Ruminant Stomach - Anatomy & Physiology

Introduction

The ruminant stomach is composed of 4 separate compartments. Food passes first into the rumen, then reticulum, omasum and finally into the abomasum before entering the duodenum. The first three compartments are adapted to digest complex carbohydrates with the aid of microorganisms which produce volatile fatty acids - the major energy source of ruminants. The last compartments, the abomasum resembles the simple monogastric stomach in structure and function.

The microorganisms in the ruminant stomach also synthesise all of the B vitamins, vitamin C and vitamin K. Vitamin synthesis in the rumen is sufficient for growth and maintenance. Only vitamins E, D and A should be provided in the ruminant diet. Under normal conditions, ruminants will not require B vitamins added in the diet. Cobalt is needed for vitamin B12 synthesis and so cobalt should be provided in the diet or vitamin B12 injected directly into the bloodstream. In stress conditions, vitamin B3 (Niacin) and vitamin B1 (Thiamine) may also need to be provided in the diet.

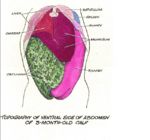

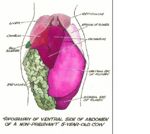

The ruminant stomach occupies most of the left hand side of the abdomen. It is a vast structure, holding up to 60 litres in an adult cow. The rumen holds 80%, reticulum 5%, omasum 8% and abomasum 7% in larger ruminants. In smaller ruminants the proportions are slightly different, with the rumen holding 75%, reticulum 8%, omasum 4% and abomasum 13%.

The different compartments of the ruminant stomach develop from the foregut spindle in foetal life. During embyogenesis and after birth the abomasum is the largest of the compartments (over half of the weight and capacity of the four stomachs) due to the oesophageal groove directing milk from the oesophagus to the rumen into the abomasum, bypassing the reticulum.

Physiology

In most animals, after swallowing, food leaves the oesophagus and enters the stomach. In ruminants, food enters the abomasum after fermentation in the forestomach. The stomach acts as a reservoir in which a semi-solid mass (chyme) is formed from the ingested food before passing into the duodenum. With the exception of water, little absorption occurs in the stomach. Gastric juice is highly acidic, and contains: HCl, produced by the parietal cells which maintains gastric pH at 2, which denatures protein. It also contains pepsin, derived from pepsinogen, produced by zymogen cells. The action of HCl facilitates this. Surface epithelial cells and mucous neck cells produce mucus which forms an alkaline sheet over the epithelial surface. This provides protection from the gastric juice. The cells of the mucosa are renewed at different rates. This is an important considerination in the pathogenesis of certain gastric diseases. Surface epithelial cells and mucous neck cells are replaced about every 3 days. Parietal cells and zymogen cells are produced at a slower rate; the parietal cells have a half-life of 23 days.

Defence Mechanisms

Secretions

Mucus (inhibits contact with mucosa, protects surface), acid (parietal cells) and digestive enzymes (pepsin from gastric chief cells) are all secreted by the ruminant stomach.

Epithelium

Provides a barrier. It is a stratified squamous epithelium; multilayered, with a high cell turnover.

Movement

Continuous movement discourages persistence of insult at the mucosa.

Test Yourself with Ruminant Stomachs Flashcards