Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy

Also known as: BSE — Mad Cow Disease

Introduction

BSE was first recognised in the United Kingdom in 1986 after a huge epidemic in the UK involving over 100,000 diseased cattle. With the exception of France and Portugal, the number of infected animals in other countries has remained low. The disease is now worldwide and has occurred in Europe, Asia, Middle East and North America.

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) is a progressive, fatal and non-febrile neurological disorder affecting adult cattle. BSE belongs to a group of diseases called transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE), also referred to as prion diseases. It can be caused by an infectious or genetic disorder. It occurs when a natural prion PrP changes in conformation into the pathogenic isoform PrPsc and causes the spongy degeneration of the brain. In genetic prion diseases, this may be caused by a somatic mutation in the PrPc gene or in infectious BSE, exposure to foreign PrPsc may start this conformation change, leading to a progressive cascade of conformational change of natural PrPc into PrPsc [1].

Cattle became exposed to the abnormal prions through the feeding of ruminant-derived protein within feedstuffs such as meat-and-bone meal (MBM). It is thought that changes in the rendering process of the MBM increased the survival of scrapie-like materials (prions) from infected sheep carcasses and the recycling of infected bovine materials lead to the spread of BSE through infected MBM.

There is no evidence to support the horizontal transmission of BSE under natural circumstances but there is evidence supporting vertical transmission [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]. BSE is notifiable and unlike scrapie is considered a zoonosis.

Signalment

The disease has a very long incubation period (average 4 – 5 years ) and mainly affects animals aged 4-6 years old. It causes progressive neurological signs which can last several months and results in mortality. There is no breed or sex predilection, however the incidence of BSE in dairy cows is much greater than beef cows, possibly correlated to the greater use of concentrate rations containing MBM.

Spongiform encephalopathies also occurred in new species such as the greater kudu, nyala, Arabian onynx, Scimitar horned oryx, eland, gemsbok, bison, ankole, tiger, cheetah, ocelot, puma, and domestic cats, during the 1990s [7], [8] , [1] and in 2005 a goat was confirmed positive for BSE in France. To date there is no scientific evidence that experimental oral BSE challenge of pigs and poultry with brain material from cattle with BSE results in disease.

Clinical Signs

The first sign is usually separation from the herd and reluctance to move into the milking parlour and the cows may respond by with vigorous kicking.

BSE-affected cattle show progressive neurological and behavioural changes, abnormalities of posture and movement, recumbency, changes in sensation and temperament and increased aggression. Nervousness, tremors, falling, hyperaesthesia to sound and touch and progressive weakness and hind-limb ataxia and agalactia or decreased milk yield are the most prominent clinical signs.

Other clinical signs include anorexia, weight loss, bruxism, ptyalism, trismus, pruritus, dull rough coat and ophthalmic signs including blindness, lacrimation, ptosis and prolapsed third eyelid.

Diagnosis

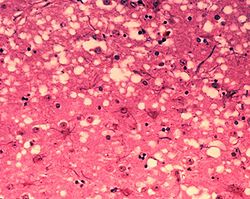

A preliminary diagnosis can be made on observation of the above clinical signs. The disease is characterized by accumulation of prion protein in the medulla oblongata (obex) region of the brain, as well as other tissues (lymph nodes, spleen, tonsils, etc) and can be confirmed on post mortem by the presence of the following histological changes in the brain: bilateral symmetrical vacuolation and immunohistochemical demonstration of the accumulation of the disease specific PrPsc in the grey matter of the brain, gliosis, hypertrophy of astrocytes, neuronal degeneration and cerebral amyloidosis.

The absence of detectable immune responses in BSE precludes any serological test for the detection of antibodies.

For surveillance, a number of rapid tests on brain samples have been developed and approved by the European Union. These include the Western Blot test (detection of PrPres), Luminescence immunoassay (detection of disease specific prion proteins), and Chemiluminescent ELISA test.

Differential diagnosis: hypomagnesemia, nervous acetonemia, lead poisoning, intracranial tumours, and infectious diseases such as rabies, listeriosis , Aujeszky’s disease and cerebro-cortical-necrosis (CCN).

Treatment

There is currently no vaccine or treatment protocol for this disease.

Control

BSE is extremely difficult to control due to its long incubation period and the fact that the altered prions are extremely resistant to heat and chemicals. Stringent preventive measures are in place to stop the spread of the disease, prevent cattle and human exposure and to eradicate BSE from the animal population.

The most important of these measures has been the feed ban issued in 1988, prohibiting the feeding of ruminant derived meat and bone meal (MBM) to ruminants [9] and the adoption of the ban by the EU in 1994.

Post mortem testing schemes and culling of infected cohort animals have also helped to reduce the spread of BSE. So far they have resulted in a significant decrease in the number of BSE cases in the UK and other affected countries. Currently, the number of cases in the UK is decreasing.

For countries that are BSE free, preventative measures are ruminant to ruminant feed ban, import controls and surveillance.

To reduce the risk to humans developing variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD) all visible nervous and lymphatic tissue that are classified as specified risk materials (SRM) are removed during the processing of cattle as well as the removal of any suspect animals from the human food chain.

Specified risk material of cattle includes: brain, eyes (retina), trigeminal ganglia, the spinal cord, the dorsal root ganglia, mesentery, intestines (duodenum to rectum) and tonsils.

SRM in sheep and goats include: spleen, ileum, spinal cord, brain, eyes and tonsils.

In 1996, cattle over the age of 30 months were eliminated from the food chain within the UK under the ‘over thirty months scheme’ (OTMS). This ban has now been lifted and it is now compulsory to test all cattle over the age of 48months for BSE.

| Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy Learning Resources | |

|---|---|

Test your knowledge using flashcard type questions |

BSE in Cattle Flashcards |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Prusiner, S.B. (1997) Prion diseases. In: Viral pathogenesis. Nathanson, et al., eds. Philadelphia, USA: Lippin-Cott-Raven Publishers, 871-911.

- ↑ Wilesmith, J.W., Ryan, J.B.M. (1997) Absence of BSE in the offspring of pedigree suckler cows affected by BSE in Great Britain. Veterinary Record, 141(10):250-251; 5 ref.

- ↑ Donnelly ,C.A. (1998) Maternal transmission of BSE: interpretation of the data on the offspring of BSE-affected pedigree suckler cows. Veterinary Record, 142(21):579-580; 9 ref..

- ↑ Fatzer, R., Ehrensperger, F., Heim, D., Schmidt, J., Schmitt, A., Braun, U., Vandevelde, M. (1998) Investigation of 182 offspring of cows with bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in Switzerland. Part 2. Epidemiological and neuropathological results. Schweizer Archiv für Tierheilkunde, 140(6):250-254; 14 ref.

- ↑ Schreuder BEC (1998) Epidemiological aspects of scrapie and BSE including a risk assessment study. ISBN 90-393-1636-8. Thesis University of Utrecht

- ↑ OIE (2000) Bovine spongiform encephalopathy. In: OIE Manual of Standards for diagnostic tests and vaccines. Office International des Epizooties (edition 4), 457-460.

- ↑ Benbow, G.M. (1990) Zoo animal BSE. Vet. Rec. 126:441.

- ↑ Collinge, J. (2001) Prion diseases of humans and animals: their causes and molecular basis. Ann. Rev. Neurosci. 24:519-550.

- ↑ Hoinville, L.J. (1994) Decline in the incidence of BSE in cattle born after the introduction of the 'feed ban'. Veterinary Record, 134(11):274-275; 12 ref.

|

This article was originally sourced from The Animal Health & Production Compendium (AHPC) published online by CABI during the OVAL Project. The datasheet was accessed on 30 May 2011. |

Links

List of Member Countries' BSE risk status from the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE)

| This article has been peer reviewed but is awaiting expert review. If you would like to help with this, please see more information about expert reviewing. |

Error in widget FBRecommend: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt697b90c69ef3e7_19059920 Error in widget google+: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt697b90c6aa05c8_22748646 Error in widget TwitterTweet: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt697b90c6bb3873_10701194

|

| WikiVet® Introduction - Help WikiVet - Report a Problem |