Dictyocaulus viviparus

| Dictyocaulus viviparus | |

|---|---|

| Class | Secernentea |

| Order | Strongylida |

| Super-family | Trichostrongyloidea |

| Family | Dictyocaulidae |

| Genus | Dictyocaulus |

| Species | D. viviparus |

Also known as: Bovine lungworm — Husk — Hoose — Dictyocaulosis — Parasitic Bronchitis

Introduction

Dictyocaulus viviparus is a bovine lungworm (a member of the Trichostrongyloidea). They are found in the trachea and larger bronchi and are responsible for parasitic bronchitis. There has been an increase in the incidence of husk in recent years; first season calves are particularly affected, although yearling and adult cattle may also succumb to the disease. Lungworm is responsible for reduced weight-gain and deaths in calves and yearlings and lowered milk-yield in dairy cows. A closely-related species is also responsible for one of the most important diseases of farmed deer. The parasite is of welfare importance if clinically affected animals are left untreated.

Hosts

Cattle, buffalo, deer and camels.

Identification

The adults are white thread-like worms, often less than 8cm in length.

Life Cycle

The adult worms are found in the trachea and the bronchi. The female lays embryonated eggs, which are later coughed up and swallowed. The eggs hatch during the passage through the intestinal system. First stage larvae are passed in the faeces of the host. Development into L2, and later L3, occurs within the faeces on the pasture.

A new host is infected by ingestion of infective larvae whilst grazing. These infective larvae are passed through the alimentary tract, where they penetrate the wall of the intestine. The larvae then migrate to the lungs, via the lymphatic system, or the blood circulation. These ascend the respiratory tree, where they mature into adult lungworms.

The prepatent period is 3.5 weeks.

Epidemiology

Our knowledge of the epidemiology of disease is far from complete, i.e. there are still outbreaks of parasitic bronchitis that we are unable to explain.

Disease is carried on from one year to the next by low numbers of L3 overwintering on pasture and from carrier animals (30% yearlings and 5% cows in an endemic area). The sequence of events that leads up to an outbreak of clinical disease are: a few calves in a group pick up overwintered L3 from pasture after turnout, leading to patent infections; the L1 develop to L3 in a dungpat. Then translation of L3 onto the pasture, which is largely by fungus (Pilobilus species) occurs. The remainder of calves are then infected. The infection may cycle 1, 2 or more times before sufficient L3 accumulate on pasture to cause disease (July – September). A large proportion of ingested larvae become inhibited in lungs of calves over winter, leading to pasture contamination following spring turnout, i.e. “carrier animals”.

Immunity is rapidly acquired following heavy exposure to infection (within a few weeks). There is minimal age resistance with older stock being susceptible if not previously exposed.

The primary infection has a penetration period of one week. Here, the larvae migrate to the lungs and there are no clinical signs. The prepatent period is then one to three weeks and involves the development and migration of larvae. This lead to bronchiolitis, which produces an eosinophilic exudate. This blocks the passage of air leading to alveolar collapse distal to blockage. The Patent Phase (weeks 4-8), is when the worms mature and become egg-producing. The main lesions are bronchitis (due to adult worms) and parasitic pneumonia (due to aspiration of eggs and larvae → cellular infiltration of polymorphs, macrophages and “foreign body” giant cells). The Postpatent Phase (weeks 8-12) is the period at the end of disease when the majority of worms are expelled. In 25% of cases, clinical signs flare up as a result of alveolar epithelialisation, which may be accompanied by interstitial emphysema and pulmonary oedema, or secondary bacterial infection.

Reinfection Syndrome occurs in immune cattle. They will only show clinical signs if exposed to a massive challenge; large numbers of larvae reach bronchioles and are killed by immune response.

Signalment

The disease affects cattle. It is more severe in calves and can even cause death in these species. There are milder clinical signs in adult cattle. There are no sex or breed predilections to the disease.

Clinical Signs

Signs include coughing and tachypnoea (depending on the number of worms) and an increased respiratory rate. In calves it can cause weight loss and even death in severe cases. In adult cattle, infection will tend to cause reduced milk yields and mild respiratory signs.

The penetration phase lasts one week and occurs when the larvae migrate to lungs. There are no clinical signs.

Then the prepatent phase lasts 1 - 3 weeks and is the development and migration of larvae leading to bronchiolitis and then eosinophilic exudate, causing the air passage to be blocked, resulting in alveolar collapse (distal to blockage). This is when clinical signs such as tachypnoea and coughing being to arise.

The patent phase then lasts around 4 - 8 weeks and the mature worms produce eggs during this period. Signs of bronchitis are seen due to mature worms and parasitic pneumonia is seen due to aspiration of eggs and larvae causing cellular infiltration of neutrophils, macrophages and giant cells.

Finally, the postpatent phase, which lasts around 8 - 12 weeks is seen and here, the majority of worms are expelled. In 25% of cases clinical signs may reappear as a result of alveolar epithelialisation, which may occur together with interstitial emphysema and pulmonary oedema, or secondary bacterial infection.

Reinfection syndrome may occur if immune cattle are exposed to large numbers; only then will they show clinical signs.

Diagnosis

Calves

Diagnosis is based on the seasonal incidence, previous grazing history and clinical signs. Definitive diagnosis can be gained by performing a Baerman technique on a faecal sample to identify larvae. Samples need to be taken from both healthy and sick cattle as carrier animals may be important in the epidemiology of disease, e.g. in an endemic area 30% yearlings and 5% cows harbour patent infections, as do vaccinated animals. NOTE: All lungworm-positive faecal samples are potentially significant.

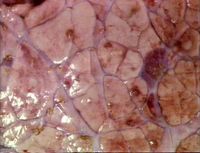

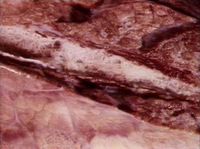

Post mortem examination can also be diagnostic; recovery of worms from lungs by the “Inderbitzen” or lung perfusion technique. Worms are flushed out of lungs by pumping water through pulmonary arteries. Water and worms passed out of trachea collected over sieve. NOTE: Only 200-300 worms are required to cause clinical disease c.f. >40,000 Ostertagia. Upon post mortem, one may also see pulmonary oedema and emphysema, which is thought to be caused due to a hypersensitivity response to a massive invasion of lungworm larvae.

Adult Cattle

Diagnosis is again based on seasonal incidence, previous grazing history and clinical signs. Definitive diagnosis can be achieved by faecal examination using the Baerman technique to identiy larvae. Both healthy and sick cattle should be examined. Blood and Milk examination (ELISA) to look for antibodies can be used, but this has variable results (depending upon Ag used). Herd results are better than individual results in this case.

Grass examination for larvae around dung pats is useful. Response to anthelmintic treatment will provide a retrospective diagnosis.

Treatment and Control

If the animal is clinically affected, treatment with anthelmintic such as ivermectin can be used.

Vaccination – “Huskvac” (Intervet, original vaccine = “Dictol”)

Should be given to first-season calves, > 2months old, reared indoors. It is an attenuated oral vaccine (each dose, 1,000 X-irradiated Dictyocaulus viviparus L3). Vaccination is required at 6 weeks and again at 2 weeks pre-turnout. NOTE: Never mix vaccinated and non-vaccinated animals. The vaccine is effective at preventing disease, although not 100% effective at preventing infection, i.e. even vaccinated calves may pass a few larvae → boost immunity in vaccinated calves, but could cause disease in non-vaccinated animals. A breakdown in protection can occur due to overwhelming challenge, improper storage or administration of vaccine, concurrent disease and mixing vaccinated and non-vaccinated calves. Therefore other control measures such as trying to keep a clean pasture and following instructions are very important.

Strategic anthelmintic programmes for preventing parasitic bronchitis can also be used. This will entail Ivermectin being administered at 3, 8 and 13 weeks post-turnout. NOTE: Residual activity of 28 days against lungworm. There will be no anthelmintic cover if challenge encountered either early (0-3 weeks) or late (after 17 weeks) in the grazing season.

| Dictyocaulus viviparus Learning Resources | |

|---|---|

Test your knowledge using flashcard type questions |

Cattle_Nematode Flashcards |

Search for recent publications via CAB Abstract (CABI log in required) |

Dictyocaulus viviparus publications |

References

Andrews, A.H, Blowey, R.W, Boyd, H and Eddy, R.G. (2004) Bovine Medicine (Second edition), Blackwell Publishing

Blood, D.C. and Studdert, V. P. (1999) Saunders Comprehensive Veterinary Dictionary (2nd Edition) Elsevier Science

Divers, T.J. and Peek, S.F. (2008) Rebhun's diseases of dairy cattle Elsevier Health Scieneces

Fox, M and Jacobs, D. (2007) Parasitology Study Guide Part 2: Helminths, Royal Veterinary College

Merck & Co (2008) The Merck Veterinary Manual (Eighth Edition) Merial

Radostits, O.M, Arundel, J.H, and Gay, C.C. (2000) Veterinary Medicine: a textbook of the diseases of cattle, sheep, pigs, goats and horses, Elsevier Health Sciences

| This article has been peer reviewed but is awaiting expert review. If you would like to help with this, please see more information about expert reviewing. |

Webinars

Failed to load RSS feed from https://www.thewebinarvet.com/respiratory/webinars/feed: Error parsing XML for RSS