Coagulation Tests

Also known as: coagulation profile — clotting profile — clotting tests — tests of haemostasis

Introduction

Bleeding diatheses can occur as a result of a failure of primary haemostasis (vascular contraction and platelet aggregation) or of secondary haemostasis (the coagulation cascade). The clinical presentation can give some indication as to the nature of the disorder. Petechiation or ecchymoses of the skin or mucosal surfaces, epistaxis, haematuria, melena, intraocular haemorrhage, bleeding after venipuncture or incision, are usually associated with disorders of primary haemostasis for example thrombocytopenia. Haematoma, bleeding into a body cavity, haemarthrosis or delayed bleeding after surgery, are usually associated with an abnormality of secondary haemostasis for example coagulopathy. Consideration of the age of onset, breed, possible previous episodes, recent surgery or trauma, drug therapy, access to toxins and any similar familial history may all be relevant.

References: NationWide Laboratories

Normally, haemostastis is maintained by three key events:

- Primary haemostasis involves platelets and the blood vessels themselves and is triggered by injury to a vessel - platelets become activated, adhere to endothelial connective tissue and aggregate with other platelets. A fragile plug is formed which helps to stem haemorrhage from the vessel. Substances released from platelets during primary haemostasis include vasoactive compounds to induce vasoconstriction and other mediators that cause continued platelet activation and aggregation, as well as contraction of the platelet plug. Primary haemostasis ceases once defects in the vessels are sealed and bleeding stops.

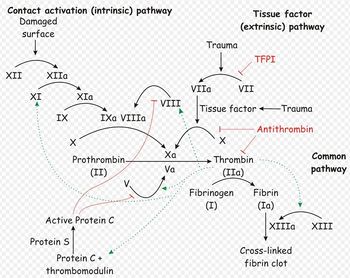

- Secondary haemostasis occurs when proteinaceous clotting factors interact in a cascade to produce fibrin to reinforce the clot. Two arms of the cascade are activated simultaneously to achieve coagulation: the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. The intrinsic pathway is activated by contact with collagen due to vessel injury and involves the clotting factors XII, XI, IX and VIII. The extrinsic pathway is triggered by tissue injury and is effected via factor VII. These pathways progress independently before converging at the common pathway, which involves the factors X, V, II and I and ultimately results in the formation of fibrin from fibrinogen. Factors II, VII, IX and X are dependent upon vitamin K to become active.

- Fibrinolysis is the final stage of restoring haemostasis - it prevents uncontrolled, widespread clot formation and breaks down the fibrin within blood clots. The two most important anticoagulants involved in fibrinolysis are antithrombin III (ATIII) and Protein C. The end products of fibinolysis are fibrin degratation products (FDPs).

Abnormalities can develop in any of the components of haemostasis. Disorders of primary haemostasis include vessel defects (i.e. vasculitis), thrombocytopenia (due to decreased production or increased destruction) and abnormalities in platelet function (e.g. congenital defects). These lead to the occurence of multiple minor bleeds and prolonged bleeding times; petechial or ecchymotic haemorrhages may be seen for example, on the skin and mucous membranes, or ocular bleeds may arise. Generally, intact secondary haemostasis prevents major haemorrhage in disorders of primary haemostasis. When secondary haemostasis is abnormal, larger bleeds are frequently seen. Haemothorax, haemoperitoneum, or haemoarthrosis may occur, in addition to subcutaneous and intramuscular haemorrhages. Petechiae and ecchymoses are not usually apparent, as intact primary haemostasis prevents minor capillary bleeding. Examples of secondary haemostatic disorders include clotting factor deficiencies (e.g. hepatic failure, vitamin K deficiency, hereditary disorders) and circulation of substances inhibitory to coagulation (FDPs in disseminated intravascular coagulation, lupus anticoagulant). If fibrinolysis is defective, thrombus formation and infarctions may result. Thrombus formation may be promoted by vascular damage, circulatory stasis or changes in anticoagulants or procoagulants. For example, ATIII may be decreased. This can occur by loss due to glomerular disease or accelerated consumption in disseminated intravascular coagulation or sepsis.

It is therefore important that all aspects of haemostasis can be independently evaluated. This will help to identify the phase affected and to pinpoint what the abnormality is. There are tests available to assess primary haemostasis, secondary haemostasis and fibrinolysis.

Tests Evaluating Primary Haemostasis

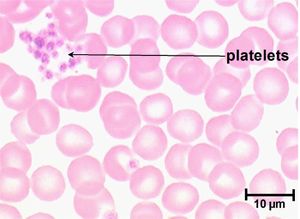

Primary haemostasis is dependent on the activity of platelets and, to a lesser extent, the blood vessels themselves. Platelets are the smallest solid formed component of blood, and are non-nucleated, flattened disc-shaped structures1. Their activity leads to vascoconstriction and the formation of platelet plugs to occlude vessel defects. Platelets develop in the bone marrow, and have a life span of around 7.5 days. Around two thirds of platelets are found in the circulation at any one time, with the remainder residing in the spleen1.

Apart from unusual cases involving vasculitis, there are two causes of defects in primary haemostasis: thrombocytopenia (reduced platelet number), or thrombocytopathia (defective platelet function)2.

Blood Film examination

Examine a fresh air dried blood smear after staining with Diff Quick. Platelet numbers are assessed by counting the mean number of platelets per 100x oil immersion field in the monolayer of the smear (count ten fields over the width of the smear). Assess for the presence of platelet clumps (these may be small or large, light to dark basophilic aggregates usually seen in the feathered edge). When present, platelet clumps may render the manual estimate and the automated count spuriously low. For an estimate of the platelet count, consider that each platelet is equivalent to between 12-20,000/ul. Multiplying the average platelet number per field by 12-20,000 will give an estimate of the platelet count/ul.

| Plarelets per oil inmersion field | |

|---|---|

| Normal | 10-25 |

| Mild thrombocytopenia | 6-9 |

| Moderate thrombocytopenia | 4-5 |

| Marked thrombocytopenia | 0-3 |

When scanning the blood smear, check for the presence of large platelets (shift platelets). These are immature, hyper-reactive platelets that correspond to a regenerative response in the bone marrow to platelet destruction, consumption or loss. Cavalier King Charles spaniels may have large platelets with decreased platelet counts due to inherited macrothrombocytopaenia.

References: NationWide Laboratories

Platelet Number

A platelet count can give valuable information in all critically ill animals and is an essential laboratory test for patients where there are concerns about abnormal bleeding. Platelet numbers may be rapidly estimated by examination of a stained blood smear, or quantified by manual or automated counting techniques. Platelet clumping can give an artificially low platelet count when using manual or automated counting methods. To estimate the platelet number using a blood smear, the slide should first be scanned for evidence of clumping that would artificially reduce the count. The average number of platelets in ten oil-immersion fields should be counted, and a mean calculated. Each platelet in a high-power field represents 15,000 platelets per microlitre2. A "normal" platelet count therefore gives around 10-15 platelets per oil-immersion field.

The reference range given for platelet number is usually around 200-500x109 per litre, although this varies depending on the laboratory equipment used. Clinical signs due to thrombocytopenia are not commonly encountered until the platelet count drops below 50x109/l, when increased bleeding times may be seen. Haemorrhage during surgery becomes a concern with counts lower than 20x109/l, and spontaneous bleeding arises when platelets are fewer than 5x109/l2. These cut-offs are lowered if platelet function is concurrently affected by other factors such as the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs1.

Buccal Mucosal Bleeding Time (BMBT)

Assessment of BMBT is indicated in animals with signs suggesting a disorder of primary haemostasis in which the platelet count is within reference limits. This test evaluates primary haemostasis (platelet adhesion via von Willebrand factor and aggregation to form a platelet plug). It records the time to cessation of bleeding following a standard incision in the buccal mucosa. Use of manual restraint may be possible in dogs but sedation (ketamine and acepromazine) or anaesthesia is required for cats. BMBT is consistently prolonged in thrombocytopenia, severe azotaemia, and von Willebrand’s disease. Drugs which primarily affect platelets, for example aspirin and phenylbutazone, prolong the BMBT.

Normal values: <4.2minutes in the dog; <3.3minutes in the cat.

References: NationWide Laboratories

The buccal mucosal bleeding time is a simple test that gives a rapid assessment of platelet function, providing platelet numbers are normal. If platelet numbers are below 50x109/l, this test should not be performed since the results will be affected by thrombocytopenia, making them unreliable. The small wound inflicted may also not stop bleeding easily.

To perform the BMBT test, a standardised tool producing a uniform incision is used to incise the buccal mucosa of the upper lip2,3, and the time between making the incision and the cessation of bleeding is measured2. During the procedure the lip should be kept turned outwards, with excess blood being gently absorbed at a site away from the incision, without disturbing clot formation or applying pressure. Normally, bleeding should stop within 3 minutes, and a BMBT of greater than 5 minutes is considered prolonged2.

Acquired platelet function abnormalities can be drug induced, for example by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs2,3, or can be secondary to uraemia. Hereditary defects in platelet function also exist, and von Willebrand's disease is the most common of these.

The BMBT is influenced by all the aspects of this phase, including vasoconstriction, platelet adherence and plately aggregation. Although this makes BMBT an effective screening test for the vascular/platelet (primary) phase of haemostasis, it also means it is not purely a test for thrombocytopathia, as it is often considered: BMBT depends on an intact vasospastic response and adequate platelet numbers as well as platelet function3. BMBT is a fairly crude test, and has been found to be normal in some patients with a known platelet function disorder and vice versa3. The results of this test therefore should be interpreted with some caution.

Protocol

- Restraint, sedation or anaesthesia may be required depending on the patient. Sedation by the s/c route is recommended due to the possibility of impaired haemostasis

- With the patient in lateral recumbency, the upper lip is folded upwards and held in place with a bandage which is tight enough to result in vessel congestion. (See reference articles for a diagram of this procedure)

- A standard incision is made in the buccal mucosa with the Surgicutt device selecting an area of mucosa without visible blood vessels. Place the device firmly against the buccal

mucosa but do not press. Depress the trigger, commence timing and remove the device approximately one second after triggering

- Blot the flow of blood at 5 second intervals with filter paper, being careful not to touch the edge of the wound, and record the time to cessation of bleeding. The BMBT is the mean bleeding time for the two incisions. If bleeding continues for >20 minutes then the bandage should be removed and timing stopped

Interpretation

The normal time to cessation of bleeding is:

- 1.7 to 3.3 minutes in restrained, unsedated or unanaesthetised dogs

- <4.3 minutes in sedated or anaesthetised dogs

- <3.3 minutes in anaesthetised cats

A prolonged BMBT may be seen in cases of thrombocytopenia, severe azotaemia and von Willebrands disease. Dogs with coagulation defects may have a normal BMBT although prolonged rebleeding after primary haemostasis may be seen.

Protocol and Interpretation References: NationWide Laboratories

Clot retraction

The clotted sample should be examined hourly and should reduce to about 50% of its original volume within 2 hours. This is a crude test of platelet function.

Tests Evaluating Secondary Haemostasis

Secondary haemostasis describes the formation of a cross linked fibrin meshwork in the blood clot and is dependent on soluble coagulation factors. Abnormalities in secondary coagulation can occur if there are insufficient coagulation factors, inactive coagulation factors or inhibition of factors. To recap, the soluble coagulation factors are traditionally divided into the intrinsic, extrinsic and common pathways.

Whole blood clotting time

This is a crude test of haemostatic function. Prolonged clotting times are associated with abnormalities of the intrinsic pathway and thrombocytopenia (platelet phospholipid is required for clot formation). Normal results do not exclude a coagulopathy. The whole blood clotting time requires the minimum of equipment and can be readily performed in practice but the activated coagulation time is preferred. Method for whole blood clotting time:

- Perform a venipuncture, discard the first 0.25-0.5ml of blood

- Withdraw a further 3-4ml and place 1ml into each of 2 glass tubesPlace tubes in a water bath at 37 (or as close as possible)

- Start the timer

- Tip the tubes gently to 90 degrees every 30 seconds until the blood has coagulated

- The average coagulation time is calculated. Although the size of tubes and the temperaturewill have an effect, clotting would be expected within 13 minutes for the dog and 8 minutes for the cat.

References: NationWide Laboratories

Activated Clotting Time

The activated clotting time (ACT) is a more sensitive test than the whole blood clotting time but requires the use of a specially treated tube. The tube is filled, mixed by inversion and placed in a water bath at 37 C for 45 seconds (cats) and 60 seconds (dogs). It is then tilted at 5 second intervals until the first clot is observed. This is the end point in this test. The ACT is usually <165 seconds in cats and <95 seconds in dogs. It will be prolonged where there is an abnormality of the intrinsic or common pathway and in severe thrombocytopenia. ACT is not a sensitive test for diagnosing a coagulopathy as a factor must be decreased to <5% of normal to prolong the coagulation time.

References: NationWide Laboratories

The activated clotting time (ACT) allows rapid evaluation of secondary haemostasis. The ACT is the time taken for 2ml of fresh whole blood to clot in a tube with a contact activator (diatomaceous earth2), but an automated analyser can perform a test with a similar principle. The reaction must occur at body temperature to give a reliable indication of haemostatic ability: this can be achieved by the use of a warm water bath, or in an emergency by holding the tubes under an arm.

The contact activator used in the ACT test triggers the intrinsic pathway, and so ACT allows assessment of the intrinsic and common pathways. ACT will therefore be prolonged when factors I, II, V, VIII, IX, X, XI or XII are deficient or abnormal, such as in DIC, liver disease, vitamin K antagonist toxicosis or haemophilia A or B2. Thrombocytopenia may also increase ACT.

Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time

The APTT measures the time necessary to generate fibrin from activation of the intrinsic pathway3. It therefore assesses functionality of the components of the intrinsic and common pathways of coagulation. The test is performed on citrated plasma, and so blood should be collected into a sodium citrate tube if the APTT test is to be undertaken. Once a sample is obtained, factor XII is activated by an external agent that will not also activate factor VII, such as kaolin1, 3. Since the intrinsic arm of the cascade requires platelet factors to function, the test also provides a phospholipid emuslion in place of these factors. Calcium is added, the preparation is incubated, and the time for clumping of kaolin is measured. Classically, partial thromboplastin time was measured after activation by contact with a glass tube, but use of an external activating agent in the newer, "activated" partial thromboplastin time method makes results more reliable3.

APPT evaluates the same pathways as ACT, and so will be prolonged by abnormalities or deficiencies in factors XII, XI, IX, VIII, X, V, II or I. However, APTT is not affected by thrombocytopenia and is also considered to be a more sensitive test than ACT: APTT becomes prolonged when 70% of a factor is depleted, compared to 90% depletion required to prolong the ACT. APTT can also be prolonged in the presence of a circulating inhibitor to any of the intrinsic pathway factors. To differentiate factor deficiency from inhibition, a "mixing study" can be performed where the test is repeated on a 1:1 mix of patient and normal plasma. Complete correction indicates a deficiency, and partial or no resolution shows that an inhibitor is present. This difference stems from the above mentioned fact that the APTT will be normal in the presence of 50% normal activity3.

Conditions in which APTT is prolonged include inherited disorders, such as haemophilia A and B and other congential absences of intrinsic and common factors. Acquired factor deficiency also occurs, for example with vitamin K deficiency, liver dysfunction, prolonged bleeding or disseminated intravascular coagulation. The most common inhibitors found to prolong APTT are the antithrombins, which inhibit the activity of thrombin on the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin. Examples include heparin and fibrin degradation products.

Occasionally, a shortened APTT is seen. This may reflect increased levels of activated factors in a hypercoagulable state, for example in the early stages of DIC3.

Prothrombin Time

Prothrombin time (PT) gives an assessment of the extrinsic and common pathways by measuring the time necessary to generate fibrin after activation of factor VII3. It is performed manually or by an automated analyser2 using citrated plasma1, 3. Blood should therefore be collected into a sodium citrate tube if prothrombin time is to be performed. For the manual test, as a quality control measure it is normal to undertake the test in a sample from an unaffected patient to compare the time taken to clot between the two samples - this will account for variables such as variations in the technique of performing the manual test. The test procedure involves adding rabbit brain thromoplastin to the patient's plasma once it has been warmed to 370C and recording the time taken for the sample to clot1.

A prolonged PT may reflect a factor deficiency or the presence of a circulating inhibitor of coagulation. Repeating the test using a mix of test plasma and "normal" plasma can help differentiate these possibilities: PT returns to normal limits when normal plasma is added to factor-deficient plasma, but no change is seen when this is added to plasma containing inibitors3. PT is more sensitive than APTT for factor deficiencies.

PT is affected by abnormalities or deficiencies in coagulation factors I, II, VII or X, for example in DIC, liver disease, endotoxaemia or poisoning with vitamin K antagonists. Inherited defects are possible. PT is also prolonged by the presence of circulating anticoagulants. Inhibitors are often directed at factor X or thrombin and include fibrin degradation products and heparin3. As factor VII has the shortest half-life of all the coagulation factors, if a patient is suffering a coagulation factor deficiency a prolonged PT is seen before a prolonged PTT as this factor is depleted most rapidly.

Tests for Individual Clotting Factors

Some specialised laboratories offer tests for specific clotting factors. A sodium citrate sample is required.

Proteins Induced by Vitamin K Antagonism Test

Factors II, VII, IX and X are produced in the liver as non-functional precursors which become activated by carboxylation of their glutamic acid residues in the presence of vitamin K. The inactive precursors are absent from the circulation of normal animals, as they are stored in the microsomal system of the liver. However, the absence of vitamin K results in an increase in these precursors, which spill into the circulation and become known as Proteins Induced by Vitamin K Antagonism (PIVKA). Concurrently, the levels of active factors II, VII, IX and X are depleted.

The PIVKA test is modified version of PT that is designed to be more sensitive than PT for abnormalities in the vitamin-K dependent clotting factors. Diluted plasma is used to give longer clotting times, and a test-specific reagent is added. The PIVKA test is reported to be sensitive to both increases in PIVKAs and decreases in the functional coagulation factors II, VII, IX and X, although there is some debate as to whether PIVKAs actually inhibit the reaction. Although intended to be more sensitive than the PT for factors of interest, studies in dogs have shown that a PIVKA test offers little diagnostic advantage4. Additionally, only certain laboratories offer the test and the turnaround time is longer than PT.

The PIVKA test is prolonged in vitamin K deficiency. This can result from anticoagulant rodenticide toxicity or cholestasis. Some animals in disseminated intravascular coagulation also have a prolonged PIVKA test.

Tests Evaluating Fibrinolysis

Fibrin Degradation Products

A latex agglutination test is available for fibrin degradation products (FDP). To perform the test, anti-FDP antibodies attached to latex particles are added to serial dilutions of test serum. If agglutination is seen at a particular dilution, the test is positive. The most dilute sample that agglutinates gives the overall result of the test. Normal values are between 1/4 and 1/16.

Although the test is simple to perform, interpretation may be challenging. This is because other small fragments involved in the homeostasis of fibrinogen and fibrin are measured by the test in addition to bona fide fibrin degradation products. In general, an increase in FDP corresponds to increased fibrinolysis. This can be due to a local problem of fibrin generation such as thrombosis, trauma or chronic bleeding, or be related to a systemic process, usually DIC3.

Laboratory testing

Coagulation screen

This is the initial recommended test for further investigation of a bleeding disorder. It includes:

Haemogram. RBC count, haemoglobin concentration, haematocrit, MCV, MCH, MCHC, WBC count and differential, platelet count and cellular morphology report

One stage prothrombin time (OSPT). This is prolonged in deficiencies of the extrinsic pathway (such as occurs in rodenticide poisoning; factor VII deficiency/antagonism) and the common pathway. Factors in the common pathway include fibrinogen (I), thrombin (II) and factors V and X

Activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT). This is prolonged in deficiencies of the intrinsic and common pathways. The APPT only becomes prolonged when factor activity is decreased to <30% of normal. The intrinsic pathway includes factors XII, XI, IX, and VIII and is initiated by contact activation. This test is more sensitive than the ACT

Factor XII deficiency is relatively common in cats (DSH, DLH, Siamese, Himalayan) and has been recognized in dogs. Affected animals have markedly prolonged APTT and ACT but do not have a clinical bleeding disorder since factor XII is not essential for normal haemostasis.

Samples required

EDTA, fresh air dried smears.

Citrate plasma from the patient and, if possible, from a control.

Sampling

Take blood before initiating therapy. Dispatch the samples immediately to the laboratory. If this is not possible, separate the citrated plasma, decant into a plain tube without anticoagulant (white doughnut) and refrigerate.

Specific additional tests may be recommended, depending upon the results of the initial screen.

Antiplatelet antibodies

Testing for antiplatelet antibodies is not available, immune-mediated thrombocytopenia (IMT) is a diagnosis of exclusion. IMT may be primary, or secondary to infections, myeloproliferative disease, neoplasia and SLE. There is usually a profound thrombocytopenia but normal OSPT and APTT .

Von Willebrand factor

Von Willebrand factor is important for the adhesion of activated platelets and formation of the primary platelet plug in the early stages of haemostasis; it is activated by tissue damage. Canine von Willebrand’s disease is the most common inherited haemostatic disorder, affecting many breeds of dog, including Doberman Pinschers, Scottish terriers, Shetland sheepdogs and Chesapeake Bay retrievers. There is no particular pattern to the expression of the bleeding tendency. For certain breeds there is a genetic test to clarify von Willebrand status. Please contact the laboratory to discuss test availability.

Where genetic testing is not available, assay for von Willebrand factor (citrated plasma) is possible. The administration of DDAVP (desmopressin) raises levels and this can be utilised clinically (for example, to blood donors before harvesting blood).

Haemophilia A (factor VIII)

Haemophilia A (factor VIII deficiency) is reportedly the most common inherited deficiency of secondary haemostasis.

A test for factor VIII deficiency is performed on citrated plasma. Factor VIII is a cofactor in the intrinsic pathway and deficiencies prolong the APTT. It is sex-linked: affected animals are males while females may be carriers. If the deficiency is marked (<1% of normal factor VIII) the animal will suffer from life-threatening bleeding episodes from a young age. There is a moderate form of the disease, recognised particularly in the German Shepherd.

Fibrin degradation products (FDPs)

Assay not available

D-dimer

D-dimers are a specific product resulting from the lysis of cross-linked fibrin by the fibrinolytic system. An increased D-dimer concentration in plasma indicates that an excess amount of fibrin has been formed within the vascular space and is undergoing fibrinolytic degradation. D-dimer testing has been shown to be sensitive and specific in providing support for a diagnosis of DIC in dogs and is more sensitive than FDP for the same purpose.

Elevations may, however, be seen in any fibrinolytic condition, for example post surgical wound healing and internal haemorrhage.

This test is only validated for dogs. A study to evaluate the concentration of D-dimers in healthy and sick cats, with and without DIC, concluded that the assay had limited value for diagnosis of DIC in this species (Tholen I et al).

| Coagulation Tests Learning Resources | |

|---|---|

Test your knowledge using flashcard type questions |

Equine Internal Medicine Q&A 03 |

Search for recent publications via CAB Abstract (CABI log in required) |

Coagulation Tests publications |

Links

References

- Fischbach, F T and Dunning, M B (2008) A manual of laboratory and diagnostic tests, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

- Hopper, K (2005) Interpreting coagulation tests. Proceedings of the 56th conference of La Società culturale italiana veterinari per animali da compagnia.

- Walker, K H et al (1990) Clinical Methods: The History, Physical and Laboratory Examinations (Third Edition), Butterworths.

- Cornell University Clinical Pathology Modules: Tests of Haemostasis - PIVKA

- Howard, M R and (2008) Haematology: an illustrated colour text, Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Mair, TS & Divers, TJ (1997) Self-Assessment Colour Review Equine Internal Medicine Manson Publishing Ltd

- NationWide Laboratories

| This article has been peer reviewed but is awaiting expert review. If you would like to help with this, please see more information about expert reviewing. |

Error in widget FBRecommend: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt6742038cf05712_65611520 Error in widget google+: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt6742038d06fcb6_53138731 Error in widget TwitterTweet: unable to write file /var/www/wikivet.net/extensions/Widgets/compiled_templates/wrt6742038d10f405_40784860

|

| WikiVet® Introduction - Help WikiVet - Report a Problem |