Flea Allergic Dermatitis

Also known as: FAD — Flea Allergy Dermatitis — Flea Bite Hypersensitivity — FBH — Flea Dermatosis

Introduction

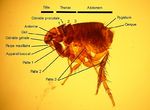

Flea allergic dermatitis is the most common skin disease of dogs and cats worldwide. Cases are caused by flea infestation, mainly by Ctenocephalides felis, the cat flea, but Ctenocephalides canis, Archaeopsylla erinacei, Spilopsyllus cuniculi and Pulex irritans can also be found on cats and dogs. Fleas are blood sucking, wingless insects that live and breed in the hair coat of an animal and often cause pruritus and annoyance. The term flea allergic dermatitis refers to the condition that arises due to hypersensitivity to flea saliva when a flea bites. This is initiated by a low molecular weight hapten and two high molecular weight allergens. Flea saliva also contains histamine-like compound that irritate the skin to cause flea bite hypersensitivity (type I and type IV).

Intermittent exposure to fleas and saliva is far more likely to result in flea allergic dermatitis than continued exposure. Both IgG and IgE antibodies have been implicated in the reaction, and both immediate and delayed hypersensitivity reactions are seen. Cutaneous basophil hypersensitivity also becomes established: basophils infiltrate the dermis under the influence of IgG or IgE and degranulate upon subsequent exposures to give further immediate and delayed hypersensitivity.

Signalment

Flea allergic dermatitis may be inherited in an unknown pattern. It is more common in atopic breeds, but any breed of dog or cat can be affected. Flea allergic dermatitis is uncommon in animals less than six months of age, and the average age range is 3-6 years. However, any age of animal can suffer flea allergic dermatitis. There is no sex predisposition.

Diagnosis

Clinical Signs

Animals typically present with a history of compulsive biting, chewing and licking. Cats may scratch around the head and neck. Signs of fleas and flea dirt may be seen on both dogs and cats.

Clinical exam findings depend on the severity of the hypersensitivity reaction and the degree of exposure to fleas. Fleas or flea dirt may be found, but these can be removed by overgrooming in particularly sensitive animals. In dogs, lesions are concentrated along the caudal dorsum, the caudal aspects of the thighs, the ventral abdomen and the cranial antebrachium, but any area may be affected. Within fifteen minutes of receiving a flea bite a papule appears and persists for up to 72 hours, when it forms a crust. However, these lesions may be difficult to appreciate due to the secondary changes that result from self-trauma in response to pruritus. These may include excoriations, erythema, seborrhoea, hyperpigmentation and lichenification or pyotraumatic folliculitis. A mild secondary bacterial folliculitis may also be present.

Cats respond to most cutaneous insults in one of four reactions patterns (miliary dermatitis, eosinophilic granuloma complex, head and neck pruritus, symmetrical alopecia). This is also true in flea infestation and flea allergic dermatitis. Miliary dermatitis is by far the most common presentation in this case, and is typically seen on the caudal dorsum and around the head and neck. Symmetrical alopecia of the inguinal region and the eosinophilic granuloma complex may also be seen.

Differential diagnoses for flea allergic dermatitis include other hypersensitivities, such as atopy or food allergy, and ectoparasites such as sarcoptic mange or cheyletiellosis. Primary keratinastion disorders should also be considered.

Additional Tests

Diagnosis is usually made based on clinical signs an history, but is supported by evidence of fleas or flea dirt. This can be difficult to find, particularly in cats, but placing combed material on moistened light-coloured paper can help demonstrate flea dirt. Intradermal testing with flea antigen will give an immediate hypersensitivity reaction in 90% of allergic animals, and a delayed reaction can be seen in some animals not showing an immediate response. However, the response to a flea control programme is normally sufficient to rule the diagnosis in or out.

Pathology

Grossly, papular dermatitis is seen in combination with any of crusting, erythema, alopecia, excoriations, hyperpigmentation or lichenification. Microscopically, flea allergic dermatitis presents as a hyperplastic superficial perivascular dermatitis. Oedema may be seen, together with an influx of mast cells, eosinophils, lymphocytes and histiocytes.

Treatment

Treatment of flea allergic dermatitis is by appropriate flea control.

To implement an effective flea control programme, it is important to understand the flea life cycle. After a flea takes a blood meal from a pet, mating and egg production occurs within two to three days. The small, white eggs produced are laid on the host but fall to the ground where they hatch to larvae. Insect development inhibitors may act on eggs for a period after laying, and insecticides can affect hatchability. Hatching normally occurs within three weeks of laying depending on environmental temperature and humidity. Flea larvae feed on the faeces of adult fleas, and undergo two moults before pupating. Generally, the pupal stage lasts around ten days, but it is possible for the pupa to survive for up to a year within its cocoon. This cocoon is resistant to parasitacidal agents, as well as dessication and freezing. Warmth, vibrations and carbon dioxide indicate the presence of a suitable host to the pupated flea, stimulating the emergence of the adult. The adult flea is then drawn to the host by heat and carbon dioxide, as well as the individual "attractiveness" of the host.

There are therefore two main aims of flea control:

- To kill adult fleas from the affected animal, and

- To eliminate the reservoir of eggs and immature fleas in the environment, thus preventing re-infestation.

Although flea repellents and mechanical methods of removing fleas are available, the most effective way to achieve flea control is by the use of chemicals that will kill adults, larvae or eggs. There are several products available to kill adult fleas on the host which are safe and effective. These include fipronil, imidacloprid and selemectin, which should be used on a regular basis in accordance with instructions in order to give ongoing control of adults. Choice of product may be influenced by route of administration, mechanism of action, duration of effects and efficacy.

There are two main groups of products that act on life stages free living in the environment. Juvenile hormone analogues, such as methoprene and pyriproxifen, disrupt the normal sequential activation of genes necessary to direct the development of successive stages of the flea life cycle. These products are also ovicidal. Insect development inhibitors, such as lufenuron and cyromazine, interfere with chitin synthesis. Lufenuron prevents the synthesis of chitin to interupt embryogenesis, hatching and moulting, whereas cryomazine stiffens chitin to prevent expansion with flea growth. Use of chemicals these chemicals in combination with those controlling the adult flea population on the host gives complete flea control.

If pruritus is severe, it may be necessary to treat the affected animal symptomatically as well as controlling its fleas. A short course of glucocorticoids, e.g. prednisolone, can be used for this purpose.

Prognosis

If flea control is implemented correctly, and the client and patient are compliant, prognosis is excellent.

| Flea Allergic Dermatitis Learning Resources | |

|---|---|

To reach the Vetstream content, please select |

Canis, Felis, Lapis or Equis |

Test your knowledge using flashcard type questions |

Small Animal Dermatology Q&A 13 |

Search for recent publications via CAB Abstract (CABI log in required) |

Flea allergy dermatitis publications |

References

- Tilley, L.P. and Smith, F.W.K.(2004)The 5-minute Veterinary Consult (Third edition) Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

- Thoday, K (1981) Skin diseases of the cat. In Practice, 3(6), 22-35.

- Nuttall, T (2001) Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of atopic dermatitis. In Practice, 23(8), 442-452.

- Perrins and Hendricks (2007) Recent advances in flea control. In Practice, 29(4), 202-207.

| This article has been peer reviewed but is awaiting expert review. If you would like to help with this, please see more information about expert reviewing. |

Error in widget FBRecommend: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt6988943a8ed9e4_76190813 Error in widget google+: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt6988943a95fdc1_69494921 Error in widget TwitterTweet: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt6988943a9b4a77_92793871

|

| WikiVet® Introduction - Help WikiVet - Report a Problem |