Difference between revisions of "Toxoplasmosis - Cat and Dog"

| (98 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | == | + | {{OpenPagesTop}} |

| + | ==Introduction== | ||

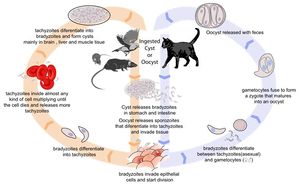

| + | [[Image:Toxoplasmosis Life Cycle.jpg|thumb|right|300px| Life cycle of ''Toxoplasma gondii''. Source: Wikimedia Commons; Author: LadyofHats (2010)]] | ||

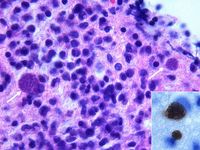

| + | [[Image:Toxoplasmosis Tissue Cyst.jpg|thumb|right|200px| Toxoplasma tissue cyst. Source: Wikimedia Commons; Author: Marvin 101 (2008)]] | ||

| − | ''Toxoplasma gondii'' is | + | Toxoplasmosis is caused by ''[[Toxoplasma gondii]]'' infection. Its life cycle is described in the pathogen page, ''[[Toxoplasma gondii]]''. |

| − | + | ==Pathogenesis== | |

| − | + | The outcome of primary infection depends on the immune status of the host, as well as the location of and degree of injury caused by tissue cysts. Primary infection normally results in chronic disease, where tissue cysts form but clinical signs are not normally apparent. In immunodeficient animals, or in animals with concurrent illness, chronic infections may become symptomatic as the organism is allowed to proliferate. Acute primary infection in these animals can, rarely, prove fatal. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | The mechanism of clinical disease in chronic toxoplasmosis is not fully understood, but may be related to low-level tachyzoite replication, or intermittent antigenaemia and parasitemia<sup>2</sup>. The pathogenesis of disease could also be associated with immunological reactions against the organism through formation and deposition of immune complexes, and delayed hypersensitivity reactions<sup>3</sup>. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | and | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | by | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Signalment== | ==Signalment== | ||

| − | + | Cats more commonly show clinical disease than dogs. Male cats are predisposed, and the average age of the feline toxoplasmosis patient is 4 years (range: 2 weeks to 16 years)<sup>4</sup>. There are no breed predilections. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Clinical Signs== | |

| + | Clinical signs are determined by the site and extent of organ damage by tachyzoites, and may be acute or chronic. Acute signs manifest at the time of initial infection, whereas chronic signs are associated with reactivation of encysted infection during times of immunocompromise. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In '''cats''', disease is most severe in transplacentally infected kittens, which may be stillborn or die before weaning. Those that survive are anorexic and lethargic, with a pyrexia that does not respond to antibiotics. The lungs, liver or CNS may be necrosed, leading to signs such as dyspnoea, respiratory noise, icterus, ascites and neurological signs. Kittens infected neonatally commonly show interstitial pneumonia, necrotising hepatitis, myocardidits, non-suppurative encephalits and uveitis on post-mortem examination<Sup>1</sup>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Cats infected post-natally most commonly display gastrointestinal and/or respiratory signs. Again, animals may be anorexic and lethargic, with an antibiotic non-responsive fever. Vomiting, diarrhoea, icterus or abdominal effusion may be apparent, and the cat may lose weight. Ocular signs such as uveitis, iritis and detachment of the retina are also common. Neurologic signs are seen in less than 10% of patients <sup>4</sup> and may present as circling, torticollis, anisocoria, seizures, blindness or in-coordination. Signs progress rapidly in patients suffering acute disease, in whom respiratory and/or CNS involvement is common. Chronic infections tend to follow a slower course. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In young '''dogs''', ''Toxoplasma gondii'' infection is usually generalised, causing fever, weight loss and anorexia. Dyspnoea, diarrhoea and vomiting may also be seen. Older animals more commonly experience localised infections which are primarily associated with the neural and muscular systems. When neurological signs are seen, they usually reflect diffuse inflammation of the CNS. For example, dogs might suffer seizures, ataxia, paresis or muscle weakness. Although cardiac involvement occurs, this is not normally clinically significant. Ocular changes are rare, but are similar to those described in cats. | ||

===Laboratory Tests=== | ===Laboratory Tests=== | ||

| + | Demonstration of ''Toxoplasma gondii'' in the tissues with associated inflammation is required for the definitive diagnosis of clinical toxoplasmosis. For example, tachyzoites may be seen in blood, cerebrospinal fluid, peritoneal and pleural effusions, aqueous humour or transtracheal washes from clinically ill animals. ''Toxoplasma gondii'' may also be detected in these samples using PCR, tissue culture or animal inoculation techniques<sup>1</sup>. These methods may be employed on tissue biopsies too, as well as examination under haematoxylin and eosin or immunohistochemical staining. Immunohistochemistry is preferred to H&E because it is specific for ''T. gondii''. Demonstration of the organism is often most easily achieved post-mortem, as the size of the sample is not restrictive to the likelihood of seeing ''T.gondii''. In the absence of demonstration of ''Toxoplasma gondii'' in the tissues or fluids ante-mortem, there is no one specific test to diagnose toxoplamosis. However, a combination of various diagnostic procedures can be used to build a presumptive diagnosis. | ||

| − | + | Firstly, clinical signs should be suggestive of toxoplasmosis, despite variation in the presentation of disease between individuals. Although no pathognomic changes for toxoplasmosis are seen on routine haematology, biochemistry and urinalysis, certain results are often seen in ''T. gondii'' infection. For example, most cats show a mild non-regenerative anaemia, and 50% of patients are initially leukopenic due to [[lymphopenia]]. [[Neutropenia]] may occur in conjunction with lymphopenia, and leukocytosis may occur during recovery<sup>4</sup>. Most patients also show and increase in creatine kinase, ALT, SAP, and hypoalbuminaemia is also common<sup>1, 4</sup>. 25% of cats show hyperbilirubinemia and [[icterus]], and [[Pancreatitis|pancreatitis]] may cause low to low normal serum calcium. A mild proteinuria and bilirubinuria are often revealed by urinalysis. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Demonstration of antibodies in serum is indicative of exposure to ''T. gondii'', but does not necessarily show active infection. This could be overcome by testing for ''T. gondii'' antigen or immune complexes, but these methods are currently only available to researchers. Several techniques are commercially available for detection of antibody, including [[ELISA testing|ELISA]], [[Immunofluorescence|immunofluorescent antibody testing]], Sabin-Feldmann dye test, and [[Agglutination|agglutination tests]]. Although these tests are theoretically able to detect all classes of immunoglobulin against ''Toxoplasma gondii'' in many species, it seems that feline serum positive for IgM only often reads as a false negative<sup>5, 6</sup>. Therefore, careful interpretation is necessary, particularly since the IgM antibody class appears to correlate more closely to clinical disease than IgG<sup>7</sup>. IgG antibody persists at high levels for at least six years after infection, and so a single IgG measurement is not particularly useful for clinical diagnosis. A rising IgG titre may be more suggestive of active toxoplasmosis: however, IgG is not produced until 2-3 weeks post-infection which may be too late to be useful in acute cases, and many animals with chronic toxoplasmosis will not be assayed until IgG is already at its maximal titre. A more practically useful form of serology is examination of IgM in aqueous humour or cerebrospinal fluid. IgM, in contrast to IgG and IgA, has only been detected in the aqueous humour and CSF of cats with clinical disease <sup>5, 6</sup>. Therefore, an IgM titre of above 1:64 is highly suggestive of recent or active ''T. gondii'' infection. | |

| + | |||

| + | ''T. gondii'' oocysts may be demonstrated in cat faeces. This diagnostic procedure is not of value in dogs, since as intermediate hosts they do not produce oocysts. Oocysts are roughly 10x12 microns in size and can be seen microscopically following a flotation technique. It is not possible to visibly differentiate between ''Toxoplasma'' oocysts and those from other, non-pathogenic coccidia such as ''Hammondia hammondi'' and ''Besnoitia darlingi'': laboratory animal innoculation is necessary for this. Unfortunately, most cats with clinical toxoplasmosis have already finished shedding oocysts, and so faecal examination is of little use as a stand-alone diagnostic test. However, it will evaluate the zoonotic risk posed by cats showing signs of toxoplasmosis. | ||

===Diagnostic Imaging=== | ===Diagnostic Imaging=== | ||

| + | Radiographs of the thorax in pulmonic toxoplasmosis commonly show patchy alveolar and interstitial pulmonary patterns, but pleural effusions are rare<sup>1</sup>. Abdominal radiographs can show a variety of changes, including hepatomegaly, pertitoneal effusions, lymphadenopathy, intestinal masses, or pancreatitis (seen as reduced contrast in the right cranial quadrant)<sup>1,3</sup>. Myelography, CT or MRI can detect mass lesions in cats with CNS involvement. | ||

| + | |||

===Pathology=== | ===Pathology=== | ||

| + | On post-mortem examination, necrotic foci of up to 1cm diameter can affect many organs. Most commonly, these foci are found in the liver, pancreas, mesenteric lymph nodes, lungs and brain<sup>4</sup>. Ulcers and granulomas may also be seen on the stomach and small intestine. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Biopsy or post-mortem histopathology can reveal tissue cysts containing tachyzoites. | ||

| + | |||

==Treatment== | ==Treatment== | ||

| − | ''' | + | The toxoplasmosis patient does not usually require hospitalisation, unless they are suffering severe disease or cannot maintain adequate nutrition or hydration unaided. Patients showing neurological signs should also be confined and monitored. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Supportive care should be given to cats and dogs with clinical toxoplasmosis as required. The specific treatment for ''Toxoplasma gondii'' infection is '''clindamycin'''. Treatment should generally be given for four weeks, but should continue for at least two weeks after clinical signs have disappeared. Side effects can include acute vomiting and diarrhoea, but stopping treatment for a day or so before reintroducing the drug usually resolves this. Alternatively, a trimethoprim-potentiated sulphonamide may be used for 4 weeks. This is useful in animals where clindamycin is not tolerated or is ineffective in treating CNS toxoplasmosis. Trimethoprim-sulphonamides can cause depression, anaemia, leukopenia and thrombocytopenia, so a complete blood cell count should be performed every two weeks to monitor this. Macrolides such as spiramycin, azithromycin and clarithromycin may also be effective against toxoplamosis, but have not yet been evaluated in cats and dogs. In toxoplasma-induced uveitis, intraocular inflammatory reactions can cause lens luxation and glaucoma, and so animals with uveitis should be prescribed topical glucocorticoids in addition to clindamycin or potentiated sulphonamides. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Animals should be re-examined two days after commencement of treatment, when clinical signs should begin to resolve. If this is not the case, an alternative anti-''Toxoplasma'' drug should be considered. At two weeks, uveitis should be completely resolved, and neurological deficits should show improvement. Two weeks after the owner reports clinical recovery, the animal should be re-examined for a third time, and a decision made as to discontinuation of treatment. It should be noted that some neuromuscular changes may not fully resolve, due to permanent CNS damage. | |

| − | + | Toxoplasmosis may be '''prevented''' through dietary and behavioural modifications. Cats and dogs should not be fed raw meat or animal products or unpasteurised milk. They should also not be permitted to hunt birds or rodents, and access to food-producing animals should be restricted. | |

==Zoonosis== | ==Zoonosis== | ||

| − | + | Toxoplasmosis in cats, who shed infectious oocysts, poses a considerable zoonotic threat. An animal with a positive antibody titre is not necessarily a danger to man, since most of these animals are chronically infected and have ceased to shed oocysts. A naive animal, however, is at risk of becoming infected and shedding oocysts in its faeces - this constitutes a zoonotic threat. Toxoplasmosis in pregnant women can be associated with disastrous consequences, and so contact with cats excreting oocysts, cat litter and raw meat should be avoided. Other humans should take hygienic precautions, such as washing hands, keeping litter trays covered, washing vegetables before cooking to remove oocysts from contaminated soil and wearing gloves while gardening. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | For more information on toxoplasmosis in man, please see [[Toxoplasmosis - Human]]. | ||

==Prognosis== | ==Prognosis== | ||

| + | Within 2-3 days of clindamycin or trimethoprim-sulphonamide administration, most clinical signs should begin to resolve and the prognosis is good. However, anti-''Toxoplasma'' drugs are unlikely to completely eradicate the organism from the host, and so recurrences are common. Ocular and CNS toxoplasmosis respond more slowly to therapy and carry a worse prognosis. Some neuromuscular signs may be persistent due to permanent nervous damage. Animals with hepatic or pulmonary disease have a poor prognosis. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Learning | ||

| + | |literature search = [http://www.cabdirect.org/search.html?q=%28title%3A%28%22toxoplasma+gondii%22%29+OR+title%3A%28toxoplasmosis%29%29+AND+od%3A%28cats%29+ Toxoplasmosis in cats publications] | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |||

==Links== | ==Links== | ||

| + | <big>'''[[Toxoplasmosis - Sheep|Ovine Toxoplasmosis]]''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''[[Toxoplasmosis - Human|Human Toxoplasmosis]]'''</big> | ||

*[http://www.vet.cornell.edu/fhc/brochures/toxo.html Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine Toxoplasmosis Factsheet] | *[http://www.vet.cornell.edu/fhc/brochures/toxo.html Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine Toxoplasmosis Factsheet] | ||

| Line 70: | Line 71: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Category: | + | #Lappin, M (1999) Feline toxoplasmosis. ''In Practice'', '''21(10)''', 578-589. |

| − | [[Category: | + | #Burney, D P et al (1999) Detection of Toxoplasma gondii parasitemia in experimentally inoculated cats. ''Journal of Parasitology'', '''85'''. |

| + | #Dubey, J P (2005) Toxoplasmosis in cats and dogs. ''Proceedings of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association 2005''. | ||

| + | #Tilley, L.P. and Smith, F.W.K.(2004)'''The 5-minute Veterinary Consult (Fourth Edition)''' ''Blackwell Publishing''. | ||

| + | # Lappin, M R (1996) Feline toxoplasmosis: interpretation of diagnostic test results. ''Seminars in Veterinary Medicine and Surgery'', '''11''', 154-160. | ||

| + | # Dubey, J P and Lappin, M R (1998) Toxoplasmosis and neosporosis. In '''Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat''', ''W B Saunders'', 493-503. | ||

| + | #Lappin, M R et al (1989) Clinical feline toxoplasmosis: serologic diagnosis and therapeutic management of 15 cases. ''Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine'', '''3''', 139-143. | ||

| + | #Merck & Co (2008) '''The Merck Veterinary Manual (Eighth Edition)''' ''Merial'' | ||

| + | #Fisher, M (2002) Endoparasites in the dog and cat: 2. Protozoa. ''In Practice'', '''24(3)''', 146-153. | ||

| + | #Quinn, P J and McCraw, B M (1972) Current status of toxoplamsa and toxoplasmosis: A review. '' The Canadian Veterinary Journal'', '''13(11)''', 247-262. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{review}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{OpenPages}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Reproductive Diseases - Cat]][[Category:Cardiac Diseases - Cat]][[Category:Respiratory Diseases - Cat]][[Category:Neurological Diseases - Cat]][[Category:Alimentary Diseases - Cat]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Expert_Review]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Respiratory Diseases - Dog]][[Category:Neurological Diseases - Dog]][[Category:Musculoskeletal Diseases - Dog]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Zoonoses]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Cardiology Section]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:31, 17 October 2013

Introduction

Toxoplasmosis is caused by Toxoplasma gondii infection. Its life cycle is described in the pathogen page, Toxoplasma gondii.

Pathogenesis

The outcome of primary infection depends on the immune status of the host, as well as the location of and degree of injury caused by tissue cysts. Primary infection normally results in chronic disease, where tissue cysts form but clinical signs are not normally apparent. In immunodeficient animals, or in animals with concurrent illness, chronic infections may become symptomatic as the organism is allowed to proliferate. Acute primary infection in these animals can, rarely, prove fatal.

The mechanism of clinical disease in chronic toxoplasmosis is not fully understood, but may be related to low-level tachyzoite replication, or intermittent antigenaemia and parasitemia2. The pathogenesis of disease could also be associated with immunological reactions against the organism through formation and deposition of immune complexes, and delayed hypersensitivity reactions3.

Signalment

Cats more commonly show clinical disease than dogs. Male cats are predisposed, and the average age of the feline toxoplasmosis patient is 4 years (range: 2 weeks to 16 years)4. There are no breed predilections.

Clinical Signs

Clinical signs are determined by the site and extent of organ damage by tachyzoites, and may be acute or chronic. Acute signs manifest at the time of initial infection, whereas chronic signs are associated with reactivation of encysted infection during times of immunocompromise.

In cats, disease is most severe in transplacentally infected kittens, which may be stillborn or die before weaning. Those that survive are anorexic and lethargic, with a pyrexia that does not respond to antibiotics. The lungs, liver or CNS may be necrosed, leading to signs such as dyspnoea, respiratory noise, icterus, ascites and neurological signs. Kittens infected neonatally commonly show interstitial pneumonia, necrotising hepatitis, myocardidits, non-suppurative encephalits and uveitis on post-mortem examination1.

Cats infected post-natally most commonly display gastrointestinal and/or respiratory signs. Again, animals may be anorexic and lethargic, with an antibiotic non-responsive fever. Vomiting, diarrhoea, icterus or abdominal effusion may be apparent, and the cat may lose weight. Ocular signs such as uveitis, iritis and detachment of the retina are also common. Neurologic signs are seen in less than 10% of patients 4 and may present as circling, torticollis, anisocoria, seizures, blindness or in-coordination. Signs progress rapidly in patients suffering acute disease, in whom respiratory and/or CNS involvement is common. Chronic infections tend to follow a slower course.

In young dogs, Toxoplasma gondii infection is usually generalised, causing fever, weight loss and anorexia. Dyspnoea, diarrhoea and vomiting may also be seen. Older animals more commonly experience localised infections which are primarily associated with the neural and muscular systems. When neurological signs are seen, they usually reflect diffuse inflammation of the CNS. For example, dogs might suffer seizures, ataxia, paresis or muscle weakness. Although cardiac involvement occurs, this is not normally clinically significant. Ocular changes are rare, but are similar to those described in cats.

Laboratory Tests

Demonstration of Toxoplasma gondii in the tissues with associated inflammation is required for the definitive diagnosis of clinical toxoplasmosis. For example, tachyzoites may be seen in blood, cerebrospinal fluid, peritoneal and pleural effusions, aqueous humour or transtracheal washes from clinically ill animals. Toxoplasma gondii may also be detected in these samples using PCR, tissue culture or animal inoculation techniques1. These methods may be employed on tissue biopsies too, as well as examination under haematoxylin and eosin or immunohistochemical staining. Immunohistochemistry is preferred to H&E because it is specific for T. gondii. Demonstration of the organism is often most easily achieved post-mortem, as the size of the sample is not restrictive to the likelihood of seeing T.gondii. In the absence of demonstration of Toxoplasma gondii in the tissues or fluids ante-mortem, there is no one specific test to diagnose toxoplamosis. However, a combination of various diagnostic procedures can be used to build a presumptive diagnosis.

Firstly, clinical signs should be suggestive of toxoplasmosis, despite variation in the presentation of disease between individuals. Although no pathognomic changes for toxoplasmosis are seen on routine haematology, biochemistry and urinalysis, certain results are often seen in T. gondii infection. For example, most cats show a mild non-regenerative anaemia, and 50% of patients are initially leukopenic due to lymphopenia. Neutropenia may occur in conjunction with lymphopenia, and leukocytosis may occur during recovery4. Most patients also show and increase in creatine kinase, ALT, SAP, and hypoalbuminaemia is also common1, 4. 25% of cats show hyperbilirubinemia and icterus, and pancreatitis may cause low to low normal serum calcium. A mild proteinuria and bilirubinuria are often revealed by urinalysis.

Demonstration of antibodies in serum is indicative of exposure to T. gondii, but does not necessarily show active infection. This could be overcome by testing for T. gondii antigen or immune complexes, but these methods are currently only available to researchers. Several techniques are commercially available for detection of antibody, including ELISA, immunofluorescent antibody testing, Sabin-Feldmann dye test, and agglutination tests. Although these tests are theoretically able to detect all classes of immunoglobulin against Toxoplasma gondii in many species, it seems that feline serum positive for IgM only often reads as a false negative5, 6. Therefore, careful interpretation is necessary, particularly since the IgM antibody class appears to correlate more closely to clinical disease than IgG7. IgG antibody persists at high levels for at least six years after infection, and so a single IgG measurement is not particularly useful for clinical diagnosis. A rising IgG titre may be more suggestive of active toxoplasmosis: however, IgG is not produced until 2-3 weeks post-infection which may be too late to be useful in acute cases, and many animals with chronic toxoplasmosis will not be assayed until IgG is already at its maximal titre. A more practically useful form of serology is examination of IgM in aqueous humour or cerebrospinal fluid. IgM, in contrast to IgG and IgA, has only been detected in the aqueous humour and CSF of cats with clinical disease 5, 6. Therefore, an IgM titre of above 1:64 is highly suggestive of recent or active T. gondii infection.

T. gondii oocysts may be demonstrated in cat faeces. This diagnostic procedure is not of value in dogs, since as intermediate hosts they do not produce oocysts. Oocysts are roughly 10x12 microns in size and can be seen microscopically following a flotation technique. It is not possible to visibly differentiate between Toxoplasma oocysts and those from other, non-pathogenic coccidia such as Hammondia hammondi and Besnoitia darlingi: laboratory animal innoculation is necessary for this. Unfortunately, most cats with clinical toxoplasmosis have already finished shedding oocysts, and so faecal examination is of little use as a stand-alone diagnostic test. However, it will evaluate the zoonotic risk posed by cats showing signs of toxoplasmosis.

Diagnostic Imaging

Radiographs of the thorax in pulmonic toxoplasmosis commonly show patchy alveolar and interstitial pulmonary patterns, but pleural effusions are rare1. Abdominal radiographs can show a variety of changes, including hepatomegaly, pertitoneal effusions, lymphadenopathy, intestinal masses, or pancreatitis (seen as reduced contrast in the right cranial quadrant)1,3. Myelography, CT or MRI can detect mass lesions in cats with CNS involvement.

Pathology

On post-mortem examination, necrotic foci of up to 1cm diameter can affect many organs. Most commonly, these foci are found in the liver, pancreas, mesenteric lymph nodes, lungs and brain4. Ulcers and granulomas may also be seen on the stomach and small intestine.

Biopsy or post-mortem histopathology can reveal tissue cysts containing tachyzoites.

Treatment

The toxoplasmosis patient does not usually require hospitalisation, unless they are suffering severe disease or cannot maintain adequate nutrition or hydration unaided. Patients showing neurological signs should also be confined and monitored.

Supportive care should be given to cats and dogs with clinical toxoplasmosis as required. The specific treatment for Toxoplasma gondii infection is clindamycin. Treatment should generally be given for four weeks, but should continue for at least two weeks after clinical signs have disappeared. Side effects can include acute vomiting and diarrhoea, but stopping treatment for a day or so before reintroducing the drug usually resolves this. Alternatively, a trimethoprim-potentiated sulphonamide may be used for 4 weeks. This is useful in animals where clindamycin is not tolerated or is ineffective in treating CNS toxoplasmosis. Trimethoprim-sulphonamides can cause depression, anaemia, leukopenia and thrombocytopenia, so a complete blood cell count should be performed every two weeks to monitor this. Macrolides such as spiramycin, azithromycin and clarithromycin may also be effective against toxoplamosis, but have not yet been evaluated in cats and dogs. In toxoplasma-induced uveitis, intraocular inflammatory reactions can cause lens luxation and glaucoma, and so animals with uveitis should be prescribed topical glucocorticoids in addition to clindamycin or potentiated sulphonamides.

Animals should be re-examined two days after commencement of treatment, when clinical signs should begin to resolve. If this is not the case, an alternative anti-Toxoplasma drug should be considered. At two weeks, uveitis should be completely resolved, and neurological deficits should show improvement. Two weeks after the owner reports clinical recovery, the animal should be re-examined for a third time, and a decision made as to discontinuation of treatment. It should be noted that some neuromuscular changes may not fully resolve, due to permanent CNS damage.

Toxoplasmosis may be prevented through dietary and behavioural modifications. Cats and dogs should not be fed raw meat or animal products or unpasteurised milk. They should also not be permitted to hunt birds or rodents, and access to food-producing animals should be restricted.

Zoonosis

Toxoplasmosis in cats, who shed infectious oocysts, poses a considerable zoonotic threat. An animal with a positive antibody titre is not necessarily a danger to man, since most of these animals are chronically infected and have ceased to shed oocysts. A naive animal, however, is at risk of becoming infected and shedding oocysts in its faeces - this constitutes a zoonotic threat. Toxoplasmosis in pregnant women can be associated with disastrous consequences, and so contact with cats excreting oocysts, cat litter and raw meat should be avoided. Other humans should take hygienic precautions, such as washing hands, keeping litter trays covered, washing vegetables before cooking to remove oocysts from contaminated soil and wearing gloves while gardening.

For more information on toxoplasmosis in man, please see Toxoplasmosis - Human.

Prognosis

Within 2-3 days of clindamycin or trimethoprim-sulphonamide administration, most clinical signs should begin to resolve and the prognosis is good. However, anti-Toxoplasma drugs are unlikely to completely eradicate the organism from the host, and so recurrences are common. Ocular and CNS toxoplasmosis respond more slowly to therapy and carry a worse prognosis. Some neuromuscular signs may be persistent due to permanent nervous damage. Animals with hepatic or pulmonary disease have a poor prognosis.

| Toxoplasmosis - Cat and Dog Learning Resources | |

|---|---|

Search for recent publications via CAB Abstract (CABI log in required) |

Toxoplasmosis in cats publications |

Links

- Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine Toxoplasmosis Factsheet

- Feline Advisory Bureau: Toxoplasmosis in cats and man

- The Merck Veterinary Manual - Toxoplasmosis

References

- Lappin, M (1999) Feline toxoplasmosis. In Practice, 21(10), 578-589.

- Burney, D P et al (1999) Detection of Toxoplasma gondii parasitemia in experimentally inoculated cats. Journal of Parasitology, 85.

- Dubey, J P (2005) Toxoplasmosis in cats and dogs. Proceedings of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association 2005.

- Tilley, L.P. and Smith, F.W.K.(2004)The 5-minute Veterinary Consult (Fourth Edition) Blackwell Publishing.

- Lappin, M R (1996) Feline toxoplasmosis: interpretation of diagnostic test results. Seminars in Veterinary Medicine and Surgery, 11, 154-160.

- Dubey, J P and Lappin, M R (1998) Toxoplasmosis and neosporosis. In Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat, W B Saunders, 493-503.

- Lappin, M R et al (1989) Clinical feline toxoplasmosis: serologic diagnosis and therapeutic management of 15 cases. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 3, 139-143.

- Merck & Co (2008) The Merck Veterinary Manual (Eighth Edition) Merial

- Fisher, M (2002) Endoparasites in the dog and cat: 2. Protozoa. In Practice, 24(3), 146-153.

- Quinn, P J and McCraw, B M (1972) Current status of toxoplamsa and toxoplasmosis: A review. The Canadian Veterinary Journal, 13(11), 247-262.

| This article has been peer reviewed but is awaiting expert review. If you would like to help with this, please see more information about expert reviewing. |

Error in widget FBRecommend: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt675b55020bb926_05688848 Error in widget google+: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt675b550210f8c4_21326408 Error in widget TwitterTweet: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt675b5502153a11_81006531

|

| WikiVet® Introduction - Help WikiVet - Report a Problem |