Hyperparathyroidism

Also Known As – Parathyroid hyperplasia – Parathyroid adenoma - Fibrous Osteodystrophy – Grain Overload – Bran Disease – Big Head Disease – Millers Disease - Rubber Jaw – Metabolic Bone Disease

Introduction

Hyperparathyroidism is an endocrine disease caused by overactivity of the parathyroid gland and consequent raised body levels of parathyroid hormone (PTH). It occurs in many veterinary species and can be primary or secondary.

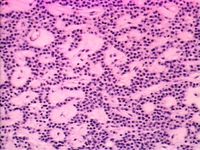

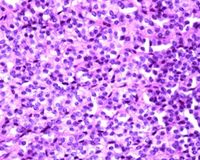

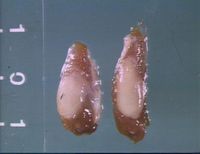

Primary hyperparathyroidism originates within the parathyroid gland itself and can be due to glandular hyperplasia or neoplasia. It is most commonly due to a solitary benign adenoma of either the internal or external parathyroid gland.[1]

Secondary hyperparathyroidism can be either renal or nutritional in origin:

Secondary renal hyperparathyroidism is a complication of chronic renal failure. This is due to hyperphosphataemia developing as a result of impaired glomerular filtration rate. Renal production of calcitriol is also reduced, exacerbating the resulting hypercalcaemia.

Secondary nutritional hyperparathyroidism is caused by excessive phosphorus intake causing a total or relative calcium deficiency by binding calcium in the gut and decreasing its absorption. This category encompasses bran disease in horses and also metabolic bone disease in reptiles.

Signalment

Primary hyperparathyroidism is seen infrequently in dogs and cats, but is documented in German Shepherd Dogs.

Secondary renal hyperparathyroidism is seen frequently in dogs and occasionally in cats.

Nutritional secondary HPT can affect horses of all breeds and ages that are either supplemented with large amounts of grain based concentrates or bran, or those that escape and break into a grain store or similar. It is also seen occasionally in dogs and cats fed all meat diets and pigs fed unsupplemented cereal feed. It is most commonly seen in young growing animals.

Metabolic Bone Disease occurs in a wide range of captive reptiles, particularly young green iguanas. It is also seen in some small mammals, e.g. chinchillas and degus.

Any disease in ruminants is very rare and usually mild.

Clinical Signs

The main effect of hyperparathyroidism is hypercalcaemia which causes a range of clinical signs. Polydipsia, polyuria, anorexia, lethargy and depression are the most common signs but animals may also be constipated, weak, stiff-gaited, shivering and vomiting. Mild hypercalcaemia may not generate any overt clinical signs.

Sequelae of hyperparathyroidism include fibrous osteodystrophy and organ failure due to metastatic calcification.

Osteodystrophy is the osteoclastic resorption of bone and replacement by weaker fibrous tissue. When this occurs in the long bones it causes shifting lameness and weakened bones that are prone to fracture. Compression fractures may also occur spontaneously and if this occurs in the vertebrae, nerve dysfunction results.[2] Weakened bones may also cause tendon and ligament avulsions.

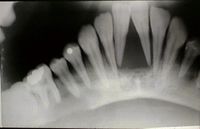

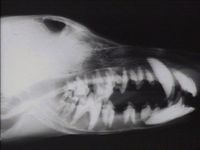

Fibrous osteodystrophy in the flat bones of the skull and face causes facial hyperostosis. This is seen in Bran disease or grain overload in horses and also in dogs with primary hyperparathyroidism. The face and head become grossly disfigured by excessive amounts of fibrous tissue laid down in an attempt to consolidate the weakened lamellar bone. In advanced cases, the mandible may become pliant and teeth may loosen, hence the colloquial name, “rubber jaw”. This may interfere with mastication and cause pain, dysphagia and consequent weight loss.

Grain overload is also an important cause of severe colic in horses. The sudden increase in fermentation results in enodtoxaemia and acidosis which can be fatal.

Animals affected by secondary renal HPT may exhibit classical signs of renal insufficiency such as polydipsia, polyuria, weight loss, vomiting and dehydration.

Metabolic Bone Disease in reptiles is caused by inadequate UVB light which diminishes Vitamin D production in the skin. In small mammals it is usually a straightforward dietary deficiency. Affected animals often have limb deformities, pathological fractures, are lethargic, very weak and inappetant and may also show signs of concurrent hypocalcaemia. They may also exhibit dysecdysis. Rodents may have loose or deformed teeth and faces.

Diagnosis

Electrolyte imbalances on blood biochemistry profiles are highly suggestive. Hypercalcaemia with a normal to low serum phosphorus and a low urine specific gravity are fairly consistent findings.

Urinary excretion of phosphorus and sometimes also calcium is increased. This can result in urolithiasis in some cases.

Serum PTH levels may be useful in diagnosing primary hyperparathyroidism, but only in animals with normal renal function, i.e., those with normal creatinine and blood urea nitrogen. A high PTH assay along with high creatinine and blood urea nitrogen is indicative of possible renal secondary HPT.

Exploratory surgery of the cervical region may identify enlarged parathyroid glands if no other test is available or confirmatory.

In cases of nutritional hyperparathyroidism, serum calcium is normal or low compared to high in other pathogeneses. Urinary excretion of phosphorus is markedly increased and serum PTH high. Radiographs will identify bony resorption and pathological fractures with fibrous tissue calluses.

MBD is usually identified by clinical signs and radiographic evidence of a poorly mineralised skeleton.

Treatment

Treatment for primary hyperparathyroidism usually required surgical excision. Hypocalcaemia is a known post-operative complication and supplementation may be required in the short or long term management. If the hypercalcaemia persists, metastatic disease should be suspected and investigated.

Renal secondary HPT therapy is directed at control of the renal disease by way of specialised diet and rehydration along with supplementation of calcitriol and phosphorus binders.

Horses with bran disease should be confined until radiographs show normal bone density. Diet should be rectified if inadequate, and calcium: phosphorus ratio maintained at 1:1-3:1 for the first 2-3 months followed by a normal ration. If horses have also been feeding on plants high in oxalates (which can also bind calcium in the intestine) then these should be removed from the diet and limestone can be added to the diet to prevent or treat any associating signs.

Horses with colic as a result of grain engorgement require aggressive fluid therapy and analgesia, and a nasogastric tube should be passed to alleviate any reflux. Measures should also be taken to try and prevent laninitis such as specialised shoes.

| Hyperparathyroidism Learning Resources | |

|---|---|

Test your knowledge using flashcard type questions |

Hyperparathyroidism Flashcards |

References

- ↑ Merck Veterinary Manual, Primary Hyperparathyroidism, accessed online 25/07/2011 at http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/40407.htm

- ↑ Merck Veterinary Manual, Metabolic Osteodystrophies: Fibrous Osteodystrophy: Primary Hyperparathyroidism, accessed online 25/07/2011 at http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/90313.htm

Lavoie, J-P., Hinchcliff, K. W (2008) Blackwell’s Five-Minute Veterinary Consult: Equine 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, pp524-525.

Merck Vet Manual, Renal Secondary Hyperparathyroidism, accessed 25/07/2011 at http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/90314.htm

Merck Vet Manual, Nutritional Diseases, accessed 25/07/2011 at http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/182606.htm&word=nutritional%2csecondary