Large Intestine Overview - Anatomy & Physiology

Introduction

The large intestine extends from the ileum of the small intestine to the anus. Water, electrolytes and nutrients are absorbed which concentrates the ingesta into faeces. Faeces are stored prior to defeacation. There is no secretion of enzymes and any digestion that takes place is carried out by microbes. All species have a large microbial population living in the large intestine, which is of particular importance to the hindgut fermenters. For this reason, hindgut fermenters have a more complex large intestine with highly specialised regions for fermentation.

Development

The caecum, ascending, and part of the transverse colon have already been considered in the development of the small intestine. The hindgut forms the portion of the transverse colon that lies to the left of the midline, the descending colon and cloaca. The anal membrane breaks down to allow communication with the exterior.

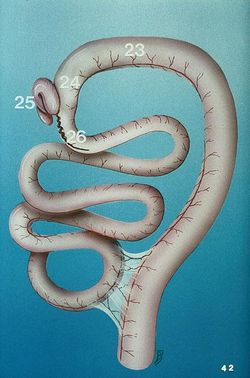

The large intestine can be divided into: The caecum, colon, rectum and anus.

Function

Water Absorption: Chyme entering the large intestine is semi solid. By the time chyme leaves the large intestine as faeces it is solid because most of the remaining water has been absorbed. Water absorption is achieved by the generation of an osmotic gradient between the gut lumen and the enterocytes. Sodium is actively transported into the enterocyte and is followed passively by chloride ions to increase the osmotic potential of the enterocyte.

Vitamin Absorption: The large intestine is colonised by a large quantity of bacteria that produce vitamins as a consequence of their own metabolism. The large intestine absorbs these vitamins, in addition to vitamins present in the diet.

Transportation: Chyme is transported slowly in the large intestine. Chyme from the small intestine passes into the caecum and the colon in similar amounts.

Storage and Defecation: Remaining water, waste and undigested food is stored as faeces prior to defecation. Defecation is the periodical expulsion of faeces into the environment.

Defence Against Pathogens:

Secretions

Mucus inhibits contact and protects the mucosal surface. Digestive enzymes nonspecifically target bacteria and viruses. Bile kills some bacteria and viruses.

Epithelium

"Tight junctions" between epithelial cells prevent entry of macromolecules and pathogens into the intestinal tract. Epithelial cells have a very high turnover rate, thus preventing pathogens with a longer life cycle from successfully colonising.

Commensal flora

Commensal flora competitively inhibit attachment of pathogens to enterocytes in addition to competing for nutrition and substrates. Many also produce inhibitory growth substances that are toxic to other bacteria (McGavin and Zachary, 2007).

Movement

Continuous peristalsis discourages persistence of toxins and aids in their elimination from the gut.

Cell-mediated and humoural defences

The lamina propria contains macrophages, B and T lymphocytes, plasma cells, and mast cells. Lymphoid aggregates known as Peyer's patches within the small intestine aid in immunity. Secretory IgA and IgM provide humoural immunity and help prevent attachment of pathogens to the intestinal epithelium. Lysozyme from Paneth cells inhibits bacterial growth (McGavin & Zachary, 2007).

Vasculature

The cranial mesenteric artery supplies the caecum, ascending, and part of the transverse colon. The caudal mersenteric artery supplies the rest of the transverse colon, the descending colon and the rectum.

Innervation

Similarly to the small intestine, there are pacemaker cells that generate an action potential. Cells are able to function as a syncytium due to gap junctions, allowing the action potential to spread. Contractions are generated in the forward (peristaltic) and backward (antiperistaltic) directions. Antiperistaltic contractions move ingesta into the caecum in some species. The formation of action potentials is under a much stronger neural influence than in the stomach and small intestine. The large intestine recieves sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation. The sympathetic have coeliac, cranial mesenteric and caudal mesenteric ganglia. As the sympathetic fibres leave the ganglia, they surround their respective artery. Parasympathetic innervation increases the frequency of action potentials and thus stimulates peristalsis. Sympathetic innervation has the opposite effect. Neurones interact with the myenteric plexus to affect contractility, and with the submucosal plexus to affect secretions. Motility of the large intestine increases during meals, possibly as a result of gastrin and cholecystokinin secretion.

Lymphatics

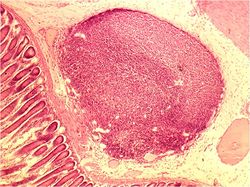

Lymphatic nodules are present in the mucosa of the large intestine. Lymph nodes of the large intestine drain into one of two centres, the cranial mesenteric centre or the caudal mesenteric centre. The cranial mesenteric centre includes lymph nodes of the small intestine and the following lymph nodes of the large intestine The caecal - drains the caecum. The Colic - drains the ascending and transverse colon. The efferent vessels of these lymph nodes converge to form the cranial mesenteric trunk which drains into the chyle cistern. The caudal mesenteric centre includes the lymph nodes of the descending colon, which are situated in the mesocolon. The efferent vessels of these lymph nodes converge to form the caudal mesenteric trunk which unites with the cranial mesenteric trunk to open into the chyle cistern.

Histology

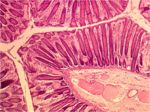

- The mucosa of the large intestine is smooth; there are no villi or microvilli.

- Mucosal glands are much longer and straighter.

- The number of goblet cells in the mucosa is increased compared to the small intestine.

- Mucus is very important for lubrication of the ingesta as it passes through the intestine, particularly as more water is absorbed from the lumen making chyme drier.

- There are numerous scattered lymph nodules.

- The number of lymph nodules increases compared to the small intestine.

- The submucosa is much reduced in thickness.

- Taenia may be present.

- These are concentrations of the longitudinal muscle layer into long bands.

- When the taenia contract, they cause shortening of the large intestine, which produces saccualtions, or haustra.

- Haustra help to mix the content and to slow the transit time

- Many glands are present in the mucosa and skin of the anal region.

Species Differences

Carnivore

Digestion is nearing completion by the time chyme enters the large intestine. The dog and cat posses two anal sacs.

Ruminant

Digestion is nearing completion by the time chyme enters the large intestine.

Equine

Most digestion occurs in the large intestine. Taenia are present.

Porcine

Taenia are present.

Links

Test yourself with the Large Intestine Flashcards

Click here for information on pathology of the Small and Large Intestine

Click here for information on Diarrhoea

Video links:

Pot 48 The Small and Large intestine of the Ruminant

Pot 52 Lateral view of the Abdomen of a young Ruminant

Left Sided topography of the Equine abdomen

Right sided topography of the Equine Abdomen

Small and Large intestine of the Sheep