Vaccines

Introduction

Why do we vaccinate animals?

- To protect against infectious diseases

- Where there is no effective treatment once infected E.g. FeLV, FIV

- Where disease is life-threatening E.g. Canine Parvovirus

- To prevent the spread of disease by virus excretion E.g. Rabies, FMDV

The goal is to vaccinate 90% of the population to reduce the amount of endemic virus until no new infections occur. Once the disease risk is low, vaccination can be replaced by an eradication or quarantine programme

How do vaccines work?

Vaccination induces an immunological memory of the infectious organism. High levels of cytotoxic T cells and neutralising antibody are activated 24 - 48 hours post vaccination as a secondary response (instead of 4-10 days later as a primary response). Neutralising antibody then blocks the attachment of the infectious organism to host cell receptors.

Endogenous vaccines cause antigens to be made as new proteins by the cell, bacterium or virus and involves MHC class I processing live virus, recombinant virus or DNA vaccines.

Exogenous vaccines are when the antigen is processed from the outside by endocytosis without any new proteins being made by the host cell. This involves MHC class II processing inactivated and subunit vaccines.

Route of Administration

- Usually by subcutaneous injection for systemic protection (IgG). Some vaccines such as the myxomatosis vaccine NobivacTM Myxo (Intervet UK Ltd) require an intradermal injection as part of the administration procedure.

- For a localised mucosal immune response, intranasal administration is required (IgA) e.g. kennel cough vaccine.

Vaccination Options

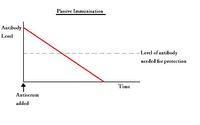

Passive immunisation

Advantages

- Immediate protection

Disadvantages:

- Short duration of action; temporary protection is obtained by the administration of preformed antibody from another individual of the same or of a different species. The acquired antibodies are used in combination with antigen, and catabolised by the body, meaning protection is gradually lost over time

- Injection of antiserum may cause an allergic response

- Antiserum contains many antibodies, not just the specific antibodies needed

Types of antibodies administered:

- Maternally-derived antibodies in colostrum when there is a failure of passive transfer of Immunoglobulin G

- Antiserum

- The antibodies are used in combination with Antigen Recognition|antigen (and often an adjuvant) which is injected into a host animal

- The immune system of that animal synthesises antibodies

- Repeated injections at intervals increases total antibody production

- The immunised animal is bled and the serum collected which contains the newly made antibodies. The serum is called antiserum.

- The serum can then be injected into a different animal to confer passive immunisation

- Example of when passive immunisation is used:

- Suspect tetanus

Passive Immunotherapy with Antibody

| INFECTION | HUMAN SOURCE OF ANTIBODY | EQUINE SOURCE OF ANTIBODY | USE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetanus Diptheria | Used | Used | Prophylaxis treatment |

| Botulism | Not used | Used | Treatment |

| Venomous bite | Not used | Used | Treatment |

| Rabies | Used | Not used | Post-exposure to virus |

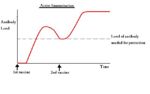

Active immunisation

- Administer antigen so the patient develops its own antibodies to protect against disease

- Living organisms

- Dead organisms

- Toxoids

- Subunit antigens

- DNA

Advantages

- Long duration of action

- Once antibody is produced against the antigen, memory cells are formed which continue circulating in the body

- For further information on memory cells click here

Disadvantages

- Delay in protection

- The host's immune system needs to evoke an immune response against the antigen which can take a few days

- For further information on the antibody response click Adaptive Immune System

- Often needs two or more doses

- The first dose initiates the priming reaction where antibody production ceases after a few weeks, but the second and subsequent doses create memory cells which remain in the circulation for a much longer period of time

- For further information on the T cell independent and dependent responses click here

What antigen(s) do we use in the vaccine?

Whole Organism

- Live attenuated organism

- Virulent organisms cannot be used as vaccines as they would cause disease

- Virulence is reduced by growing the organism in altered conditions (e.g. in cells or eggs), so that it is less able to replicate when introduced to the host, and therefore less likely to cause disease

- Produces a superior response to disease than using killed organisms as the dose of antigen is larger and more sustained

- Virulence can also be reduced by genetic engineering

- Naturally occurring avirulent strains can also be used

- Response takes place at the site of natural infection, producing a greater local response than with killed organism vaccines

- E.g. The current vaccine for Tuberculosis (called BCG) contains an attenuated form of a mycobacteria

- E.g. Vaccines for Leishmaniasis

- E.g. Vaccines for parainfluenza virus 3 of calves is developed to be temperature-sensitive so that it grows at 34 C in the upper respiratory tract but not at 38 C in the lungs

- Killed inactivated organism or toxin (toxoid)

- Virulent and toxic organisms cannot be used as vaccines as they would cause disease

- Organisms can be killed using radiation or chemicals so that they still possess the

antigens to stimulate an immune response, but the organisms are unable to replicate inside the host

- Toxins are inactivated to produce a toxoid which will still have the antigens needed to produce an immune response but will not be harmful to the host

- Needs two doses (for an explanation on the T cell response click here)

- 1:4000 formaldehyde is the current preparation

- Inactivants containing azuridines and beta propiolactone are being developed which do not leave a persistent infectious viral fraction (like formaldehyde)

Subunit Vaccine (part of the organism)

- Purified protein

- Single envelope protein separated from a purified virus by detergent then centrifuged (traditional method)

- Genetic engineering can now make single protein vaccines

- Recombinant or synthetic protein

- The gene for the antigen required is inserted into a virus vector or cloned into bacteria allowing endogenous expression

- Small antigens, such as peptides, can be synthetically produced

- E.g. Being developed constantly to fight the Influenza viruses

- E.g. Canary pox vaccines encoding rabies or FeLV spike proteins (canary pox is safe as it undergoes incomplete replication in mammalian skin cells)

- DNA coding for proteins (antigens)

- Circular DNA plasmids expanded in disabled E.coli strains and then purified

- Plasmids express the foreign gene insert at the site of injection

- Can be vaccinated directly into the host

Adjuvants

- Used with vaccines containing inactivated organisms which alone only stimulate a weak immune response

- Some create a depot of antigen at the injection site allowing a steady flow of antigen into the afferent lymph

- Some stimulate the immune system to amplify the adaptive immune response to antigens

- E.g. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)

- E.g. PAMP-like adjuvants which assist naive T cell priming

- Different subtypes of T helper cells are stimulated by different adjuvants

- E.g. Aluminium salts generate bias T helper II responses for antibody-mediated immunity

- E.g. Killed mycobacteria generate IL-12 producing good cell-mediated immunity

- Adjuvants decrease the number of injections needed and the amount of antigen administered

Marker Vaccines

- Distinguish infected from vaccinated animals

- Have a deleted protein or gene

- Vaccinated animals cannot make antibody to the missing protein whereas infected animals can

- Helps immunosurveillance for animals infected by a virus in countries that vaccinate against the virus

Which type of vaccine is used for each disease?

- The life-cycle of the organisms needs to be understood to ascertain the best type of immune response for fighting the particular infection

- A vaccine can be created to provide specific immunity which is best suited for fighting the specific infection

Immunity to Virus Infection

- The virus life cycle consists of an extracellular phase, a replicative intracellular phase and another extracellular phase spreading viral particles to other cells to begin the life cycle again

- Immunity for the extracellular phase requires neutralising antibody

- B cells needed

- T helper type II cells needed (for the MHC class II pathway)

- Live vaccine can be used

- Killed vaccine can be used

- Subunit vaccine can be used

- Immunity for the intracellular phase requires CD8+ cytotoxic T cells

- MHC class I pathway

- Only live vaccine can be used to get into cells (entering via the endogenous pathway)

Immunity to Bacterial Infection

- Extracellular bacterial infection needs antibody production for opsonisation and to activate the complement pathways

- B cells needed

- T helper type II cells needed

- Vesicular infections can only be cured by organisms being destroyed inside macrophages

- T helper type I cells needed

When do we vaccinate?

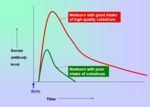

- Usually when animals are young

- Breeding females so immunity is passed to offspring via the colostrum

- Protects neonates for the first 8-12 weeks of life

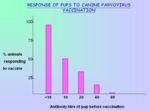

- Vaccination of young animals should be when the natural passive immunity decreases below the threshold for providing protection. Active immunity should then be stimulated so that the animal has constant protection. The vaccination should not be given too early, as the natural immunity can interfere with immunisation by binding and neutralising the vaccine antigens.

- 2 vaccines are usually given to allow for differences between neonates, as the point where natural immunity decreases and active immunity needs to be stimulated, will differ between littermates and between different animals

Dog Vaccinations

Diseases covered by Vaccination

- Canine Parvovirus

- Canine Distemper

- Canine Infectious Hepatitis

- Leptospirosis

- Canine Parainfluenza virus

- Kennel Cough

- Rabies

When to Vaccinate

- Puppies are usually first vaccinated between 6 to 8 weeks of age

- A second vaccination is needed 2 weeks later

- Adult dogs need booster vaccination regularly (depending on the specific vaccination)

Cat Vaccinations

Diseases covered by Vaccination

- Feline Infectious Enteritis (Feline Panleucopenia)

- Feline Infectious Respiratory Disease 'Cat Flu'

- Feline Herpesvirus

- Feline Calicivirus

- Feline Leukaemia virus

- Killed whole virus (only used in USA)

- Purified subunit

- Recombinant subunit

- Recombinant canarypox

- Feline Infectious Viraemia

- Killed whole virus containing A and D subtypes (only used in USA)

- Feline chlamydiosis

- Chlamydophila felis

When to Vaccinate

- Kittens are usually vaccinated around 9 weeks old

- A second vaccination is needed 3 weeks later

- Adult cats need booster vaccination regularly (depending on the specific vaccination)

Rabbit Vaccinations

Diseases covered by Vaccination

- Viral Haemorrhagic Disease

- Myxomatosis

When to Vaccinate

- Rabbits can be vaccinated against Myxomatosis from 6 weeks of age

- VHD from 2½ to 3 months of age

- Booster vaccinations are given every 12 months. In areas at high risk of myxomatosis, it is recommended to give myxomatosis boosters at six-monthly intervals.

Vaccine Failure

- Recipient is already infected with the virus or immunosuppressed

- Break down of the cold-chain during transport

- Improper administration

- Mixing of inactivated and live vaccines in the same syringe

- Recipient has maternal antibody to the vaccine

- Not enough animals vaccinated

- Boosters not done

- Vaccine is counterfeit or homeopathic

Test Yourself

Test yourself with the Vaccination Flashcards

Links

References

Textbooks

- Ivan Roitt: Essential Immunology, Ninth edition

Lecture Notes

- Dr Brian Catchpole BVetMed PhD MRCVS

- Dr Peter H Russell BVSc MSc PhD MRCVS FRCPath