Epizootic Lymphangitis/Histoplasmosis - Donkey

Introduction

Epizootic lymphangitis is a contagious, chronic disease caused by the dimorphic fungus, Histoplasma capsulatum var. farciminosum. This disease affects equidae, and occasionally camels, cattle and humans. Epizootic lymphangitis is endemic in parts of Africa, the Middle East and Asia and is believed to be spread by flies feeding on an open wound or from soil contamination of wounds. However, the exact mode of transmission has yet to be fully determined.

Morbidity can be high when animals are frequently gathered together, for example, the ghari (cart) horses found in urban areas of Ethiopia such as Debre Zeit. Spontaneous resolution of disease after a prolonged time period sometimes occurs (Al-Ani, 1999).

For many years it was thought that H. farciminosum was not a major pathogen of donkeys, but recently the organism appears to have adapted to the donkey. Both cutaneous and ocular forms of the disease occur in donkeys. The infection is spread directly from animal to animal and by vector contact. For the most part the condition is highly (if slowly) progressive with involvement in particular of traumatised skin (such as the region of the hocks and hind legs).

Clinical features

The condition is largely restricted to horses. However, the Donkey Health and Welfare Project (DHWP) (A project collaboration supported by The Donkey Sanctuary and based in the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia in Ethiopia ) treated 34 cases of epizootic lymphangitis in donkeys over an 18-month period. These were predominantly of the cutaneous form. An increased incidence of disease in donkeys has paralleled that in horses and mules (B. Endebu, personal communication).

Rare cases of infection in humans have been reported. Therefore, care should be taken when handling infected animals.

Epizootic lymphangitis can resemble glanders caused by Burkholderia mallei, ulcerative lymphangitis caused by Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis or sporotrichosis caused by Sporothrix schenckii. In some parts of Egypt lacrimal histoplasmosis is a common manifestation of the infection (Saleh, 1989; Heragy, 2003). The condition starts with slight conjunctivitis and epiphora. This progresses to blepharospasm and photophobia as the eyelids and lacrimal sac become severely inflamed. Chronic conditions may present with purulent nasal discharge from the affected nostril and fistulation of the lacrimal duct.

Clinical signs

This condition follows a similar pattern in donkeys to that described in the horse. In both, cutaneous and ocular, forms it presents as an ulcerating, pyo-granulomatous dermatitis, tracking along lymphatic vessels which become extensively inflamed. The resulting response causes local exudation and thickening. These lesions are evident mainly in the legs, neck and chest. The condition can also occur as a multifocal pneumonia and as an ocular form with keratitis and conjunctivitis.

The most common form of the disease in donkeys is a conjunctival disease causing major conjunctival infection and inflammation, with characteristic conjunctival thickening and exudate that may extend into the nasolacrimal duct, possibly causing an obstruction or even destruction of the nasolacrimal duct. At this site the resulting epiphora can predispose to facial dermatophilosis and habronemiasis.

The cutaneous form is found predominantly on areas of repeated skin trauma such as harness contact points. The early signs include one or more dermal or subcutaneous nodules. They are usually free of pain when palpated but they can be oedematous and palpation can be resented. Later cords and ulcers develop with discharging tracts that tend to follow cutaneous and subcutaneous lymphatics.

Diagnosis

- Clinical signs

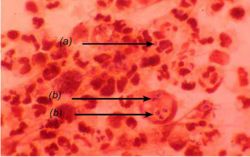

- Microscopic examination. Typical gram-positive, double-contoured, ovoid cells in macrophages and giant cells collected from lesion discharge

- Skin hypersensitivity test

Treatment

Treatment is extremely difficult, requiring repeated and persistent surgical drainage of every identifiable nodule. Dressing of the resulting cavity with strong iodine solution and oral dosing with potassium iodide daily for 30 to 40 days seems to be the best approaches at present. In theory, amphoteracin or fluconazole systemically should be helpful, but it is seldom feasible in places where the disease occurs.

- Various protocols have been used. One of the most successful is intravenous sodium iodide or oral potassium iodide, along with surgical opening of nodules and packing with iodine-soaked gauze

- Owner awareness and compliance is essential for early detection of lesions when treatment is likely to be most successful and for continuation of oral treatment over the required prolonged period

- Treatment of lacrimal histoplasmosis in donkeys has been investigated (Heragy, 2003). Topical antifungal therapy for tear eczema, combined with surgical excision of the granulomatous lesion, was found to be the most satisfactory

Control

- Programmes may include culling of equids showing severe signs of epizootic lymphangitis or, in non-endemic areas, culling any cases introduced

- Careful screening e.g. by clinical examination and skin hypersensitivity test

- Mesh face masks that are advocated for habronemiasis may be useful in the lacrimal form

- Strict attention to hygiene. The organism can be destroyed by disinfectants such as 1% sodium hypochlorite, glutaraldehyde, formaldehyde and phenolics

References

- Anzuino, J. (2008) Exotic infections In Svendsen, E.D., Duncan, J. and Hadrill, D. (2008) The Professional Handbook of the Donkey, 4th edition, Whittet Books, Chapter 14

- Knottenbelt, D. (2008) Skin disorders In Svendsen, E.D., Duncan, J. and Hadrill, D. (2008) The Professional Handbook of the Donkey, 4th edition, Whittet Books, Chapter 8

- Al-Ani, F. K. (1999). ‘Epizootic Lymphangitis in horses: a review of the literature’. Rev.sci.tech.Off.int.Epiz 18(3). pp 691-699.

- Heragy, A.M. (2003). ‘Lacrimal histoplasmosis in the working donkeys of Luxor village’. International Colloquium on Working Equines, Al Baath University, Hama, Syria. 20 - 26 April 2002. SPANA, 14 John Street, London WC1N 2EB.

- Saleh, M. (1989). ‘Lacrimal histoplasmosis in donkeys’. The Professional Handbook of the Donkey, 2nd Edition. E. D. Svendsen (ed). Whittet Books Limited, London. pp 122-129.

|

|

This section was sponsored and content provided by THE DONKEY SANCTUARY |

|---|