Tuberculosis - Cattle

Description

Tuberculosis in cattle is caused by Mycobacterium bovis. It is a chronic disease characterised by granulomatous nodular lesions in any organ, although the respiratory system is most commonly affected. The nodules often become necrotic with a caseous centre. The primary lesions may disseminate to involve other body systems.

A higher level of infection is required to establish the alimentary form of the disease and this is reflected by its lower incidence in comparison to the respiratory form.

Inhalation of ruminal gases is the most common route of entry for the mycobacterium organism, and spread of the disease is usually via cow-to-cow contact. Cattle can also become infected by ingestion of the causative agent; this is the usual route of entry when the badger is involved, by infecting grazing land or water troughs. Calves with infected dams can become affected via the milk, and intrauterine infection at coitus has been reported.

Historically bovine TB was a major cause of human TB, but the introduction of tuberculin testing and slaughter, meat inspection at abattoirs, the pasteurisation of milk and the BCG vaccination has dramatically reduced transmission to humans and bovine TB as a cause of human disease is now very low indeed.

The disease is of serious economic importance to farmers because of the stringent control measures, which remain in place. These include the slaughter of infected animals and movement restrictions placed on farms with reactors or inconclusive results.

Signalment

The disease usually affects heifers or young stock but cases can occur in cattle of any age. TB is more common in dairy herds.

Incidence of the disease has increased over the past 15 years; it is prevalent in Wales and the southwest of England but is re-emerging in other parts of the UK such as the west Midlands and northwest England.

Most warm-blooded animals are susceptible to bovine TB and can act as a reservoir for infection. The disease in cattle has been associated with wildlife species in a number of countries; the European badger and red deer in the UK, opossums and ferrets in New Zealand, mule deer, white-tailed deer, elk, and bison in North America and water buffalo in Australia.

Diagnosis

The intradermal comparative tuberculin test is widely used in the UK for diagnosis of the disease. Two injections are given subcutaneously in the neck of cattle, one is avian and the second bovine tuberculin purified protein derivative (PPD. The thickness of the skin is recorded at each injection site. The test is read after 72 hours, and the thickness of the skin is remeasured. Interpretation is based on finding a swelling or increase in skin thinkness at the site of the injection. A comparison must be made between the reaction to avian and the bovine tuberculin to account for cross reactivity with related diseases, such as atypical mycobacteriosis, or Johne's disease.

A single intradermal test is used in many countries but has the disadvantage of giving reactors to avian tuberculosis and Johne's disease.

Clinical Signs

Location and severity depend on which body systems are affected and the advancement of the disease. Due to the testing and slaughter policy most cases in the UK are identified before development of clinical signs.

Respiratory form

- Chronic cough- soft and productive

- Tachypnoea

- Dyspnoea

- Dull areas on auscultation of the lungs in advanced cases

Alimentary form

- Few clinical signs

- Diarrhoea

- Bloat

Mammary involvement is now rarely seen; the uterine form is also uncommon but may result in abortion.

Laboratory Tests

An ELISA test has been developed but is not widely used. The gamma interferon test can also be used for diagnosis of the condition.

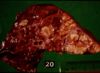

Pathology

Findings at post mortem depend on the route of entry of the organism, whether it became generalised or not and the stage of the disease. One or more lymph nodes will display the characteristic granulomatous tubercles. In the respiratory form the mediastinal and bronchial lymph nodes are affected, with lesions in the lungs.

If the mycobacteria disseminated from the primary complex then lymph nodes in other regions will also be affected and there will be multiple small foci of infection on other organs.

Microscopically there are epithelioid cells, with large vesicular nuclei and pale cytoplasm and giant cells, formed by the fusion of macrophages, are found at the centre of tubercles. Surrounding this there is a narrow layer of lymphocytes, mononuclear cells and plasma cells, more advanced cases show peripheral fibroplasia andcentral necrosis.

Treatment

Treatment is not usually an option due to the chronic nature of the disease, zoonotic potential and test and slaughter policy.

Control in many countries is centred on tuberculin testing with slaughter of reactors and movement restrictions to the premises. Research work continues into the use of vaccination, or a cull strategy for the associated wildlife populations.

Prognosis

Poor.

References

- Andrews, A.H, Blowey, R.W, Boyd, H and Eddy, R.G. (2004) Bovine Medicine (Second edition), Blackwell Publishing