bleeding, and massive transfusion.

A prolonged aPTT that cannot be completely normalized with the addition of normal plasma can be explained only by the presence of a circulating inhibitor of coagulation. The presence of these inhibitors is almost always acquired, and their exact nature is not always apparent. From a clinical point of view, the most common inhibitors should be considered antithrombins. These compounds inhibit the activity of thrombin on the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin (Figure 157.1). The two most common inhibitors are heparin, which acts through the naturally occurring protein antithrombin III (AT III), and fibrin degradation products (FDP), formed by the action of plasmin on the fibrin clot and usually present in elevated concentrations in DIC and primary fibrinolysis.

Other inhibitors appear to be antibodies. The easiest to understand is the antibody against factor VIII in patients with hemophilia A treated with factor VIII concentrate. Inhibitors against other factors have been described with a variety of diseases that follow a variable course. When characterized, they have been immunoglobulins.

A particular problem may be seen in patients suffering from systemic lupus erythematosus. These patients may present with a prolonged aPTT without evidence of bleeding. Some present with thrombosis. The abnormality cannot be corrected with normal plasma and has been referred to as the "lupus anticoagulant." This phenomenon does not represent an in vivo problem with the coagulation cascade. Rather, it is a laboratory abnormality caused by the presence of a serum constituent that interferes with the in vitro partial thromboplastin test.

Occasionally the reported value of the aPTT will be lower than normal. This "shortened" time may reflect the presence of increased levels of activated factors in context of a "hypercoagulable state." It is seen in some patients in the early stages of DIC but should not be considered diagnostic for that entity.

PIVKA

Tests Evaluating Fibrinolysis

Fibrin Degradation Products

References

- Fischbach, F T and Dunning, M B (2008) A manual of laboratory and diagnostic tests, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

- Hopper, K (2005) Interpreting coagulation tests. Proceedings of the 56th conference of La Società culturale italiana veterinari per animali da compagnia.

- Howard, M R and (2008) Haematology: an illustrated colour text, Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Walker, K H et al (1990) Clinical Methods: The history, Physical and Laboratory Examinations (Third Edition), Butterworths.