Difference between revisions of "Rumen - Anatomy & Physiology"

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 14:05, 2 November 2022

Introduction

The rumen is the first chamber of the ruminant stomach. It is the largest chamber and has regular contractions to move food around for digestion, eliminate gases through eructation and send food particles back to the mouth for remastication. The rumen breaks down food particles through mechanical digestion and fermentation with the help of symbiotic microbes. Volatile fatty acids are the main product of ruminant digestion.

Structure

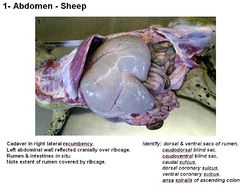

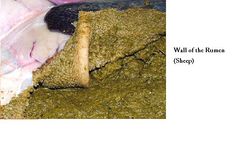

Grooves correspond with thickened smooth muscle pillars on the inside of the rumen. Ruminal pillars divide the dorsal and ventral ruminal sacs. Coronary pillars divide the caudal blind sacs. The cranial pillar divides the dorsal and cranial sacs. It is covered by the greater omentum. The rumen is 38-40°C, anaerobic and has a pH of 6.7. It is buffered and has a large holding capacity. Water intake lowers the ruminal temperature so bacteria are tolerant to temperature changes towards the lower end of the scale. Objects are often lodged in the rumino-reticular fold. When the rumen contracts, the object can be pushed through the reticulum wall into the pericardium and heart.

The rumen is laterally compressed and extends from the cardia at the level of the 8th rib to the pelvic inlet. The serosa covers the entire rumen except dorsally where the rumen attaches to the abdominal roof allowing more freedom for ruminal movement and expansion. Ruminal contractions can be felt for in the left paralumbar fossa. 1-2 contractions should be felt per minute. The opening at the cardia into both the rumen and reticulum is called the reticular groove (see oesophageal groove).

Function

The rumen is involved in waste removal. Simpler products of digestion are assimilated directly, others continue down the digestive tract for further digestion. It mixes food and moves it forwards through the stomach chambers. Sensors in the rumen can determine the coarseness of the food. Coarse, tough feed needs stronger and more frequent ruminal contractions. The vagus nerve (CN X) is needed for control of stomach movements. The reflex control is through sensory receptors in the medulla.

See rumination and eructation.

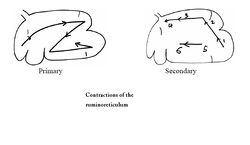

Ruminoreticular contraction

The contractions have two main functions:

- Primary contraction mixes food by a ruminoreticuluar mixing cycle. There are 2 contractions of the reticulum (2nd most powerful) which continue over the rumen. Ingesta flows from the reticulum to cranial rumenal sac and then to reticulum (or ventral sac). It occurs every 60 seconds.

- The secondary contraction lets gas out (see eructation). Ingesta flows from the ventral blind sac to the dorsal blind sac then to dorsal sac (eructation) and to the ventral sac.

Vasculature

The rumen receives blood from the celiac artery which branches into the right and left ruminal arteries.

Innervation

The rumen is innervated by the dorsal vagus nerve (CN X) (most important) and ventral vagus (CN X) nerve.

Lymphatics

The caudal mediastinal lymph node enlargement puts pressure on the dorsal vagus effecting ruminal contractions. There are numerous small lymph nodes scattered in the ruminal grooves. The lymph drains to larger atrial nodes between the cardia and the omasum, then to the cistera chyli.

Rumen Microbes

The rumen has a variety of microbes that can utilise many substrates. The dominance of different bacterial species depends on pH. Ergo, microbial populations are not constant. Microbes digest cellulose and hemi-cellulose and provide a source of all amino acids. Microbes also synthesise vitamins (especially the B vitamins).

Rumen Microbial Population

Bacteria There are over 2000 species, 99.5% are obligate anaerobes.

Protozoa Large, unicellular organisms that prey on bacteria. Numbers are affected by diet.

Fungi Digest fibre. Numbers present are usually low.

Common Rumen Microbes

| Species | Type | pH |

|---|---|---|

| Ruminococcus flavefauens | Fibre | 6.15 |

| Fibrobacter succinogens | Fibre | 6 |

| Megashpaera eisdeni | Lactate user | 4.9 |

| Streptococcus bovis | Lactate producer | 4.55 |

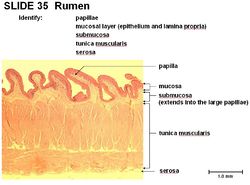

Histology

The rumen has a keratinised stratified squamous epithelium. It is non-glandular and has no lamina muscularis.

There are two thick layers of tunica muscularis, the inner circular and the outer longitudinal. The interior surface of the rumen forms numerous papillae. The papillae can be long and foliated or short and pointed. They are up to 6mm in length. Animals fed on rough grass or in the dry season have longer papillae, whereas animals fed on digestible feed or in the wet season have shorter papillae (1-2mm in length). There are fewer papillae present dorsally. They increase the surface area for volatile fatty acid absorption. The upper keratinised layer of papillae also protects the rumen against abrasion. The deeper layers of papillae metabolise the volatile fatty acids.

Species Differences

Small Ruminants

Sheep and goats have a larger ventral ruminal sac than dorsal ruminal sac. The cranial mesenteric artery and celiac artery come off the same root.

Bovine

The cranial mesenteric artery and celiac artery are close in the cow. Dairy cows have a rumen pH of 5.5 due to more digestible feed.

Links

Click here for information on the Reticulum - Anatomy & Physiology

Click here for information on the Omasum - Anatomy & Physiology

Click here for information on the Abomasum- Anatomy & Physiology

| Rumen - Anatomy & Physiology Learning Resources | |

|---|---|

Test your knowledge using flashcard type questions |

Rumen Flashcards |

Selection of relevant videos |

Lateral view of the Abdomen of a young Ruminant Sections of the Ruminant Stomach Left sided topography of the Ovine Abdomen and Thorax Right sided topography of the Ovine Abdomen Structure of the ruminant forestomachs |

Anatomy Museum Resources |

Sheep Rumen (external aspect) |

Webinars

Failed to load RSS feed from https://www.thewebinarvet.com/gastroenterology-and-nutrition/webinars/feed: Error parsing XML for RSS