Difference between revisions of "Osteomyelitis"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

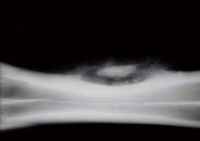

[[Image:Cattle localised osteomyelitis with sequestrum.jpg|right|thumb|200px|<small><center>Localised osteomyelitis plus sequestrum (Image sourced from Bristol Biomed Image Archive with permission)</center></small>]] | [[Image:Cattle localised osteomyelitis with sequestrum.jpg|right|thumb|200px|<small><center>Localised osteomyelitis plus sequestrum (Image sourced from Bristol Biomed Image Archive with permission)</center></small>]] | ||

| Line 76: | Line 75: | ||

{{review}} | {{review}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Musculoskeletal Diseases - Dog]] | [[Category:Musculoskeletal Diseases - Dog]] | ||

[[Category:Expert Review]] | [[Category:Expert Review]] | ||

Revision as of 23:55, 3 August 2011

Introduction

Osteomyelitis describes inflammation and infection of the medullary cavity, cortex and periosteum of bone. This occurs most commonly at the metaphyses and epiphyses.

It can arise from direct penetration of bone by microorganisms or by haematogenous spread. The latter is the most common cause of osteomyelitis in young animals. It can also accompany septic arthritis, more commonly in foals. Other causes include: open fractures and traumatic injuries, foreign bodies, extension of soft tissue infection etc.

Organisms commonly isolated include: Actinomyces pyogenes, Salmonella, E.coli, Klebsiella, Streptococci.

Fungal organisms have also been implicated, and diseases, based on geographic distributions, include Coccidoides immitis (southwestern USA), Blastomyces dermatitidis (southeastern USA), Histoplasma capsulatum (central USA), Cryptococcus neoformans and Aspergillus (worldwide).

Pathogenesis involves: osteoclastic bone resorption stimulated by prostaglandin and cytokines. Blood vessels become occluded and there is tissue necrosis with thickening of cartilage and persistence of infection. The affected area my be surround by fibrous inflammatory tissue.

Metaphyseal abscesses may develop.

Sequestra may also develop, and are surrounded by granulation tissue. These are isolated from osteoclastic resorption and may persist for a long time and obstruct repair.

Risk factors include: open fracture and bone contamination, soft tissue trauma, bite and claw wounds, migrating foreign body, orthopaedic surgery and orthopaedic implants, cortical bone allograft and immunodeficiency.

Clinical Signs

Clinical signs may be acute or chronic and can vary widely.

Acute disease in small animals presents as a sudden onset 'systemic illness with pyrexia, lethargy, limb pain, and local signs of acute inflammation (heat, swelling, pain, redness, loss of function).

Chronic cases are usually associated with chronic draining tracts, non-healing ulcers, pain, secondary muscle atrophy and joint stiffness.

Unhealed fractures with a concurrent infection may show instability, crepitus and limb deformity.

Vertebral osteomyelitis which affects the spinal cord leads to spinal pain. Neurological deficits, such as paresis or paralysis, can develop if there is damage to the spinal cord due to vertebral body fracture, or compression of the cord due to an abscess.

Large animal cases often present with a non-healing wound and draining tract with soft tissue swelling.

Cattle with lumpy jaw present with a distorted face and draining fistulous tracts around the mandibular area.

Diagnosis

Radiography is a very helpful tool, especially in chronic cases. It may reveal bone lysis (widening of fracture gaps), sequestration (avascular segment of cortical bone), reactive periosteal new bone.

If orthopaedic surgery has been performed, radiography might reveal a loosening of any implants.

Deep fine-needle aspiration or biopsies can be cultured to identify the causative organism.

Histopathology can help diagnose fungal infections and rule out neoplasia.

Culture of the purulent fluid from the draining tracts might be misleading due to skin contaminants.

Blood cultures may be useful in cases with systemic bacteraemia or septicaemia.

Treatment

Both medical and surgical therapies can be used.

Long-term oral or injectable antimicrobials such as cephalexin, clindamycin, enrofloxacin or combinations should be administered. Results of the culture and sensitivity tests should be taken into account when choosing an antimicrobial.

Acute infections may resolve with antimicrobial therapy alone provided there is limited bone necrosis and no fracture.

Surgical debridement and lavage of the wound along with removal of any loose implants should generally also be carried out, especially in chronic cases. Open or closed wound drainage can be used.

In chronic, refractory small animal cases, limb amputation may be necessary.

In vertebral osteomyelitis cases, antibiotic therapy might be sufficient, or surgery to decompress the spinal cord may be necessary.

Patient progress should be monitored with repeat radiographs every 4-6 weeks, and repeat bone culturing might be necessary if a persistent infection is suspected.

Prognosis is variable and based on the severity and chronicity of the infection and the organism involved.

| Osteomyelitis Learning Resources | |

|---|---|

Test your knowledge using flashcard type questions |

Equine Orthopaedics and Rheumatology Q&A 12 |

References

Shires, P. (2005) The 5-minute veterinary consult: musculoskeletal disorders Wiley-Blackwell

Kahn, C. (2005) Merck Veterinary Manual Merck and Co

Fenner, W. (2000) Quick Reference to Veterinary Medicine Wiley-Blackwell

| This article has been peer reviewed but is awaiting expert review. If you would like to help with this, please see more information about expert reviewing. |