Difference between revisions of "Vomiting"

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

Vomiting has potentially lethal effects in the monogastric animal. The effects are listed below. | Vomiting has potentially lethal effects in the monogastric animal. The effects are listed below. | ||

| − | |||

===Water Loss=== | ===Water Loss=== | ||

Revision as of 19:37, 29 December 2010

Overview

Vomiting has potentially lethal effects in the monogastric animal. The effects are listed below.

Water Loss

Fluid loss is evident as; An increased PCV or haematocrit, an increased total protein concentration or a prerenal azotaemia.

Gastric Electrolyte Loss

The main losses are of H+ and Cl-, and also K+. Electrolyte loss can potentially cause metabolic alkalosis, although this is only likely with disease which stops at the pylorus, e.g.: pyloric outflow obstruction. In cases where mild alkalosis occurs, homeostatic mechanisms produce a more alkaline urine to restore normal body pH. However, in severe metablolic alkalosis with marked dehydration, acidic urine may be produced. This is termed paradoxical aciduria. Because vomiting induceses hypokalaemia, there is an overriding stimulus in the kidney for Na+ (and therefore water) retention. Na+ can only be resorbed in exchange for H+, H++ is therefore excreted in the urine, causing it to be acidic. Vomiting also induces hypochloraemia, meaning bicarbonate rather than chloride is resorbed with the Na+ to maintain electrical neutrality. This perpetuates the alkalosis.

Vomiting does not occur in the ruminant although abomasal content may reflux into the forestomachs. Sequestration of secretions in the abomasum will have similar effects to pyloric outflow obstruction with vomiting in the monogastric animal. e.g. abomasal torsion. It also causes dehydration, hypochloraemia, hypokalaemia and metabolic alkalosis. Lesions in the small intestine can also lead to vomiting. Both gastric acid and pancreatic and intestinal bicarbonate secretions are lost, the animal consequently has a normal pH or may even be acidotic.

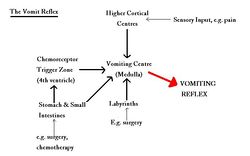

The Vomit Reflex

Emesis is the process of vomiting. Persistent vomiting can be exhausting and can lead to metabolic alkalosis, dehydration and electrolyte inbalances which may require fluid therapy. Extreme cases of persistent vomiting can lead to shock.

Vomiting includes retching and the action of the diaphragm. The diaphragm moves caudal to open the cardia and retching involves the abdominal and chest walls contracting. The gastrointestinal tract has protective stimuli to recognise harmful products ingested. The mechanoreceptors and chemoreceptors respond using viscerent afferent pathways. The medulla co-ordinates the process and the chemoreceptive trigger zone in the 4th ventricle responds to blood and CSF. Inputs are also recieved from the inner ear and higher centres.

Emetic agents can be used in cases of gastric obstruction and to remove non-corrosive poisons from the stomach (for corrosive poisons charcoal can be used which will help adsorb the substance and decrease its absorbtion into the GIT).

Emetic agents

Drugs cause emesis by irritating the gastric mucosa. Emetic drugs include the following;

- Histamine

- ACh

- Dopamine

- Catecholamines

- 5-hydroxytryptamine

- Substance P

- Enkephalins

- NK1 receptor agonists

Anti-emetic agents

Anti-emetic agents can be used to treat motion sickness and to treat or prevent vomiting. They include the following;

- Dopamine (D2) receptor antagonists

- 5-hydroxytryptamine antagonists

- NK1 receptor antagonists

- Muscarinic receptor antagonists

- Histamine (H1) receptor antagonists

- Gastroprotective agents