Difference between revisions of "Female Reproduction - Donkey"

| (11 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{review}} | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Reproductive anatomy peculiarities== | |

| + | [[Image:Anatomy jenny donkey.jpg|left|thumb|200px|<small><center>General anatomy of the jenny’s genital organs. 1) ovary, 2) uterine horn, 3) broad ligament, 4) cervix, 5) vagina, 6) vulva, 7) prominent clitoris.(Image courtesy of [http://drupal.thedonkeysanctuary.org.uk The Donkey Sanctuary])</center></small>]] | ||

| + | [[Image:External genitalia jenny donkey.jpg|right|thumb|200px|<small><center>External genitalia of the jenny, showing the small and tight vulva with prominent clitoris and small perineal body. (Image courtesy of [http://drupal.thedonkeysanctuary.org.uk The Donkey Sanctuary])</center></small>]] | ||

| − | ''' | + | The general anatomy of the reproductive organs in the jenny is similar to that of the mare. Some peculiarities of the anatomy |

| + | of the reproductive tract have been reported that may be of importance for the practising veterinarian. Donkey breeds present a wide variation in size and disposition. Miniature and small African breeds may be challenging as far as ''per rectum'' palpation | ||

| + | and ultrasonography of the reproductive organs. Techniques used for miniature horses may be adapted for the examination of these small individuals (Purdy, 2005; Tibary, 2004). | ||

| − | '''[[ | + | The jenny’s '''cervix is longer''' than that of the mare and is '''coneshaped'''. It protrudes into the vagina and forms a '''deeper fornix'''. This peculiarity makes manipulation of the cervix for uterine flushing or other techniques requiring access to the uterine cavity during dioestrus rather difficult. Also, the narrowness of the cervical canal may '''predispose to ''intra-partum'' or ''post-partum'' cervical laceration''' in cases of dystocia (Vendramini ''et al'', 1998). The '''vulvar lips are small and usually very tight'''. Pneumovagina and urovagina are not common. |

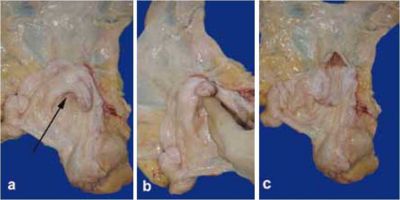

| + | [[Image:Cervix jenny.jpg|center|thumb|400px|<small><center>Anatomy of the cervix in the jenny: a) deep fornix (arrow), b) and c) excessive length and protrusion into the vaginal cavity. (Image courtesy of [http://drupal.thedonkeysanctuary.org.uk The Donkey Sanctuary])</center></small>]] | ||

| + | ==Seasonality== | ||

| − | + | <u>Ovarian activity in the jenny starts between 8 and 24 months of age</u>. This great variability can be explained by factors such as breed, nutrition, health, temperature and photoperiod. Seasonality of ovarian activity is variable and is likely to be influenced by photoperiod as well as nutrition and temperature. Scientific studies regarding seasonality present some discrepancy. | |

| − | ''' | + | Jennies may cycle all year around in the southern USA. In Wisconsin (latitude 43°N), the seasonality of the jenny seems to be less pronounced than that of mares. At this latitude, 64% of females were found to be cycling in December. Seasonal anoestrus lasts between 39 to 72 days (Ginther ''et al'', 1987). |

| − | ''' | + | A marked seasonality in which 54% of the females present an anoestrus has been reported in Brazil (latitude 19°51' 06"S). Anoestrus season lasts 166.3 ± 63.2 days (Henry ''et al'' ,1987). Seasonality has also been described in Mexico (Orozco Hernandez ''et al'', 1992). In Morocco, our field observations show that the peak birthing season is March through May with some sporadic births occurring in February and from June until September. Studies in Ethiopia show that the rainy season (''i.e.'' increased |

| − | + | food availability) is associated with higher sexual activity, follicular growth and incidence of ovulation in free-ranging tropical jennies (Lemma ''et al'', 2006a). Ovarian activity in these jennies is highly correlated with body condition (Lemma ''et al'', 2006b). | |

| − | == | + | ==Oestrous cycle== |

| − | [[ | + | [[Image:Mating behaviour jenny donkey.jpg|right|thumb|300px|<small><center>Mating behaviour, showing typical ‘yawning’ or ‘mouth clapping’ of the oestrous female during mating.(Image courtesy of [http://drupal.thedonkeysanctuary.org.uk The Donkey Sanctuary])</center></small>]] |

| + | [[Image:Table 1 oestrus cycle donkey.jpg|right|thumb|400px|<small><center>(Image courtesy of [http://drupal.thedonkeysanctuary.org.uk The Donkey Sanctuary])</center></small>]] | ||

| + | <u>The oestrous cycle is slightly longer than that of the mare and normally lasts 23 to 24 days, but can range from 13 to 31 days</u> (Table 1). '''Oestrus lasts 3 to 15 days'''. Signs of oestrus include '''tail raising, urination stance, winking of | ||

| + | the clitoris, ears back, mounting other females, standing to be mounted''' and''' vulvar oedema'''. These signs intensify in the presence of the male and are accompanied by a '''yawning reflex''' with the neck extended (jaws clamping, yawning) (Henry ''et al'', 1987; Fielding, 1988; Tibary and Bakkoury, 1994). | ||

| + | '''Follicular dominance''' is established at a diameter of about '''25 mm'''. Most dominant follicles are about 27 mm in diameter at the onset of oestrus. Follicular growth averages 2.7 mm per day (Dadarwal et al, 2004). <u>Ovulation takes place during the last 24 hours of heat.</u> | ||

| − | + | Behavioural oestrus persists a few hours (0.7-0.8 days) after ovulation (Vandeplassche ''et al'', 1981, Henry ''et al'', 1987). The average size of the preovulatory follicle may be breed-dependent. It is 30 to 33 mm in the Poitou and 35 to 40 (39.4 mm) in the Pega and Mammoth (Lun ''et al'', 1998). North African jennies may ovulate at a smaller size (32 mm). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | An incidence of '''double, triple and quadruple ovulations''' of respectively 25.5%, 10.5% and 1.1% has been reported in some breeds. The incidence of multiple ovulations generally ranges from 5 to 32 % (Vandeplassche ''et al'', 1981; Ginther ''et al'', 1987; Meira ''et al'', 1995; Blanchard and Taylor, 2005). Double ovulation incidence can be as high as 37%. Incidence of multiple ovulations can reach 61% in mammoth jennies (Blanchard ''et al'', 1999). The majority (75%) of double ovulations are asynchronous with the interval between ovulations ranging from one to four days in general and up to eleven days in some instances. The incidence of double ovulations and twinning is extremely low in the North African donkey. | ||

| + | In general, jennies are in oestrus until occurrence of the second ovulation (Vandeplassche ''et al'', 1981). Twin births are rare, but have been reported in higher numbers in the Mammoth jenny and in the dairy breed Ragusana in Sicily (Mancuso ''et al'', 2004). The approach to twin management should be similar to that used in mares. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The '''inter-ovulatory period''' is significantly longer in jennies than in mares (Vandeplassche ''et al'', 1981; Ginther ''et al'', 1987; Meira ''et al'', 1995). The average life span of the ''corpus luteum'' is 15 to 20 days (19.3 ±0.6 in standard jennies (Vandeplassche ''et al'', 1981) and 17.4 ± 2.6 days in mammoth jennies (Blanchard ''et al'', 1999). The inter-ovulatory period is 24.9 ± 0.7 days for standard and 23.3 ± 2.6 days for mammoth jennies (Vandeplassche ''et al'', 1981; Blanchard ''et al'', 1999). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The ultrasonographic characteristics of the uterus at different phases of the oestrus cycle are similar to those described for the mare (Lemma ''et al'', 2006). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Pregnancy== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ultrasonographic characteristics of the asinine early pregnancy have been described, and present several similarities with the horse (Meira ''et al'', 1998; Carluccio ''et al'', 2005). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Early pregnancy diagnosis=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Ultrasound pregnancy diagnosis jenny donkey.jpg|right|thumb|300px|<small><center>Assessment of foetal well-being by trans-abdominal ultrasonography. In late pregnancy this technique requires clipping the hair over an area from the xyphoid to the udder and the use of a 3.5 MHz sector transducer. (Image courtesy of [http://drupal.thedonkeysanctuary.org.uk The Donkey Sanctuary])</center></small>]] | ||

| + | The '''embryonic vesicle can be detected by transrectal ultrasonography from days 10 to 12 post-ovulation (11.5 ± 0.9 days)'''. <u>Fixation of the embryonic vesicle occurs 15.5 ± 1.4 days after ovulation.</u> The mean growth rate of the embryo is 3 to 3.5 mm per day until 18 days. The vesicle becomes irregular and grows more slowly (0.4 to 0.5 mm per day) from day 19 until day 29. | ||

| + | '''The heartbeat is detected at 23.5 ±1.3 days.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Secondary ''corpora lutea'' are formed between days 38 and 46 (41.8 ±1).'''Plasma progesterone''' increases in the first 19 days to about 19.9 ng/ml then decreases to 12 ng/ml at day 30. Another increase is seen between day 30 to 40 (17 ng/ml). Progesterone gradually declines between 110 and 160 days and remains at about 6 ng/ml. '''Chorionic gonadotropin''' is secreted after day 36 of pregnancy (Meira ''et al'', 1998a; Meira ''et al'', 1998b). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Foetal well-being and the foeto-placental unit can be evaluated in the same manner as for the horse. In late pregnancy, the foetus is generally very deep and cranially situated in the abdomen. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Parturition and ''post-partum''== | ||

| + | [[Image:Late term jenny donkey.jpg|right|thumb|300px|<small><center>Late term pregnant female showing mammary development and ventral oedema. Although this development takes place primarily in the last 48 hours of pregnancy, it may be present in some females up to two weeks before parturition. (Image courtesy of [http://drupal.thedonkeysanctuary.org.uk The Donkey Sanctuary])</center></small>]] | ||

| + | '''The length of pregnancy is 365 to 376 days''' but extreme variations ranging from 340 to 395 days have been reported (Kohli ''et al'', 1957; Tibary and Bakkoury, 1994; Macusoe ''et al'', 2004). Male foetuses are carried on average one day longer. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Prediction of foaling''' is based on '''udder development and waxing''', which seems to reliably start 24 to 48 hours before foaling. The '''calcium concentration in mammary secretions''' increases steadily in the last week of pregnancy and surpasses 500 ppm about 24 hours before foaling. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Parturition presents in the classical three stages:''' | ||

| + | [[Image:Parturition stage 2 jenny donkey.jpg|right|thumb|300px|<small><center>Stage 2 of parturition: a) and b) The allantochorion has ruptured about five minutes before. The foal can be seen through the amniotic sac. (Image courtesy of [http://drupal.thedonkeysanctuary.org.uk The Donkey Sanctuary])</center></small>]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Parturition end of stage 2 jenny donkey.jpg|right|thumb|200px|<small><center>c) End of stage 2 of parturition (expulsion of the foetus): The entire stage 2 lasts about 20 minutes (5-35 minutes). (Image courtesy of [http://drupal.thedonkeysanctuary.org.uk The Donkey Sanctuary])</center></small>]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Parturition stage 3 jenny donkey.jpg|right|thumb|200px|<small><center>Stage 3 of parturition: This stage usually lasts around one hour but may take up to six hours. (Image courtesy of [http://drupal.thedonkeysanctuary.org.uk The Donkey Sanctuary])</center></small>]] | ||

| + | * '''Stage 1:''' (preparation for labour) Characterized by increased restlessness, isolation from herd mates and frequent alternation between standing and lying down. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * '''Stage 2:''' (expulsion of the foetus) starts with the rupture of the allantochorion and appearance of the amniotic sac at the vulva. This is usually completed in 10 to 30 minutes with the female in lateral recumbency. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * '''Stage 3:''' (expulsion of placenta) usually completed in one hour but may take up to six hours. Possible retention of the placenta should be closely monitored and treated if the placenta is not passed by six hours. Treatment with oxytocin intravenously (in lactate ringer) or intramuscularly is effective. However, jennies with '''retained placenta''' should also be monitored for '''hypocalcaemia'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Parturition can be induced''' by the administration of small doses of oxytocin. Criteria for induction of parturition are similar to those described for the mare, that is, pregnancy length >340 days, evidence of mammary development and waxing, change in pre-colostrum electrolyte and no abnormalities (Pashen, 1980). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Donkey '''dystocia''' cases have been reported, but their true incidence and nature is not known. Malformations such as '''''schistosomus reflexus''''' and''' foetal ankylosis''' have been reported as causes of dystocia (Dubbin ''et al'', 1990). In miniature donkeys, dystocia may result following abortion due to foetal malformation. In equines, the uterus should be able to regulate foetal growth and reduce the rate of dystocia due to foetal-maternal disproportion. However, an increased rate of dystocia is commonly feared when jennies are bred to stallions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Dystocia risks are increased in miniature donkeys''' because of the domed large forehead of some foals. Relief of dystocia is best accomplished under anaesthesia, with the jenny’s hindquarters suspended. '''Caesarean section''' is preferable to foetotomy. Long obstetrical manipulations have been associated with vaginal adhesions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Uterine involution''' is still poorly studied in asinine species. One study on Catalonian jennies reported that gross uterine involution is completed by 22.5 ± 1.7 days ''post-partum'' (range of 18 to 27 days) (Dadarwal ''et al'', 2004). Vaginal discharge (clear odourless lochia) was present for up to seven days and intrauterine fluid was detected by ultrasound for up to 18 days in some females. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Foal heat''' occurs 8.6 days after foaling, but periods of 2 to 69 days have been reported. Dardawal ''et al'' (2004) found that, on the day of parturition, several 10 to 15 mm follicles are present and by 5 to 12 days ''post-partum'' at least one follicle has reached 25 mm in diameter. Behavioural oestrus seems to be less pronounced with the first ''post-partum'' ovulation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Most jennies will ovulate between 13 to 17 days ''post-partum''. Extended periods of follicular activity without ovulation may be observed in some females. The interaction between ''post-partum'' cyclicity, body condition and lactation has not been investigated. In a study from 1957 in India, the mean interval from parturition to fertilization was found to be 162.5 ± 6.7 days | ||

| + | (Kohli ''et al'', 1957). | ||

| + | |||

| + | There are very few studies on '''nutritional requirements''' for optimal fertility, pregnancy needs and lactation. In one study, jennies lost abut 1% of their body weight at foaling and a further 0.5 to 1% during lactation (Eley and French, 1994). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Donkey '''neonate survival''' is often described as a major problem in developing countries. This high mortality may be due to poor rearing conditions (''post-partum'' care) as well as poor colostral protection. The effect of nutrition and management on foal growth and survival has not been fully studied. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In a free-ranging population, jennies may continue to nurse their foals until ten months of age (French, 1998). Feed supplementation along with anthelmintic treatment during late pregnancy and lactation has been associated with better survival of foals in Ethiopia (Mengistu ''et al'', 2005). This may be due to increased mammary function and prevention of failure of passive transfer. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Tibary, A., Sghiri, A. & Bakkoury, M. (2008) Reproduction In Svendsen, E.D., Duncan, J. and Hadrill, D. (2008) ''The Professional Handbook of the Donkey'', 4th edition, Whittet Books, Chapter 17 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | * Blanchard, T.L., Taylor, T.S. (2005). ‘Oestrous Cycle Characteristics of Donkeys with Emphasis on Standard and Mammoth Donkeys’. in: ''Veterinary Care of Donkeys''. N.S. Matthews and T.S. Taylor (eds). | ||

| + | * Blanchard, T.L., Taylor, T.S., and Love, C.L. (1999). ‘Estrous cycle characteristics and response to estrus synchronization in mammoth asses (''Equus asinus americanus'')’. ''Theriogenology'' 52. pp 827-834. | ||

| + | * Carluccio, A., Villani, M., Contri, A., Tosi, U., and Battocchio, M. (2004). ‘Preliminary study on some seminal and testicular morphometric characteristics in Martina Franca jackass’. ''Ippologia'' 15. pp 23-26. | ||

| + | * Carluccio, A., Villani, M., Contri, A., Tosi, U., and Veronesi, M.C. (2004).‘Ultrasonographic evaluation of the early pregnancy in Martina Franca jennies’. ''Ippologia'' 16. pp 31-35. | ||

| + | * Dadarwal, D., Tandon, S.N., Purohit, G.N., and Pareek, P.K. (2004). ‘Ultrasonographic evaluation of uterine involution and post-partum follicular dynamics of French Jennies (''Equus asinus'')’. ''Theriogenology ''62. pp 257-264. | ||

| + | * Dubbin, E.S., Welker, F., Veit, H., Modransky, P.D., Talley, M.R., Vandeplassche, M., and Salah-Osman-Idris, M.B. (1990). ‘Dystocia attributable to a fetal monster resembling schistosomus reflexus in a donkey’. ''Journal of the American Veterinary Association'' 197. pp 605-607. | ||

| + | * Eley, J.L., French, J.M. (1994). ‘Bodyweight changes in pregnant and lactating donkey mares and their foals’. ''Veterinary Record'' 134. p 627. | ||

| + | * Fielding, D. (1988). ‘Reproductive characteristics of the jenny donkey - ''Equus asinus'': a review’. ''Tropical Animal Health and Production'' 20. pp 161-166. | ||

| + | * French, J.M.(1998). ‘Mother-offspring relationships in donkeys’. ''Applied Animal Behaviour Science'' 60. pp 253-258. | ||

| + | * Ginther, O.J., Scrabam, S.T., and Bergfelt, D.R. (1987). ‘Reproductive seasonality of the jenny’. ''Theriogenology'' 27. pp 587-592. | ||

| + | * Henry, M., Figueiredo, A.E.F., Palhares, M.S., and Coryn, M. (1987). ‘Clinical and endocrine aspects of the estrous cycle in donkeys (''Equus asinus'')’. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility Suppl.35. pp 297-303. | ||

| + | * Kohli, M.L., Suri, K.R. (1957). ‘Studies on reproductive efficiency in donkey mares’. ''Indian J Vet. Sci.'' 27. pp 133-138. | ||

| + | * Kohli, M.L., Suri, K.R., and Chatter, J.I.A. (1957). ‘Studies on the gestation length and breeding age in donkey mares’. ''Indian Vet J.'' 34, pp 344-348. | ||

| + | * Lemma, A., Bekana, M., Schwartz, H.J., and Hildebrant, T. (2006). ‘Ultrasonographic study of ovarian activities in the tropical jenny during the seasons of high and low sexual activity’. ''Journal of Equine Veterinary Science ''26. pp 18-22. | ||

| + | * Lemma, A., Bekana, M. , Schwartz, H.J., and Hildebrant, T. (2006) ‘The effect of body condition on ovarian activity of free ranging tropical jennies (''Equus asinus'')’. ''Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series A- Physiology and Pathology Clinical Medicine'' 53. pp 1-4. | ||

| + | * Lun, S., He, C., Zhang, Y., Chen, Z., Hu, W., Lu, S., Jia, W., and Zhang, Q. (1998). ‘Preliminary study on development of follicles and formation of corpus luteum of the jenny and mare by ultrasonography’. ''Acta Veterinaria et Zootechnica Sinica'' 29. pp 419-425. | ||

| + | * Mancuso, R., Torrisi, C., and Catone, G. (2004). ‘Experiences in the management of the reproductive activity of dairy jennie-ass’. ''Ippologia'' 15. pp 5-9. | ||

| + | * Meira, C.,Ferreira, J.C.P., Papa, F.O., and Henry, M. (1995). ‘Study of the estrous cycle in donkeys (''Equus asinus'') using ultrasonography and plasma progesterone concentrations’. ''Biol Reprod Monograph'' 1. pp 403-410. | ||

| + | * Meira, C., Ferreira, J.C.P. , Papa, F.O., and Henry, M. (1998). ‘Ovarian activity and plasma concentrations of progesterone and estradiol during pregnancy in jennies’. ''Theriogenology'' 49. pp 1465-1473. | ||

| + | * Meira, C., Ferreira, J.C.P., Papa, F.O., and Henry, M. (1998). ‘Ultrasonographic evaluation of the conceptus from 10 days to 60 of pregnancy in jennies’. ''Theriogenology'' 49. pp 1475-1482. | ||

| + | * Mengistu, A., Smith, D.G., Yoseph, S., Nega,T., Zewdie, W. , Kassahun, W.G., Taye, B., and Firew, T. (2005). ‘The effect of providing feed supplementation and anthelmintic to donkeys during late pregnancy and lactation on live weight and survival of dams and their foals in central Ethiopia’. ''Tropical Animal Health and Production'' 37 (supplement 1). pp 21-33. | ||

| + | * Orozco Hernandez, J.L., Escobar Medina, F.J., and De La Colina Flores, F. (1992). ‘Ovarian activity in the mare and the female donkey during days with less light’. ''Veterinaria Mexico'' 23. pp 47-50. | ||

| + | * Pashen, R.L. (1980). ‘Low doses of oxytocin can induce foaling at term’. ''Eq. Vet. J.'' 12. pp 85-87. | ||

| + | * Purdy, S.R. (2005a). ‘Artificial Insemination for Miniature Donkeys’. in: ''Veterinary Care of Donkeys.'' N.S. Matthews and T.S. Taylor (eds). International Veterinary Information Service, Ithaca NY (www.ivis.org), 20 Apr, 2005; A2924.0405. | ||

| + | * Purdy, S.R. (2005b). ‘Ultrasound examination of the female miniature donkey reproductive tract’. in: ''Veterinary Care of Donkeys''. N.S. Matthews and T.S. Taylor (eds). International Veterinary information Service, Ithaca NY (www.ivis.org), last updated: 11 May 2005; A2925.0505. | ||

| + | * Tibary, A. (2004). ‘Reproductive patterns in donkeys and minature horses’. Proceedings of the North American Veterinary Conference, Orlando, Florida, 17-21 January. pp 231-233, 2004. | ||

| + | * Tibary, A., Bakkoury, M.(eds). (1994). ‘Particularités de la reproduction chez les autres espèces équines’. ''Reproduction équine, Tome I: La jument.'' Actes Editions 1994. pp 385-400. | ||

| + | * Vandeplassche, G.M., Wesson, J.A., and Ginther, O.J. (1981). ‘Behavioral, follicular and gonadotropin changes during estrous cycle in donkeys’. ''Theriogenology'' 16. pp 239-249. | ||

| + | * Vendramini, O.K., Guintard, C., Moreau, J., and Tainturier, D. (1998). ‘Cervix conformation: a first anatomical approach in Baudet du Poitou jenny asses’. ''Animal Science'' 66. pp 741-744. | ||

{{toplink | {{toplink | ||

| Line 31: | Line 127: | ||

|pagetype = Donkey | |pagetype = Donkey | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {{ | + | |

| − | | | + | [[Category:Donkey]] |

| − | + | ||

| + | {{toplink | ||

| + | |titleborder=E0EEEE | ||

| + | |linkpage = Sponsors | ||

| + | |linktext = This page was sponsored and content provided by ''THE DONKEY SANCTUARY'' | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Revision as of 21:33, 22 February 2010

| This article has been peer reviewed but is awaiting expert review. If you would like to help with this, please see more information about expert reviewing. |

Reproductive anatomy peculiarities

The general anatomy of the reproductive organs in the jenny is similar to that of the mare. Some peculiarities of the anatomy of the reproductive tract have been reported that may be of importance for the practising veterinarian. Donkey breeds present a wide variation in size and disposition. Miniature and small African breeds may be challenging as far as per rectum palpation and ultrasonography of the reproductive organs. Techniques used for miniature horses may be adapted for the examination of these small individuals (Purdy, 2005; Tibary, 2004).

The jenny’s cervix is longer than that of the mare and is coneshaped. It protrudes into the vagina and forms a deeper fornix. This peculiarity makes manipulation of the cervix for uterine flushing or other techniques requiring access to the uterine cavity during dioestrus rather difficult. Also, the narrowness of the cervical canal may predispose to intra-partum or post-partum cervical laceration in cases of dystocia (Vendramini et al, 1998). The vulvar lips are small and usually very tight. Pneumovagina and urovagina are not common.

Seasonality

Ovarian activity in the jenny starts between 8 and 24 months of age. This great variability can be explained by factors such as breed, nutrition, health, temperature and photoperiod. Seasonality of ovarian activity is variable and is likely to be influenced by photoperiod as well as nutrition and temperature. Scientific studies regarding seasonality present some discrepancy.

Jennies may cycle all year around in the southern USA. In Wisconsin (latitude 43°N), the seasonality of the jenny seems to be less pronounced than that of mares. At this latitude, 64% of females were found to be cycling in December. Seasonal anoestrus lasts between 39 to 72 days (Ginther et al, 1987).

A marked seasonality in which 54% of the females present an anoestrus has been reported in Brazil (latitude 19°51' 06"S). Anoestrus season lasts 166.3 ± 63.2 days (Henry et al ,1987). Seasonality has also been described in Mexico (Orozco Hernandez et al, 1992). In Morocco, our field observations show that the peak birthing season is March through May with some sporadic births occurring in February and from June until September. Studies in Ethiopia show that the rainy season (i.e. increased food availability) is associated with higher sexual activity, follicular growth and incidence of ovulation in free-ranging tropical jennies (Lemma et al, 2006a). Ovarian activity in these jennies is highly correlated with body condition (Lemma et al, 2006b).

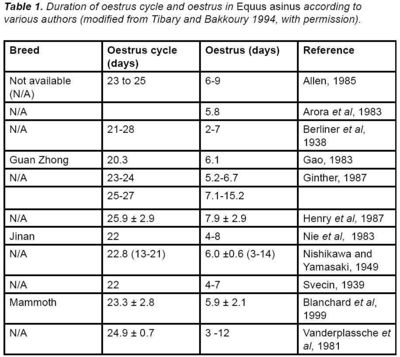

Oestrous cycle

The oestrous cycle is slightly longer than that of the mare and normally lasts 23 to 24 days, but can range from 13 to 31 days (Table 1). Oestrus lasts 3 to 15 days. Signs of oestrus include tail raising, urination stance, winking of the clitoris, ears back, mounting other females, standing to be mounted and vulvar oedema. These signs intensify in the presence of the male and are accompanied by a yawning reflex with the neck extended (jaws clamping, yawning) (Henry et al, 1987; Fielding, 1988; Tibary and Bakkoury, 1994).

Follicular dominance is established at a diameter of about 25 mm. Most dominant follicles are about 27 mm in diameter at the onset of oestrus. Follicular growth averages 2.7 mm per day (Dadarwal et al, 2004). Ovulation takes place during the last 24 hours of heat.

Behavioural oestrus persists a few hours (0.7-0.8 days) after ovulation (Vandeplassche et al, 1981, Henry et al, 1987). The average size of the preovulatory follicle may be breed-dependent. It is 30 to 33 mm in the Poitou and 35 to 40 (39.4 mm) in the Pega and Mammoth (Lun et al, 1998). North African jennies may ovulate at a smaller size (32 mm).

An incidence of double, triple and quadruple ovulations of respectively 25.5%, 10.5% and 1.1% has been reported in some breeds. The incidence of multiple ovulations generally ranges from 5 to 32 % (Vandeplassche et al, 1981; Ginther et al, 1987; Meira et al, 1995; Blanchard and Taylor, 2005). Double ovulation incidence can be as high as 37%. Incidence of multiple ovulations can reach 61% in mammoth jennies (Blanchard et al, 1999). The majority (75%) of double ovulations are asynchronous with the interval between ovulations ranging from one to four days in general and up to eleven days in some instances. The incidence of double ovulations and twinning is extremely low in the North African donkey.

In general, jennies are in oestrus until occurrence of the second ovulation (Vandeplassche et al, 1981). Twin births are rare, but have been reported in higher numbers in the Mammoth jenny and in the dairy breed Ragusana in Sicily (Mancuso et al, 2004). The approach to twin management should be similar to that used in mares.

The inter-ovulatory period is significantly longer in jennies than in mares (Vandeplassche et al, 1981; Ginther et al, 1987; Meira et al, 1995). The average life span of the corpus luteum is 15 to 20 days (19.3 ±0.6 in standard jennies (Vandeplassche et al, 1981) and 17.4 ± 2.6 days in mammoth jennies (Blanchard et al, 1999). The inter-ovulatory period is 24.9 ± 0.7 days for standard and 23.3 ± 2.6 days for mammoth jennies (Vandeplassche et al, 1981; Blanchard et al, 1999).

The ultrasonographic characteristics of the uterus at different phases of the oestrus cycle are similar to those described for the mare (Lemma et al, 2006).

Pregnancy

Ultrasonographic characteristics of the asinine early pregnancy have been described, and present several similarities with the horse (Meira et al, 1998; Carluccio et al, 2005).

Early pregnancy diagnosis

The embryonic vesicle can be detected by transrectal ultrasonography from days 10 to 12 post-ovulation (11.5 ± 0.9 days). Fixation of the embryonic vesicle occurs 15.5 ± 1.4 days after ovulation. The mean growth rate of the embryo is 3 to 3.5 mm per day until 18 days. The vesicle becomes irregular and grows more slowly (0.4 to 0.5 mm per day) from day 19 until day 29. The heartbeat is detected at 23.5 ±1.3 days.

Secondary corpora lutea are formed between days 38 and 46 (41.8 ±1).Plasma progesterone increases in the first 19 days to about 19.9 ng/ml then decreases to 12 ng/ml at day 30. Another increase is seen between day 30 to 40 (17 ng/ml). Progesterone gradually declines between 110 and 160 days and remains at about 6 ng/ml. Chorionic gonadotropin is secreted after day 36 of pregnancy (Meira et al, 1998a; Meira et al, 1998b).

Foetal well-being and the foeto-placental unit can be evaluated in the same manner as for the horse. In late pregnancy, the foetus is generally very deep and cranially situated in the abdomen.

Parturition and post-partum

The length of pregnancy is 365 to 376 days but extreme variations ranging from 340 to 395 days have been reported (Kohli et al, 1957; Tibary and Bakkoury, 1994; Macusoe et al, 2004). Male foetuses are carried on average one day longer.

Prediction of foaling is based on udder development and waxing, which seems to reliably start 24 to 48 hours before foaling. The calcium concentration in mammary secretions increases steadily in the last week of pregnancy and surpasses 500 ppm about 24 hours before foaling.

Parturition presents in the classical three stages:

- Stage 1: (preparation for labour) Characterized by increased restlessness, isolation from herd mates and frequent alternation between standing and lying down.

- Stage 2: (expulsion of the foetus) starts with the rupture of the allantochorion and appearance of the amniotic sac at the vulva. This is usually completed in 10 to 30 minutes with the female in lateral recumbency.

- Stage 3: (expulsion of placenta) usually completed in one hour but may take up to six hours. Possible retention of the placenta should be closely monitored and treated if the placenta is not passed by six hours. Treatment with oxytocin intravenously (in lactate ringer) or intramuscularly is effective. However, jennies with retained placenta should also be monitored for hypocalcaemia.

Parturition can be induced by the administration of small doses of oxytocin. Criteria for induction of parturition are similar to those described for the mare, that is, pregnancy length >340 days, evidence of mammary development and waxing, change in pre-colostrum electrolyte and no abnormalities (Pashen, 1980).

Donkey dystocia cases have been reported, but their true incidence and nature is not known. Malformations such as schistosomus reflexus and foetal ankylosis have been reported as causes of dystocia (Dubbin et al, 1990). In miniature donkeys, dystocia may result following abortion due to foetal malformation. In equines, the uterus should be able to regulate foetal growth and reduce the rate of dystocia due to foetal-maternal disproportion. However, an increased rate of dystocia is commonly feared when jennies are bred to stallions.

Dystocia risks are increased in miniature donkeys because of the domed large forehead of some foals. Relief of dystocia is best accomplished under anaesthesia, with the jenny’s hindquarters suspended. Caesarean section is preferable to foetotomy. Long obstetrical manipulations have been associated with vaginal adhesions.

Uterine involution is still poorly studied in asinine species. One study on Catalonian jennies reported that gross uterine involution is completed by 22.5 ± 1.7 days post-partum (range of 18 to 27 days) (Dadarwal et al, 2004). Vaginal discharge (clear odourless lochia) was present for up to seven days and intrauterine fluid was detected by ultrasound for up to 18 days in some females.

Foal heat occurs 8.6 days after foaling, but periods of 2 to 69 days have been reported. Dardawal et al (2004) found that, on the day of parturition, several 10 to 15 mm follicles are present and by 5 to 12 days post-partum at least one follicle has reached 25 mm in diameter. Behavioural oestrus seems to be less pronounced with the first post-partum ovulation.

Most jennies will ovulate between 13 to 17 days post-partum. Extended periods of follicular activity without ovulation may be observed in some females. The interaction between post-partum cyclicity, body condition and lactation has not been investigated. In a study from 1957 in India, the mean interval from parturition to fertilization was found to be 162.5 ± 6.7 days (Kohli et al, 1957).

There are very few studies on nutritional requirements for optimal fertility, pregnancy needs and lactation. In one study, jennies lost abut 1% of their body weight at foaling and a further 0.5 to 1% during lactation (Eley and French, 1994).

Donkey neonate survival is often described as a major problem in developing countries. This high mortality may be due to poor rearing conditions (post-partum care) as well as poor colostral protection. The effect of nutrition and management on foal growth and survival has not been fully studied.

In a free-ranging population, jennies may continue to nurse their foals until ten months of age (French, 1998). Feed supplementation along with anthelmintic treatment during late pregnancy and lactation has been associated with better survival of foals in Ethiopia (Mengistu et al, 2005). This may be due to increased mammary function and prevention of failure of passive transfer.

References

- Tibary, A., Sghiri, A. & Bakkoury, M. (2008) Reproduction In Svendsen, E.D., Duncan, J. and Hadrill, D. (2008) The Professional Handbook of the Donkey, 4th edition, Whittet Books, Chapter 17

- Blanchard, T.L., Taylor, T.S. (2005). ‘Oestrous Cycle Characteristics of Donkeys with Emphasis on Standard and Mammoth Donkeys’. in: Veterinary Care of Donkeys. N.S. Matthews and T.S. Taylor (eds).

- Blanchard, T.L., Taylor, T.S., and Love, C.L. (1999). ‘Estrous cycle characteristics and response to estrus synchronization in mammoth asses (Equus asinus americanus)’. Theriogenology 52. pp 827-834.

- Carluccio, A., Villani, M., Contri, A., Tosi, U., and Battocchio, M. (2004). ‘Preliminary study on some seminal and testicular morphometric characteristics in Martina Franca jackass’. Ippologia 15. pp 23-26.

- Carluccio, A., Villani, M., Contri, A., Tosi, U., and Veronesi, M.C. (2004).‘Ultrasonographic evaluation of the early pregnancy in Martina Franca jennies’. Ippologia 16. pp 31-35.

- Dadarwal, D., Tandon, S.N., Purohit, G.N., and Pareek, P.K. (2004). ‘Ultrasonographic evaluation of uterine involution and post-partum follicular dynamics of French Jennies (Equus asinus)’. Theriogenology 62. pp 257-264.

- Dubbin, E.S., Welker, F., Veit, H., Modransky, P.D., Talley, M.R., Vandeplassche, M., and Salah-Osman-Idris, M.B. (1990). ‘Dystocia attributable to a fetal monster resembling schistosomus reflexus in a donkey’. Journal of the American Veterinary Association 197. pp 605-607.

- Eley, J.L., French, J.M. (1994). ‘Bodyweight changes in pregnant and lactating donkey mares and their foals’. Veterinary Record 134. p 627.

- Fielding, D. (1988). ‘Reproductive characteristics of the jenny donkey - Equus asinus: a review’. Tropical Animal Health and Production 20. pp 161-166.

- French, J.M.(1998). ‘Mother-offspring relationships in donkeys’. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 60. pp 253-258.

- Ginther, O.J., Scrabam, S.T., and Bergfelt, D.R. (1987). ‘Reproductive seasonality of the jenny’. Theriogenology 27. pp 587-592.

- Henry, M., Figueiredo, A.E.F., Palhares, M.S., and Coryn, M. (1987). ‘Clinical and endocrine aspects of the estrous cycle in donkeys (Equus asinus)’. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility Suppl.35. pp 297-303.

- Kohli, M.L., Suri, K.R. (1957). ‘Studies on reproductive efficiency in donkey mares’. Indian J Vet. Sci. 27. pp 133-138.

- Kohli, M.L., Suri, K.R., and Chatter, J.I.A. (1957). ‘Studies on the gestation length and breeding age in donkey mares’. Indian Vet J. 34, pp 344-348.

- Lemma, A., Bekana, M., Schwartz, H.J., and Hildebrant, T. (2006). ‘Ultrasonographic study of ovarian activities in the tropical jenny during the seasons of high and low sexual activity’. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 26. pp 18-22.

- Lemma, A., Bekana, M. , Schwartz, H.J., and Hildebrant, T. (2006) ‘The effect of body condition on ovarian activity of free ranging tropical jennies (Equus asinus)’. Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series A- Physiology and Pathology Clinical Medicine 53. pp 1-4.

- Lun, S., He, C., Zhang, Y., Chen, Z., Hu, W., Lu, S., Jia, W., and Zhang, Q. (1998). ‘Preliminary study on development of follicles and formation of corpus luteum of the jenny and mare by ultrasonography’. Acta Veterinaria et Zootechnica Sinica 29. pp 419-425.

- Mancuso, R., Torrisi, C., and Catone, G. (2004). ‘Experiences in the management of the reproductive activity of dairy jennie-ass’. Ippologia 15. pp 5-9.

- Meira, C.,Ferreira, J.C.P., Papa, F.O., and Henry, M. (1995). ‘Study of the estrous cycle in donkeys (Equus asinus) using ultrasonography and plasma progesterone concentrations’. Biol Reprod Monograph 1. pp 403-410.

- Meira, C., Ferreira, J.C.P. , Papa, F.O., and Henry, M. (1998). ‘Ovarian activity and plasma concentrations of progesterone and estradiol during pregnancy in jennies’. Theriogenology 49. pp 1465-1473.

- Meira, C., Ferreira, J.C.P., Papa, F.O., and Henry, M. (1998). ‘Ultrasonographic evaluation of the conceptus from 10 days to 60 of pregnancy in jennies’. Theriogenology 49. pp 1475-1482.

- Mengistu, A., Smith, D.G., Yoseph, S., Nega,T., Zewdie, W. , Kassahun, W.G., Taye, B., and Firew, T. (2005). ‘The effect of providing feed supplementation and anthelmintic to donkeys during late pregnancy and lactation on live weight and survival of dams and their foals in central Ethiopia’. Tropical Animal Health and Production 37 (supplement 1). pp 21-33.

- Orozco Hernandez, J.L., Escobar Medina, F.J., and De La Colina Flores, F. (1992). ‘Ovarian activity in the mare and the female donkey during days with less light’. Veterinaria Mexico 23. pp 47-50.

- Pashen, R.L. (1980). ‘Low doses of oxytocin can induce foaling at term’. Eq. Vet. J. 12. pp 85-87.

- Purdy, S.R. (2005a). ‘Artificial Insemination for Miniature Donkeys’. in: Veterinary Care of Donkeys. N.S. Matthews and T.S. Taylor (eds). International Veterinary Information Service, Ithaca NY (www.ivis.org), 20 Apr, 2005; A2924.0405.

- Purdy, S.R. (2005b). ‘Ultrasound examination of the female miniature donkey reproductive tract’. in: Veterinary Care of Donkeys. N.S. Matthews and T.S. Taylor (eds). International Veterinary information Service, Ithaca NY (www.ivis.org), last updated: 11 May 2005; A2925.0505.

- Tibary, A. (2004). ‘Reproductive patterns in donkeys and minature horses’. Proceedings of the North American Veterinary Conference, Orlando, Florida, 17-21 January. pp 231-233, 2004.

- Tibary, A., Bakkoury, M.(eds). (1994). ‘Particularités de la reproduction chez les autres espèces équines’. Reproduction équine, Tome I: La jument. Actes Editions 1994. pp 385-400.

- Vandeplassche, G.M., Wesson, J.A., and Ginther, O.J. (1981). ‘Behavioral, follicular and gonadotropin changes during estrous cycle in donkeys’. Theriogenology 16. pp 239-249.

- Vendramini, O.K., Guintard, C., Moreau, J., and Tainturier, D. (1998). ‘Cervix conformation: a first anatomical approach in Baudet du Poitou jenny asses’. Animal Science 66. pp 741-744.

|

|

|

|