Introduction

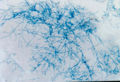

Apergillosis is a disease of the respiratory system caused by several Aspergillus spp.. Aspergillus fumigatus is the most frequently encountered species in domestic animals but Aspergillus tereus has also been reported. Aspergillus is a ubiquitous saprophyte and is found worldwide. It is also a component of normal hair, skin and mucosal flora in both humans and animals. Commonly affected species include birds, dogs, cats, horses and cattle but the disease has been reported in many other wild and domestic species.

Pathogenesis

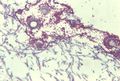

In dogs, spores are inhaled from the environment leading to fungal colonisation of the nasal cavities. Following their deposition in tissue and recognition by phagocytes, an inflammatory response is triggered. Haemolytic and dermonecrotic toxins as well as fungal protease and elastase are released leading to tissue damage.

In horses, the pathogenesis of guttural pouch mycosis is largely unknown but is thought to relate to damage to the mucosal layer of the pouches by trauma or infection. This enables opportunistic Aspergillus fungi to invade and colonise the damaged tissue.

Clinical signs and features

Dogs

Aspergillosis is a common cause of nasal disease in dogs. Cases occur most commonly in young to middle aged male dogs, but there is no apparent age or sex predilection. A higher prevalence of disease has been reported in doliocephalic breeds and outdoor/farm dogs. Clinical signs are those seen with any chronic nasal disease and include sneezing, unilateral or bilateral serosanguinous nasal discharge, ulceration of the nares, nasal pain and epistaxis. Neurological signs may be displayed if there is involvement of the cribriform plate.

The disease is usually localised to the paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity but a disseminated form with granulomas and infarcts has been reported, particularly in German Shepherds. This form of disease often involves multiple organ systems including the spleen and kidneys. Clinical signs include lethargy, anorexia, urinary incontinence and haematuria. The vertebrae are frequently affected and osteomyelitis and discospondlylitis are common features. Dermatological signs of disseminated aspergillosis include abscesses, draining tracts, oral ulcers and cutaneous nodules.

Horses

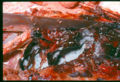

In the horse, Aspergillus most commonly affects the guttural pouches but infection may also lead to abortion, keratomycosis and rarely pulmonary aspergillosis. There is no age, sex or breed predisposition for guttural pouch mycosis and both left and right pouches are affected with equal frequency. Guttural pouch mycosis is characterised by spontaneous epistaxis (often in a resting horse) as a result of fungal erosion of the internal carotid artery. Other clinical signs include nasal discharge and dysphagia. Mycotic plaques are usually located on the caudodorsal aspect of the medial guttural pouch.

Cattle

Aspergillosis has a number of clinical manifestations in the cow including mastitis, placentitis, diarrhoea, ocular infection and mycotic pneumonia. Abortion in the second or third trimester of pregnancy has also been described. In the case of pulmonic disease, clinical signs may include pyrexia, cough, dyspnoea and tachypnoea but may be limited to vague signs such as weight loss or signs of mild respiratory disease. In aborting cattle, the foetus and placenta are retained and foetal lesions such as bronchopneumonia and dermatitis may be seen. Mastitic cows may display depression, weight loss and pyrexia with purulent mammary secretions and a hot, swollen udder.

Birds

Three forms of the disease have been reported in avian species; a diffuse infection of the air sacs; a diffuse pneumonic form and a nodular form involving the lungs. In chicks and poults the disease is known as 'brooder pneumonia' and may affect many birds in a flock. Animals become infected due to inhalation of spores from contaminated feed or litter. Clinical signs include dyspnoea, diarrhoea, listlessness, pyrexia, loss of appetite and loss of condition. Seizures and torticollis may occasionally occur if infection disseminates to the brain.

Diagnosis

Dogs

Radiology is often performed in the diagnostic work up of an animal with suspected Aspergillosis. It should always be performed prior to other procedures such as rhinoscopy and biopsy in order to prevent haemorrhage that may obscure subtle radiographic findings. Open-mouth ventro-dorsal views often reveal generalised radiolucency and lysis of the turbinate bones. Additionally, cytological examination of aspirates often reveals presence of fungal hyphae with granulomatous to suppurative inflammation and necrosis. Rhinoscopy may also be used to directly visualise the lesions, revealing characteristic white-green fungal plaques and destruction of the nasal turbinates. It also allows collection of material for fungal culture. This may be achieved using Sabouraud's dextrose agar in order to demonstrate the organism but should not be used as the sole means of diagnosis due to the ubiquitous nature of Aspergillus in the environment. White colonies form initially which turn dark green, flat and velvet-like in appearance. Serological findings such as immunoelectophoresis, ELISA and agar gel diffusion may provide additional diagnostic information.

Horses

Diagnosis is obtained following endoscopic examination of the guttural pouches and observation of white-yellow-black mycotic plaques on the mucosal surface of the guttural pouches. Care must be taken whilst performing endoscopy due to the risk of dislodgement of a thrombus on the affected artery.

Treatment

Dogs

The treatment of choice is topical application of the anti-fungal agent Clotrimazole. It is administered for one hour under general anaesthetic via indwelling catheters placed in the frontal sinus. Several treatments may be required. For cases that are non-responsive to Clotrimazole, treatment with Enilconazole may be attempted but this is associated with a higher complication rate.

Horses

Trans-arterial coil embolisation under fluoroscopic guidance is performed in order to cause internal occlusion of the affected arteries. Following arterial occlusion the mycotic plaques usually resolve without necessitating further treatment.

Cattle

Antifungal agents are currently unlicensed and management of the disease usually relies on preventative measures such as ensuring clean bedding and good husbandry.

Test yourself with the Systemic Mycoses Flashcards

Literature Search

Use these links to find recent scientific publications via CAB Abstracts (log in required unless accessing from a subscribing organisation).

Aspergillosis in dogs publications

Aspergillosis in cats publications

Aspergillosis in horses publications

Aspergillosis in cattle publications

Aspergillosis in birds publications

Aspergillosis in sheep publications

Aspergillosis in goats publications

Aspergillosis in pigs publications

References

- Barr, S. C., Bowman, D. D. (2006) The 5-minute Veterinary Consult Clinical Companion: canine and feline infectious diseases and parasitology Wiley-Blackwell

- Carter, G. R., Wise, D. J. (2004) Essentials of Veterinary Bacteriology and Mycology Wiley-Blackwell

- Ettinger, S. J. (2000) Pocket Companion to Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine Elsevier Health Sciences

- Muller, G. H., Scott, D. W., Kirk, R. W., Miller, W. H., Griffin, C. E. (2001) Muller and Kirk's Small Animal Dermatology Elsevier Health Sciences

| This article has been peer reviewed but is awaiting expert review. If you would like to help with this, please see more information about expert reviewing. |