Oesophageal Foreign Body

Introduction

Although many foreign objects are regurgitated from or transported through the gastrointestinal tract, those that are too large or have sharp points may remain lodged in the oesophagus and cause mechanical obstructions. Foreign bodies that become lodged in the oesophagus often have sharp points and include bones, fish hooks, needles, sticks and toys. The most common foreign bodies found in dogs are bones and bone fragments, particularly pieces of lamb vertebrae. In cats, toys are the most common objects to become lodged.

Obstructions occur most commonly at natural areas of narrowing along the oesophagus, particularly the thoracic inlet, heart base and distal high pressure zone, just oral to the the lower oesophageal sphincter.

The severity of oesophageal damage is dependent on the size and angularity of the foreign body, as well as the duration of obstruction. Even if the object is dislodged, there is a risk that residual inflammation may lead to the formation of strictures at the site of obstruction. In severe cases, the oesophagus may rupture into the mediastinum causing mediastinitis and possibly tension pneumothorax. Sharp objects (such as fish hooks) which lodge over the heart base may occasionally lacerate the great vessels passing from the heart and cause fatal internal haemorrhage.

Signalment

Although any age group may be affected, young dogs of the small terrier breeds are over-represented. It has been suggested that certain breeds (particularly the Border Terrier) may have delayed maturation of the systems that control oesophageal motility, increasing their risk of developing oesophageal foreign bodies in the first year of life.

Diagnosis

Clinical Signs

Animals may have a history of ingestion of bones or other objects. Typical signs include

- Acute onset of regurgitation or retching with hypersalivation/ptyalism.

- Animals may be unable to swallow (dysphagia) or may show pain on swallowing (odynophagia).

- If the object has lodged in the cervical oesophagus, a mass may be palpable over the left ventral neck.

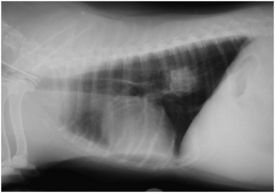

Diagnostic Imaging

Plain radiographs of the chest may reveal oesophageal foreign bodies if they are sufficiently radiodense. Poultry bones or other, more radiolucent, items may be more difficult to visualise. Signs of oesophageal perforation may be evident and it is important to assess these carefully. They may include:

- Pneumothorax, including tension pneumothorax in which the contents of the mediastinum will be pushed to one side of the chest. Air may also be observed in the retroperitoneal space if it escapes between the crura of the diaphragm.

- Pleural effusion, which may indicate a developing pyothorax.

- Pneumomediastinum or presence of fluid in the mediastinum.

Contrast radiography is rarely necessary but may be used to identify radiolucent foreign objects. Contrast agents must be used with caution if there is suspicion of oesophageal perforation.

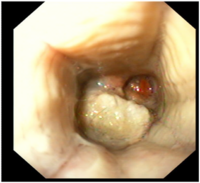

Oesophagoscopy can be used to provide a definitive diagnosis of an oesophageal foreign body.

Treatment

Surgical Removal

Oesophageal foreign bodies should be removed promptly to reduce the extent of mucosal damage, ulceration, perforation and subsequent stricture formation.

Endoscopic removal with grasping forceps is the method of choice for removing foreign bodies unless the object is too firmly lodged to pull free or radiographs of the chest suggest that the oesophagus has been perforated. If the object is too large to be safely removed through the mouth, it may be possible to push it into the stomach and remove it surgically via a gastrotomy.

If endoscopic removal is not possible, the foreign must be removed surgically. The approach used depends on the exact location of the object. In the cervical oesophagus, a ventral midline cervical approach is made and the trachea is retracted to the right to expose the oesophagus but in the thoracic oesophagus, a lateral (intercostal) thoracotomy or median sternotomy is performed. As the chest cavity is entered in either approach, the patient must be ventilated. In the abdominal oesophagus, a ventral midline coeliotomy is performed. The affected portion of the oesophagus is isolated with loops of umbilical tape and packed off from the thorax with moist laparotomy swabs. A longitudinal incision is made (to reduce the likelihood of subsequent stricture formation) and the foreign body is removed. The incision can then be closed with simple appositional sutures which must include the submucosa (the holding layer throughout the gastro-intestinal tract).

Post-operative Care

Aggressive medical treatment should be initiated after surgical removal to reduce the likelihood of stricture formation. This should include:

- Withdrawal of oral food for 2-3 days as standard but, if the inflammation is severe or rupture has occurred, a gastrostomy tube may be required.

- Oral sucralfate suspension is thought to bind to the base of any ulcers, to stimulate epithelial repair and to neutralise any refluxed gastric juices.

- Gastric acid secretory inhibitors (e.g. ranitidine, omeprazole) can be useful in cases of gastro-oesophageal reflux.

- Metaclopramide, a promotility drug that increases the tone of the lower oesophageal sphincter, may also be used to manage gastro-oesophageal reflux but not if oesophageal motility is thought to be impaired (i.e., if megaoesophagus is present).

- Broad spectrum intra-venous bactericidal antibiotics may be required in animals with severe oesophagitis or mediastinitis.

- Analgesia should be provided to encourage animals to eat after 2-3 days.

- Anti-inflammatory doses of corticosteroids (such as prednisolone) may be used to prevent fibrosis and further stricture formation in acute injuries but caution should be exercised if the animal has concurrent aspiration pneumonia.

Further procedures are also indicated to ensure that the surgery has not caused further damage. Radiographs of the chest should be obtained immediately after surgery to check that pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum have not developed and oesophagoscopy should be performed 2-3 weeks after the surgery to ensure that strictures have not developed at the site of the obstruction.

Prognosis

Animals with oesophageal foreign bodies without perforation carry a good prognosis. Those with oesophageal perforation carry a guarded prognosis depending on the degree of thoracic contamination. Surgical removal of foreign bodies is associated with more adverse effects than endoscopic removal.

| Oesophageal Foreign Body Learning Resources | |

|---|---|

To reach the Vetstream content, please select |

Canis, Felis, Lapis or Equis |

Search for recent publications via CAB Abstract (CABI log in required) |

Oesophageal Foreign Body publications |

References

- Hall, E.J, Simpson, J.W. and Williams, D.A. (2005) BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Gastroenterology (2nd Edition) BSAVA

- Merck & Co (2008) The Merck Veterinary ManualMerial

- Nelson, R.W. and Couto, C.G. (2009) Small Animal Internal Medicine (Fourth Edition) Mosby Elsevier.

| This article has been peer reviewed but is awaiting expert review. If you would like to help with this, please see more information about expert reviewing. |

Error in widget FBRecommend: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt698765d924b109_72498222 Error in widget google+: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt698765d92ce248_04542120 Error in widget TwitterTweet: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt698765d935a983_41508806

|

| WikiVet® Introduction - Help WikiVet - Report a Problem |