Key-Gaskell Syndrome

Also known as: Autonomic Polyganglioneuropathy — Feline Dysautonomia

Introduction

Key-Gaskell Syndrome refers to the clinical signs observed in cats with abnormal function of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. It is similar to grass sickness in horses and, like this disease, it is often fatal.

The syndrome has occurred as outbreaks[1] in the past in the UK, continental Europe and occasionally in the USA. It was first described by Key and Gaskell as a 'puzzling syndrome' causing pupillary dilatation in cats at the start of a major outbreak in the UK in 1982[2]. It is currently described only sporadically but recent reports suggest that the incidence of the disease may be increasing again.

The cause of the dysautonomia is not known but numerous factors have been implicated and it is generally thought to occur after exposure to a toxin, possibly in dry food or vaccines [?reference]. As with grass sickness, it has also been suggested that toxins produced by Clostridium botulinum may be involved in the pathogenesis of the disease and a recent study showed that cats with the disease developed significantly higher titres of IgA antibody to botulinum toxins C and D than healthy controls[3]. Whatever the cause, degenerative lesions develop in the autonomic ganglia, intermedio-lateral columns of spinal grey matter and in the axons of the sympathetic neurones.

Signalment

Historically, Key-Gaskell syndrome was reported most frequently in cats but the disease has now been shown to occur in dogs[4][5][6], particularly younger animals. There is no apparent sex predisposition but the Labrador Retriever breed may be predisposed to the development of dysautonomia.

In a recent study of 65 dogs confirmed as having dysautonomia, those raised and housed in rural environments appeared to be at greater risk (56/65 dogs) for dysautonomia than dogs from urban environments[7].

Diagnosis

Clinical Signs

The sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems are involved in the regulation of multiple organ systems, particularly the gastro-intestinal tract and the secretory glands. Common clinical signs therefore include:

- Anorexia and constipation due to intestinal ileus.

- Abdominal distension may occur as a result of generalised paralytic ileus.

- Megaoesophagus due to failure of oesophageal motility. This may cause regurgitation and secondary aspiration pneumonia.

- Depression

- Bradycardia

- Decreased lacrimation and salivation due to reduced tone in the parasympathetic nerves that stimulate secretion. The xerostomia caused by reduced production of saliva may be apparent as dry mucous membranes on clinical examination.

- Pupillary dilatation due to reduced tone of the constrictor muscle of the iris, usually controlled by the parasympathetic fibres of the short ciliary nerves.

The most frequent clinical signs associated with the syndrome are depression, anorexia, constipation and regurgitation or vomiting. Incontinence (faecal and urinary) has been observed less frequently.

Diagnostic Imaging

Oesophageal dilatation may be observed on plain radiographs of the chest. A 'trachea stripe sign' may also be visible due to the compression of the tissue between the oesophagus and trachea.

Oesophageal hypomotility may be evident with barium contrast study or using fluoroscopy to observe the dynamic passage of food boluses into the stomach.

Pharmalogical Tests

Various provocative tests can be used to assess the autonomic nervous systems of animals with suspected Key-Gaskell syndrome:

- Topical ocular administration of dilute pilocarpine should result in miosis, which implies a positive result. However, not all animals respond and the response is dependent on the degree of damage to the postganglionic parasympathetic neuron causing (denervation) supersensitivity of the iris muscle.

- Intra-venous or subcutaneous administration of atropine (a parasympatholytic) should result in an increase in the heart rate. A failure to respond implies a positive result.

- Intra-dermal administration of histamine should result in a classical wheal and flare response but this may be dampened in those animals with dysautonomia. An absence of the wheal and flare response is therefore a positive result.

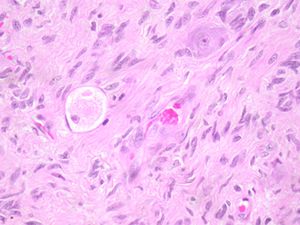

Pathology

- Histologically there is marked reduction in the number of neurones in all autonomic ganglia in the ventral horn of all levels of spinal cord accompanied by proliferation of non-neuronal cells. Similar changes are found in the brainstem nuclei of the cranial nerves and features of chromatolytic degeneration may be apparent in the ganglia, spinal cord and sympathetic axons.

Differential Diagnosis

There are few differential diagnoses for this clinical presentation but, early in the course of disease, other causes of megaoesophagus should be considered.

Treatment

Treatment may be attempted with parasympathomimteic drugs but is largely supportive.

Supportive

Food should be provided from an elevated bowl or via a gastrostomy tube which can be left in place for several weeks if necessary. Total parenteral nutrition may be considered but this cannot be used as a long term option for nutrition and it is associated with many adverse effects.

Parasympathomimetic Drugs

Some dogs may show minor improvement on initiation of therapy with bethanechol or metoclopramide.

Prognosis

The prognosis is guarded or poor. Recovery rates in the cat are reported as 20-40% but it may take 2-12 months for the patient to recover fully. In the dog, recovery rates are lower. Even after making an apparent recovery, many animals are left with residual neurological deficits including intermittent regurgitation.

| Key-Gaskell Syndrome Learning Resources | |

|---|---|

To reach the Vetstream content, please select |

Canis, Felis, Lapis or Equis |

Search for recent publications via CAB Abstract (CABI log in required) |

Key-Gaskell Syndrome in cats and dogs publications |

References

- ↑ Cave TA, Knottenbelt C, Mellor DJ, Nunn F, Nart P, Reid SW Outbreak of dysautonomia (Key-Gaskell syndrome) in a closed colony of pet cats. Vet Rec. 2003 Sep 27;153(13):387-92.

- ↑ Key TJ, Gaskell CJ. Puzzling syndrome in cats associated with pupillary dilatation. Vet Rec. 1982 Feb 13;110(7):160.

- ↑ Nunn F, Cave TA, Knottenbelt C, Poxton IR. Association between Key-Gaskell syndrome and infection by Clostridium botulinum type C/D. Vet Rec. 2004 Jul 24;155(4):111-5.

- ↑ Schulze C, Schanen H, Pohlenz J. Canine dysautonomia resembling the Key-Gaskell syndrome in Germany. Vet Rec. 1997 Nov 8;141(19):496-7

- ↑ Wise LA, Lappin MR. A syndrome resembling feline dysautonomia (Key-Gaskell syndrome) in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1991 Jun 15;198(12):2103-6.

- ↑ Rochlitz I, Bennett AM. Key-Gaskell syndrome in a bitch. Vet Rec. 1983 Jun 25;112(26):614-5.

- ↑ Harkin KR, Andrews GA, Nietfeld JC. Dysautonomia in dogs: 65 cases (1993-2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002 Mar 1;220(5):633-9.

- Hall J.H, Wimpson J. W. and Williams D.A, (2005), Disorders of the Pharynx and Oesophagus, in BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Gastroenterology, 2nd Edition, British Small Animal Association, Gloucester, pp 142-143

- Harkin K.R, Andrews G.A, Nietfeld J.C, (2002), Dysautonomia in dogs: 65 cases (1993–2000) J Am Vet Med Assoc, Mar 1, 220(5): pp. 633-9

| This article has been peer reviewed but is awaiting expert review. If you would like to help with this, please see more information about expert reviewing. |

Webinars

Failed to load RSS feed from https://www.thewebinarvet.com/neurology/webinars/feed: Error parsing XML for RSS