Behavioural Consultation and History Taking

Introduction

The majority of behavioural cases presented in veterinary practice are related to normal feline behaviour. However, it is essential to consider that some alterations in behaviour can also be concomitant with the simultaneous presence of clinical disease. In cats specifically, links between lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) and soiling indoors stress the necessity for a full physical and clinical examination before any type of behavioural therapy is implemented. It is also crucial to remember that pathologies may cause continuing behavioural problems even when the illness has been clinically resolved.

Other examples of conditions which can cause alterations in feline behaviour include:

- Diabetes mellitus: cats initially presented for a lapse in house training

- Hyperthyroidism: aggression to both or either other cats or owners

As well as behavioural expressions of physical disease, behavioural symptoms can result as a outcome of shifts in neurochemical equilibriums in the CNS. Additionally, high levels of stress can cause alterations in behavioural, physiologic and immune responses. Alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary axis have been linked to stress as well as effects on levels of dopamine, serotonin, noradrenaline and prolactin. In animals, stress is a contributing factor to gastrointestinal disturbances, skin conditions, feline interstitial cystitis as well as compulsive disorders and increased fear responses.

History Taking

As with other areas of veterinary practice, a thorough history is paramount. In a behavioural context history taking must be especially thorough and can be a very long process. Initially, it must be determined what the issue is from the client’s perspective and what they are expecting as a solution. It is important to collect information about the cat’s environment and not centre solely on the presenting behaviour. The history should also cover the medical background of the cat, the upbringing of the animal, current lifestyle and information about the specific problem which is of concern.

Key points in a behavioural history should cover:

- Clinical history

- Any current drugs being administered

- Any former behavioural therapy as well as corrective measures being implemented and their effectiveness.

- The animal’s disposition

- Breeding and early upbringing

- Current lifestyle - environment and housing

- Relationship between pet and owner

- The rate of occurrence of problem behaviour and its predictability

- A thorough description of the issue, along with information about time and age of onset, duration of episodes, frequency and development including any alterations in pattern.

- The owners response to the issue

Considering what happens before and after the problem behaviour is also important as this can often provide a clue to the stimulus. In addition videos or visits to the animals normal environment may be useful.

Social Structure within the Home

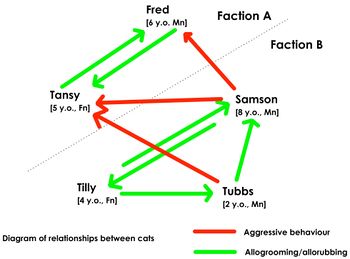

If more than one cat reside within the same home, it is important to establish their relationship. An interactive diagram is ideal, similar to the one in the image. Record the friendly and aggressive behaviours between individuals:

- Friendly: e.g. grooming, rubbing against, tail-up greeting

- Aggressive: e.g. chasing, growling, hissing, spitting, fighting

It is possible to have no affiliative behaviour at all between a whole group of cats, or a to find that there is a single outsider. Factions often require their own resources so that they can coexist without competition.

House Layout

Draw a diagram of the house to show where the cats have food, water, litter trays and cat flap. Also mark on this where urine or faeces have been found and which cat left them, if relevant. This is particularly important in cases of housesoiling but is useful in other cases too as it helps to establish the appropriate allocation of resources.

References

- Heath, S. Chapter 5, Common Feline Behavioural Problems – Feline Medicine and Therapeutics.

- Merck Veterinary Manual (10th Edition) - Behaviour

| This article is still under construction. |