Reptile Cardiovascular Disease

Introduction

Cardiac disease is not a common finding in captive reptiles.

When cases are presented, it is important to characterise whether the cardiac disease is the primary cause of the illness or the secondary result of other systemic illness. It seems that the majority of the cases presented are secondary to systemic illness.

Primary disease may involve right AV valve insufficiency, which has been reported in one carpet python, resulting in congestive heart failure.

Due to the lack of septation in squamata and chelonia, elevated diastolic pressures could be shared across all ventricular compartments, resulting in bilateral heart failure.

Murmurs can occasionally be auscultated. Tachycardia has been observed with cardiac insufficiency, and cardiomegaly may be evident on physical examination.

Dilated cardiomyopathy has been anecdotally reported in snakes as spontaneous disease as well as following infection.

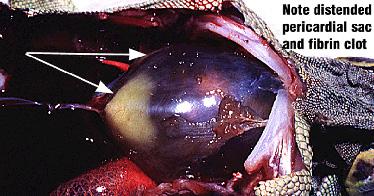

Aortic aneurism has been reported in a Burmese python; pericardial effusion of unknown etiology in a turtle; myocardial listeriosis in a bearded dragon; myocardial salmonellosis in a boa; cardiovascular spirorchid flukes can cause endocarditis, arteritis and thrombosis in green turtles.

The heart of most snakes is located at a point one-third to one-fourth of its length caudal to the head. In some aquatic species, the heart is located in a more cranial position. The chelonian heart is located on the ventral midline where the humeral, pectoral, and abdominal scutes of the plastron intersect. In most species of lizards, the heart is encased in the pectoral girdle. Varanidsare an exception, as their heart is located more caudally in the coelomic cavity.

Clinical Signs

Most of the signs are non-specific. Reptiles with cardiac disease may appear lethargic or depressed.

Normally active animals, such as tortoises, may appear exercise intolerant.

Reptiles are obligate nasal breathers, so a history of open mouth breathing also may be an indication of cardiac disease.

A detailed history is essential in highlighting these signs as well as any deficiencies in husbandry such as hypothermia or dehydration which may affect cardiac function.

The reptile heart should be assessed as part of a routine physical examination. There may be swelling in the area of the heart, peripheral edema, ascites, cyanosis, anorexia, weight loss, and sudden death.

In snakes, the size of the heart can be roughly estimated.

Heart contractions can be observed by movements of the ventral scutes.

Reptilian heart sounds are of very low amplitude and cannot be consistently ausculted using a standard stethoscope, so it is unusual to include a cardiac auscultation in the clinical examination.

When performing a physical examination on a reptile, it is important to consider the environmental temperature. If the reptile’s body temperature is less than optimal, the results of the examination may be misleading. For example, a reptile maintained at a low environmental temperature may appear bradycardic when the condition is actually a result of its response to the environment.

Diagnosis

As well as the physical examination, haematology and plasma biochemistry are important diagnostic tests that provide insight into the working physiology of the patient. Elevations in creatine kinase activity appear to be highly correlated to cardiac muscle in the green iguana. Alterations in aspartate aminotransferase may also occur with damage or injury to the cardiac muscle. Imbalances noted with electrolytes, enzymes, proteins, and minerals should be addressed when developing a treatment plan.

The ECG can be an invaluable tool for monitoring cardiac function in reptiles. Interpretation of the ECG may be difficult but may highlight some electrical conduction disturbances.

Radiography is another useful diagnostic test to evaluate heart size in snakes and crocodilians. Comparing radiographs of similar sized species may be useful when evaluating heart size in an abnormal case.

Doppler echocardiography can provide an accurate, noninvasive ante mortem diagnosis of cardiac disease in reptiles. Snake and lizard hearts can easily be identified using cardiac ultrasound. In snakes, the ultrasound probe should be placed on the ventral surface of the skin overlying the heart. In lizards, the probe can be placed in the axillary region and directed medially because the heart is located within the pectoral girdle. Echocardiography can provide important insight into cardiac motion and function, structural defects, heart valve motion, pericardial effusion, cardiomegaly, and intracardiac masses.

Treatment

Therapy of cardiac disease is virtually unreported.

Various diuretics have been used but the lack of appropriate receptors in the kidney is a potential problem.

Lizards

Cardiovascular disease may be primary or secondary.

Aetiology - it may be infectious, parasitic, congenital or nutritional (e.g. calcification of large vessels)

Clinical signs - Clinical signs of cardiovascular disease are usually non-specific such as anorexia and weight loss. Signs such as swelling in the area of the heart, peripheral oedema and ascites warrant investigation of the cardiovascular system.

Diagnosis

- History

- Physical examination, especially auscultation

- Blood culture

- Radiography

- Ultrasound

- Doppler flow detector

- Electrocardiography though interpretation may be a problem

- Necropsy

Treatment - Includes supportive treatment, antimicrobial if infectious, and correction of husbandry.

| Reptile Cardiovascular Disease Learning Resources | |

|---|---|

Test your knowledge using flashcard type questions |

Reptiles and Amphibians Q&A 22 |

Search for recent publications via CAB Abstract (CABI log in required) |

Lizard Cardiovascular Disease publications |

Full text articles available from CAB Abstract (CABI log in required) |

Approach to the exotic cardiology patient. Rishniw, M.; Australian Small Animal Veterinary Association, Bondi, Australia, 32nd World Small Animal Veterinary Association Congress, Sydney Convention Centre, Darling Harbour, Australia, 19-23 August 2007, 2007, pp unpaginated, 31 ref. - Full Text Article |

References

Frye, F. (1995) Self-assessment colour review of Reptiles and Amphibians Manson Publishing

Rishniw, M. (2007) Reptile Cardiology WSAVA Proceedings

Kik, M. (2005) Reptile Cardiology: A Review of Anatomy and Physiology, Diagnostic Approaches, and Clinical Disease Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine, Vol 14, No 1: pp 52– 60

| This article has been peer reviewed but is awaiting expert review. If you would like to help with this, please see more information about expert reviewing. |

Webinars

Failed to load RSS feed from https://www.thewebinarvet.com/cardiology/webinars/feed: Error parsing XML for RSS