Hypothyroidism

Also known as: Lymphocytic Thyroiditis — Cretinism

Introduction

Hypothyroidism refers to an inability to produce, release or respond to the thyroid hormones, tri- and tetra-iodothyronine (T3 and T4). T3 and T4 are produced in the thyroid glands under stimulation from TSH (Thyroid Stimulating Hormone) which is released from the thyrotroph cells of the anterior pituitary gland. The release of TSH is itself under the control of TRH (Thyroid Releasing Hormone), a tripeptide produced in parvocellular neurones of the hypothalamus. The cells of the thyroid glands produce the large protein thyroglobulin and store this in follicles. Thyroglobulin is iodinated and cleaved to release mainly T4 into the circulation. T3, which has a much greater activity than T4, is formed by the deiodination of T4 in peripheral tissues such as the liver, kidney and adipose tissues. Interruptions at any stage in this process may result in clinical hypothyroidism.

The thyroid hormones exert a major influence on body metabolism, controlling the basal metabolic rate (BMR) and the mobilisation of stored substrates. The hormones are also essential for normal growth and development and to enable the normal cycling of the hair follicles.

In conditions that cause great metabolic stress (such as severe illness), the BMR is reduced, the production of T4 is reduced and a proportion of the released T4 is converted to the inactive molecule reverse T3 (rT3). This results in a reversible depression of thyroid function known as euthyroid sick syndrome which may be differentiated from true hypothyroidism by the fact that TSH remains at a normal concentration. This is thought to have a protective function to preserve calories in catabolic states.

The majority of cases of hypothyroidism occur due to the destruction of the thyroid glands by a type IV autoimmune response, a process known as lymphocytic thyroiditis because this type of response is mediated by T cells. This autoimmune response develops spontaneously in most affected animals and usually progresses through a sequence of thyroiditis to necrosis and atrophy. In some cases, the administration of sulphonamide antibiotics may induce a reversible form of lymphocytic thyroiditis. Lymphocytic thyroiditis may occur concurrently with other immune-mediated endocrine diseases such as lymphocytic parathyroiditis or Addison's disease producing autoimmune polyglandular syndromes.

Hypothyroidism is the most commonly described endocrine disease of the dog but this may reflect overdiagnosis of the disease since animals with many different diseases will respond to thyroid supplementation. he possible causes of hypothyroidism include:

Primary hypothyroidism (involving the thyroid glands):

- Congenital failure to produce T4 and T3 is known as Cretinism and it is rare.

- Acquired hypothyyroidism may occur due to lymphocytic thyroiditis or other insults to the glands, including neoplasia. This form represents 90% of clinical cases.

Secondary hypothyroidism (involving the pituitary gland) represents 10% of clinical cases.

Tertiary hypothyroidism (involving the hypothalamus) is rare.

Peripheral hypothyroidism may occur due to a failure to convert T4 to T3 or due to tissue resistance to the thyroid hormones. Both forms are very rare.

Iodine deficiency is a rare form of hypothyroidism which is described most commonly in lambs born to ewes grazed on deficient soils or on goitrogenic brassica crops such as rape and kale.

In horses, the cause of hypothyroidism is usually unknown. Factors known to cause a decrease in thyroid hormone serum levels include: administration of phenylbutazone, sulphonamides, ingestion of high-energy or protein diets, ingestion of endophyte-infected fescue, training, old age. Cold weather can lead to increased levels of thyroid hormones,as can pregnancy.

Signalment

The disease is most common in dog of the larger breeds (including Golden Retrievers, Dobermanns, Giant Schnauzers and Scottish Deerhounds) and affected animals usually present during or before middle age.

The disease also occurs in adult horses and foals.

Diagnosis

It is likely that hypothyroidism is overdiagnosed in practice because it is associated with many non-specific clinical signs and because T4 levels are subject to fluctuations depending on concurrent drug therapy and illness. Many animals will respond to thyroid supplementation but this cannot be used to confirm a diagnosis.

Clinical Signs

Hypothyroidism is commonly associated with:

- Lethargy and exercise intolerance

- Obesity with a normal appetite

- Intolerance to cold

- Bradycardia (and reduced amplitude of QRS complexes on electrocardiogram)

- Bilaterally symmetric, non-pruritic alopecia which may progress to involve comedone formation and the development of pyoderma and seborrhoea. The skin may feel thickened and it may become hyperpigmented.

- Hypothyroidism is controversially associated with certain neurological signs, including facial palsy, laryngeal paralysis and a plantigrade stance.

- Abnormal oestrus cycle and reduced libido

- Sudden onset of uncharacteristic bouts of aggression in dogs

Cretins may be recognised as disproportionate dwarfs with a broad skull, a short mandible, short and thickened legs and an ataxic gait. These signs occur because thyroid hormones are needed for normal osteogenesis and endochondral ossification. Affected animals should be differentiated from proportionate dwarfs suffering from congenital panhypopituitarism or other causes of stunting.

Myxoedema refers to the deposition of mucinous material in the dermis of the skin. This unusual form of hypothyroidism may result in thickened areas of skin, a tragic facial expression and it may be associated with depression producing a myxoedematous coma.

Lambs born to ewes deficient in iodine during the last trimester of pregnancy may appear weak with poor fleeces and are at greater risk of neonatal mortality.

In foals, clinical signs include: prematurity, poorly ossified or malformed carpal and tarsal bones, forelimb contracture, ruptured common digital extensor tendon, mandibular prognathism and angular limb deformities.

In adult horses, signs include: myxoedema, dullness, bradycardia, agalactia, exercise intolerance, variable appetite, myopathies and alopecia.

Laboratory Tests

Animals with hypothyroidism often suffer from a mild non-regenerative anaemia. Biochemical analysis of a blood sample may also reveal hypercholesterolaemia and hypertriglyceridaemia as hypothyroid animals have reduced activity of the enzyme lipoprotein lipase which usually acts to facilitate the uptake of lipid from low and high density lipoproteins (LDLs and HDLs) into adipose tissue.

Other Tests

Several specific laboratory tests are available for the diagnosis of hypothyroidism but care should be taken to understand the limitations of each test. In many cases, two or more tests can be combined to increase sensitivity or specificity. The following tests may be considered:

- Measurement of T4 is the most commonly used test in general practice and it is widely available in the UK. A level of T4 which is below the lower reference limit is supportive of a diagnosis of hypothyroidism but this may also occur with non-thyroidal illnesses (producing euthyroid sick syndrome) and with some pharmaceutical products. T4 measurements are therefore not reliable in animals which are evidently ill.

- Measurement of TSH, when combined with T4, can be used to give a more complete picture of the nature of thyroidal disease. Most animals with hypothyroidism will have a raised TSH (as negative feedback exerted by the thyroid hormones on the anterior pituitary gland is reduced) whereas those with euthyroid sick syndrome will usually have a normal level of TSH.

- Measurement of free T4 can also be used to try to differentiate euthyroid sick syndrome from true hypothyroidism. Free T4 refers to the T4 which is not bound to plasma proteins and is therefore active in the blood. The level of free T4 will be reduced in cases of true hypothyroidism but it remains in cases of euthyroid sick syndrome even though total T4 will be reduced.

- The TSH stimulation test was used previously to diagnose hypothyroidism. This involved measuring baseline T4, injected bovine TSH and measuring T4 again after 4 hours. In dogs with normal thyroid function, the second T4 measurement would be expected to be at least double that of the first sample. The test is not currently in use because the bovine TSH is no longer available.

- In more complex cases, it is possible to measure T3, free T3, reverse T3 and perform a TRH stimulation test.

Pathology

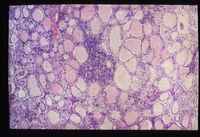

Lymphocytic thyroiditis is associated with an infiltrate of lymphocytes and it may involve fibrous replacement of thyroid tissue progressing to complete destruction. Clinical signs are not seen until 75% of the functional tissue of the thyroid is lost.

The disease has a similar pathogenesis to Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in humans.

Thyroid carcinomas may also be a cause of hypothyroidism in dogs and these tumours may metastasise widely to the lungs, local lymph nodes and along the oesophagus.

Animals with iodine deficiency (including lambs born to deficient ewes) may develop diffuse parenchymatous goitres as thyroglobulin continues to accumulate in the gland but is not cleaved and released into the circulation. A diagnosis of iodine deficiency can be made in neonatal lambs if the thyroid gland weighs more than 2 grams.

Treatment

In dogs and horses, deficient thyroid hormones can be replaced with synthetic products. Most affected animals receive L-thyroxine (T4) in tablet form and this has the advantage that the replacement hormones are still subject to the peripheral regulatory mechanisms which control the conversion of T4 to T3. The effects of alterations in the thyroid hormones take a long time to become apparent and improvements in some clinical signs may not therefore be observed until after 2-3 months of therapy has been completed.

Synthetic T3 is available but this requires more frequent dosing and is more expensive than the T4 substitutes. It does act faster than L-thyroxine and it may be useful in cases of myxoedematous coma which require urgent treatment.

Hypothyroid animals which receive replacement therapy should be presented to their veterinary surgeon regularly for serial measurements of T4 to ensure that the level of supplementation is appropriate to the individual animal.

Prognosis

The prognosis for long-term management is good if the diagnosis has been made using reliable methods. It may take some time for clinical signs to improve and to titrate the dose of replacement hormone to an appropriate level.

Also see Hypothyroidism in Reptiles

| Hypothyroidism Learning Resources | |

|---|---|

Test your knowledge using flashcard type questions |

Equine Internal Medicine Q&A 21 Small Animal Dermatology Q&A 22 Small Animal Abdominal and Metabolic Disorders Q&A 17 |

Search for recent publications via CAB Abstract (CABI log in required) |

Hypothyroidism publications |

References

Ettinger, S.J, Feldman, E.C. (2005) Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (6th edition, volume 2) Elsevier Saunders Company

Lavoie, J-P. (2009) Blackwell's Five-Minute Veterinary Consult: Equine John Wiley and Sons

Snyder, J. (2006) The Equine Manual Elsevier Health Sciences

| This article has been peer reviewed but is awaiting expert review. If you would like to help with this, please see more information about expert reviewing. |

Error in widget FBRecommend: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt69a005067af1f3_36247264 Error in widget google+: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt69a0050683bec7_47625936 Error in widget TwitterTweet: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt69a00506892f82_53288174

|

| WikiVet® Introduction - Help WikiVet - Report a Problem |